If you were unaware, in the wee hours of Friday, President Trump announced that he had tested positive for the coronavirus that causes Covid-19. It should be stated in the just three days hence, there is an enormous amount of confusion about the timeline as the White House is not commenting. From the prepared statement initially released it seems Trump first tested positive Wednesday. But that statement was then changed to fit the diagnosis in the wee hours of Friday morning. But just last night I saw reporting saying that test was actually a second, confirmatory test and the president first tested positive earlier Thursday.

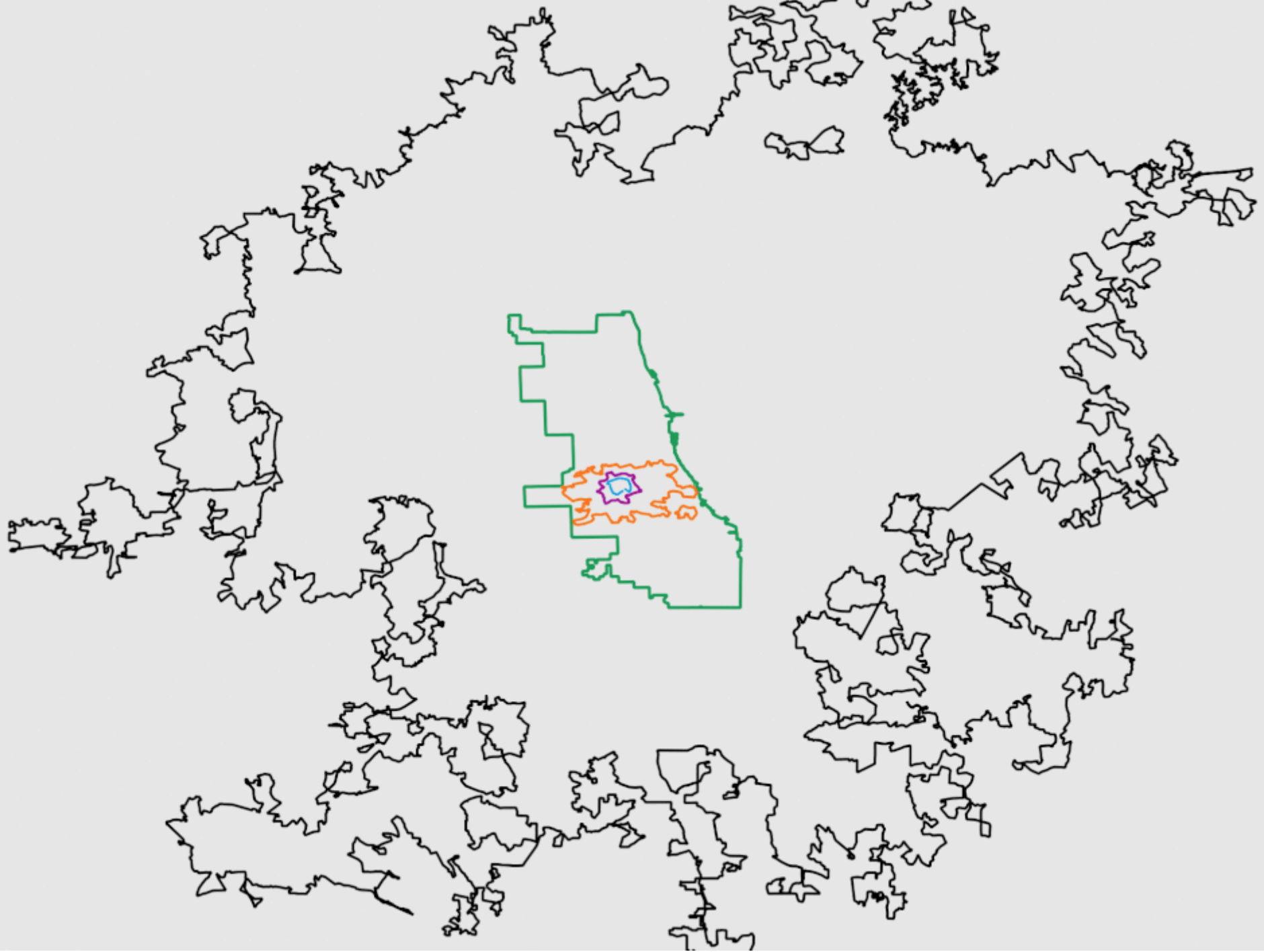

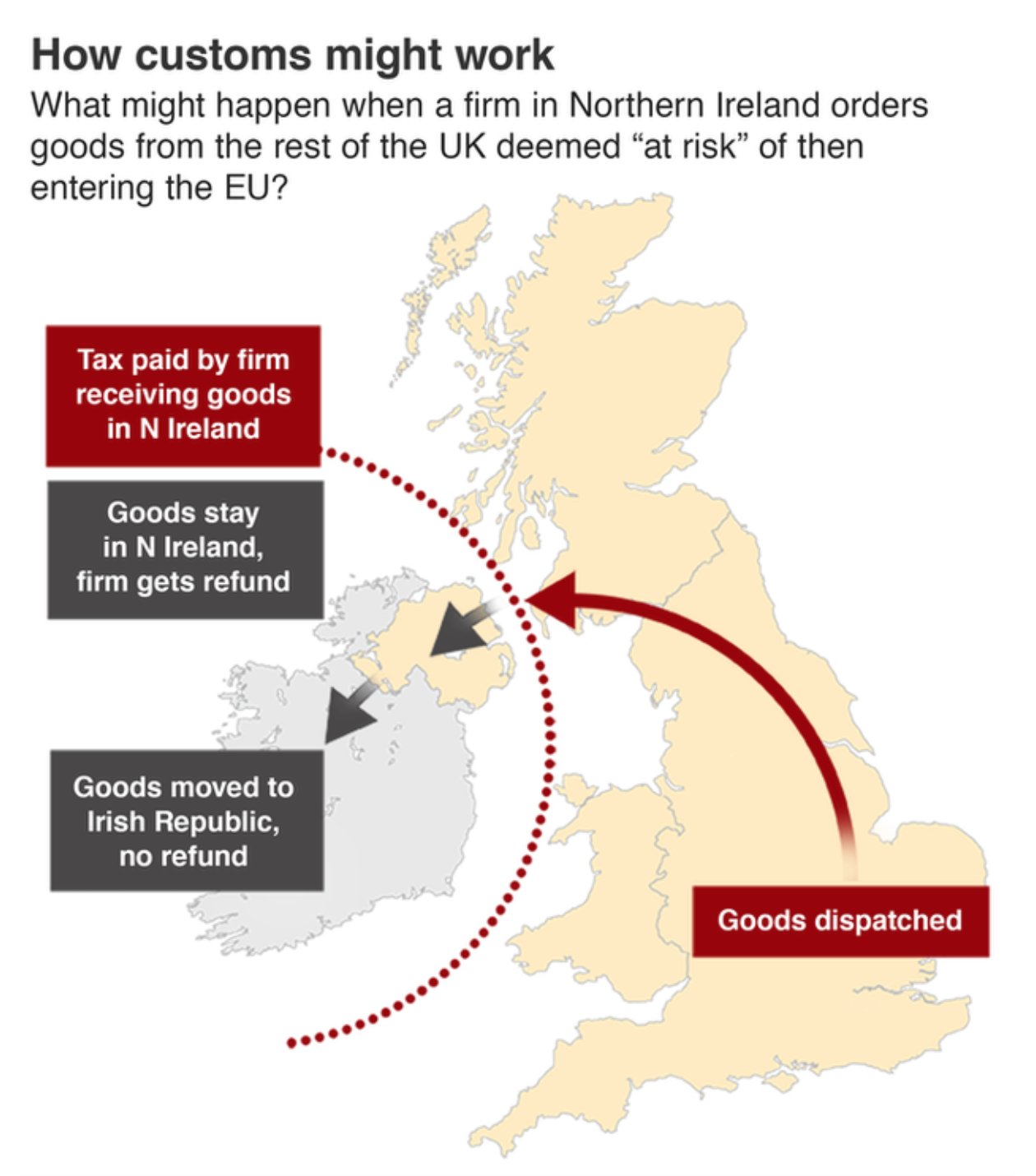

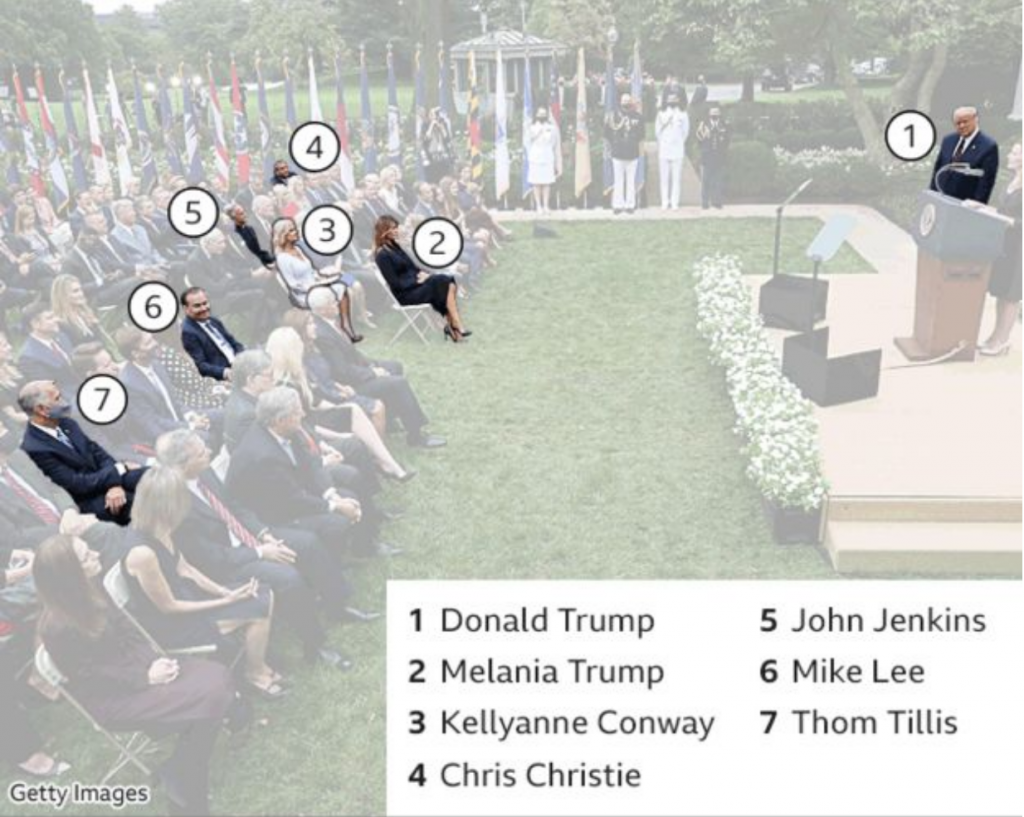

The timeline is also important because it would allow us to more definitively determine when the president was infected. The reporting indicates that he caught the virus at a Rose Garden ceremony at the White House to introduce his Supreme Court nominee, Amy Coney Barrett. This BBC graphic does a great job showing who from that ceremony has tested positive with the virus.

The photo also does a great job showing how the seven people there were situated. Six of the seven did not wear masks, only North Carolina Senator Thom Tillis did. There is no social distancing whatsoever. And not shown in this photo are the indoor pre- and post-ceremony festivities where people are in close quarters, mingling, talking, hugging, shaking hands, all also without masks.

