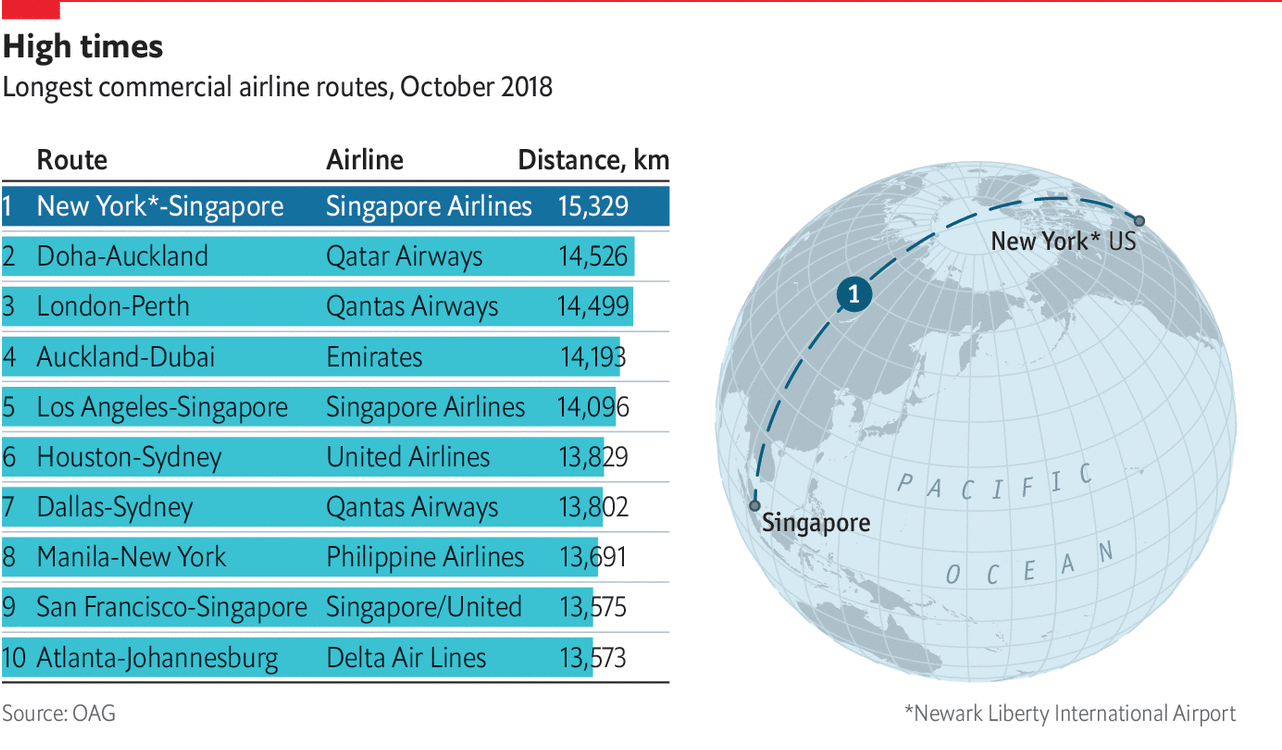

You might recall that back in March I wrote about the use of spherical maps to show great circles. This helps illustrate the actual routes that aircraft take in flight. (Yes, actual flight plans deviate based on routes, weather, traffic, &c.) At the time I wrote about how there was a soon-to-be Singapore–New York route. Ta da.

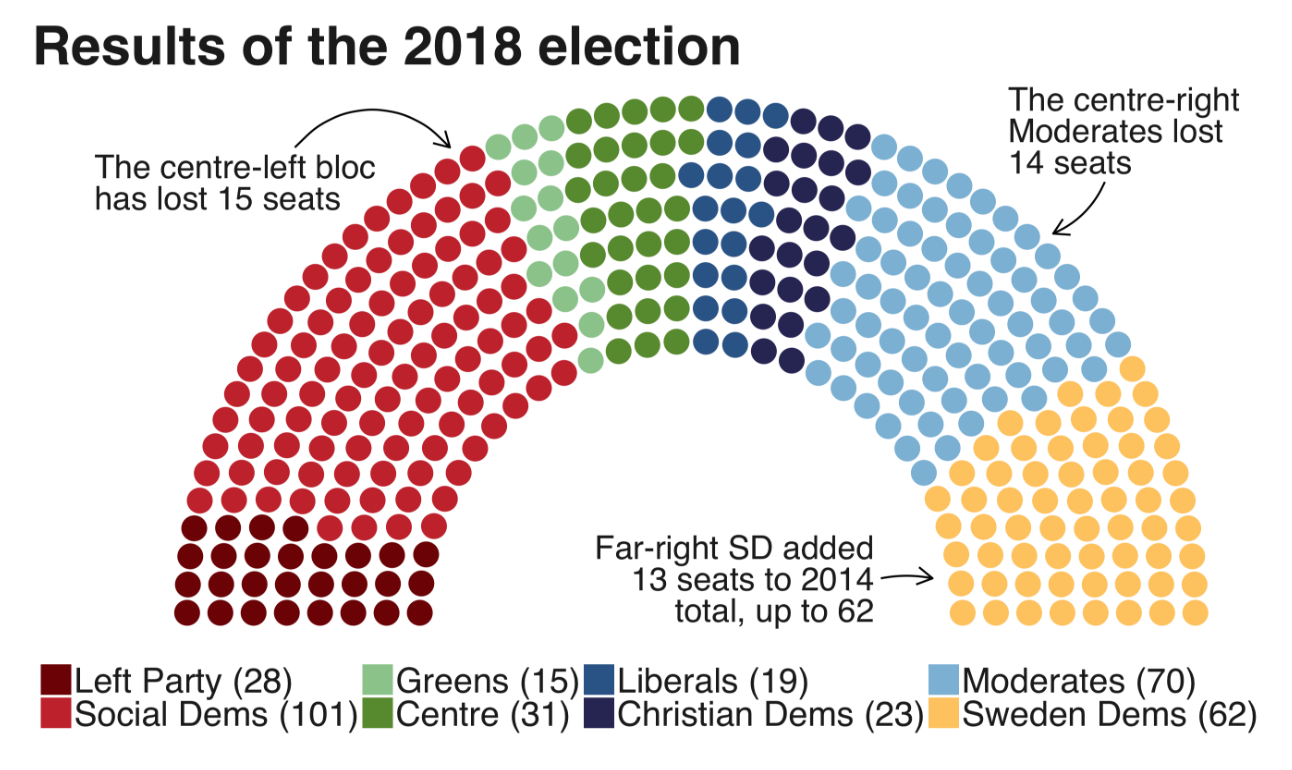

Nothing fancy here in this graphic from the Economist. It probably is just a reuse of the original but with the additional routes removed. But, I still love these kinds of maps. From a design manager standpoint, in a way this is great efficiency in that an element from a graphic made once can now, with minimal effort, be used in a second piece. And not in a meaningless, throw-in way, but this graphic does very much help to illustrate the actual route and long across the globe it travels.

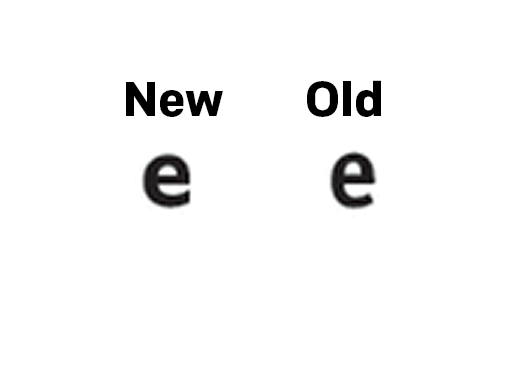

In a second note, not related to the graphic itself, I want to point out a subtle change made by the Economist. This is the first online graphic to use an updated chrome, which is the branding elements that surround the actual content of the piece.

The biggest change is a new or modified typeface for the graphic header. I have not seen anything about design changes at the Economist, but I will look into it. But the changes are, again, subtle. The best example in these two comparisons (new on the left, old on the right) is the shape of the letter e.

You can see how the terminal, or the part of the letter hooking and swinging out at the bottom, used to come to an end at an angle. Now it ends with a vertical chop. I haven’t looked too extensively at the typeface, but given the letter e, it appears to be a little bit wider of a face.

The other change, not quite as subtle, is the positioning of the iconic red rectangle around which so much of the Economist’s brand hangs. Bringing back the above graphic, you can see where I drew a black line to indicate the edge of the original graphic.

The box is now orientated horizontally (again, new is on the left), which actually brings it closer to the actual Economist logo. But, and probably more importantly, it allows the graphic’s edge to go to the, well, edge. And since their site uses generous whitespace around their graphics, they don’t necessarily need margins within the graphic.

They have also chosen to raise the level at which the header starts, i.e. there is less space between the red rule at the top of the graphic and the start of the words. This, however, appears to have been possible in the original design.

As more graphics roll out, I am going to be curious to see if there are other changes. Or even just to see how these subtle changes affect the rest of the graphics.

Credit for the piece goes to the Economist Data Team.