It should be noted others not in the photograph, e.g. campaign manager Bill Stepien, communications advisor Hope Hicks, and body man Nicholas Luna, have also now been confirmed positive.

The final point is that this goes to show how much the administration does not take the pandemic seriously. Right now the Covid data for some states indicates that the virus is beginning to spread once again. And so maybe this serves as a good reminder to the general public.

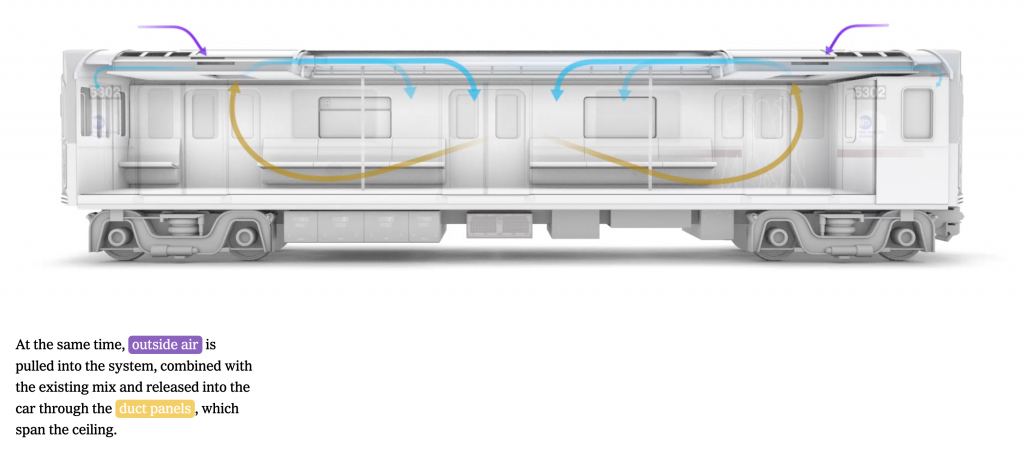

Just because you are socialising outdoors does not make you safe. Outdoors is better than indoors. No gatherings is better than small gatherings is better than large, well attended garden parties. Masks are better than no masks. Rapid result test screening is better than no test screening. Temperature checks are better than no temperature checks.

But the White House only did that last one, temperature checks, in order to protect the president before admitting people to the Rose Garden. Compare that to how they protect the president from other physical threats. He has Secret Service agents standing near him (or riding with him in hermetically sealed SUVs for joyrides whilst he is infected and contagious); he has checkpoints and armed fences further out to secure the perimeter. Scouts and snipers are on the White House roof for longer range threats. And there is a command centre coordinating this with I presume CCTV and aerial surveillance to monitor things even further out. In short, a multi-layered defence keeps the president safe.

If you just take temperatures; if you just hang out outside; if you just wear masks; if you just do one of those things without doing the others I mentioned above, you are putting yourself—and through both pre-diagnostic/pre-symptomatic and asymptomatic spreading, others—at risk.

But on Sunday night, Trump campaign strategist went on television said that now that President Trump has been infected, been hospitalised, he is ready to lead the fight on coronavirus. Great. We need leadership.

But where was that leadership seven months ago when your advisors told you in January about the impact this pandemic would likely have on the United States? Where was the leadership in February saying the coverage was a hoax? Where was it in March when he said the virus would go away in April with the warmer weather? Where was it in April when it didn’t go away, when things continued to get worse? Where was it in May when thousands of Americans were dying? Where was it in June when states began to reopen even though the virus was still out-of-control and testing and contact tracing was less available than necessary to contain outbreaks? Where was it in July? And August? And September? Where was the leadership at a Rose Garden party celebrating the nomination of a Supreme Court justice, a party where at least seven people have been infected and one of them, the president of the United States, has been hospitalised with moderate to severe symptoms?

Credit for the piece goes to the BBC.