Baseball season begins next week. For different teams it starts different days, but for the Red Sox at least, pitchers and catchers report to Spring Training on Tuesday. But the Red Sox, along with many other teams throughout baseball, have holes in their roster. Why? Arguably because nearly 100 free agents remain unsigned.

I do not intend to go into the different theories as to why, but this has been a remarkably slow offseason. How do we know? Well using MLB Trade Rumours listing of the top-50 free agents this year, and the signings reported on Baseball Reference, we can look at the upper and middle, or maybe upper-middle, tiers of free agency.

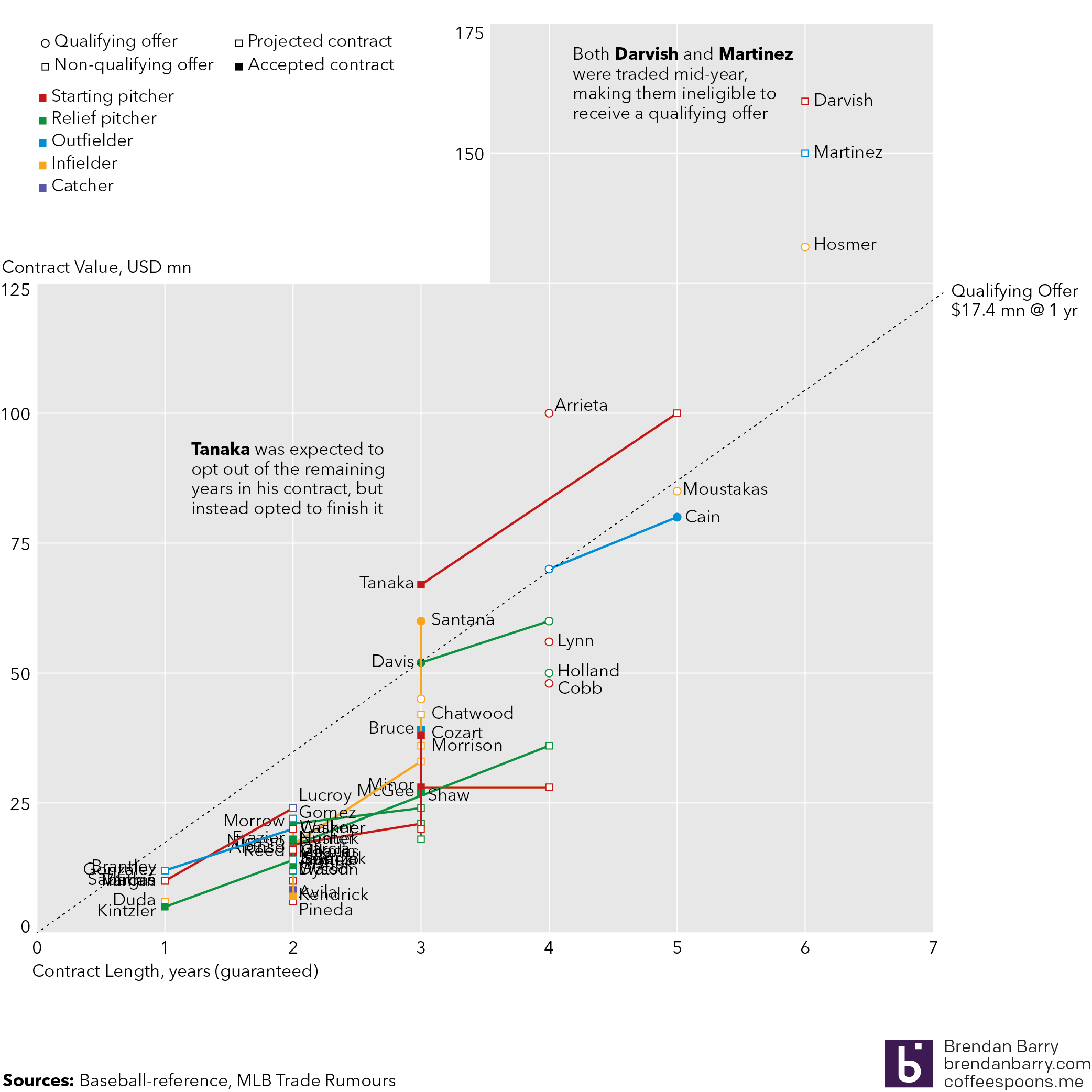

Kind of messy to look at with all the player labels, but we can see here the projected contracts, in both length and total value, along with the contracts players signed, if they have. And for context we can see how those contracts compares to the Qualifying Offer (QO). What’s that? Complicated baseball stuff that is meant to ensure teams that lose stars or highly valuable players are compensated, especially since they might come from smaller market teams that cannot afford superstar prices. The QO is meant to help competitiveness in the sport. How does it do that? Let’s just say complicated baseball stuff. We should also point out that some players, most notably the Yankees’ Masahiro Tanaka, were expected to opt out of their contracts and try the free market. Tanaka did not, which is why his projection was so far off.

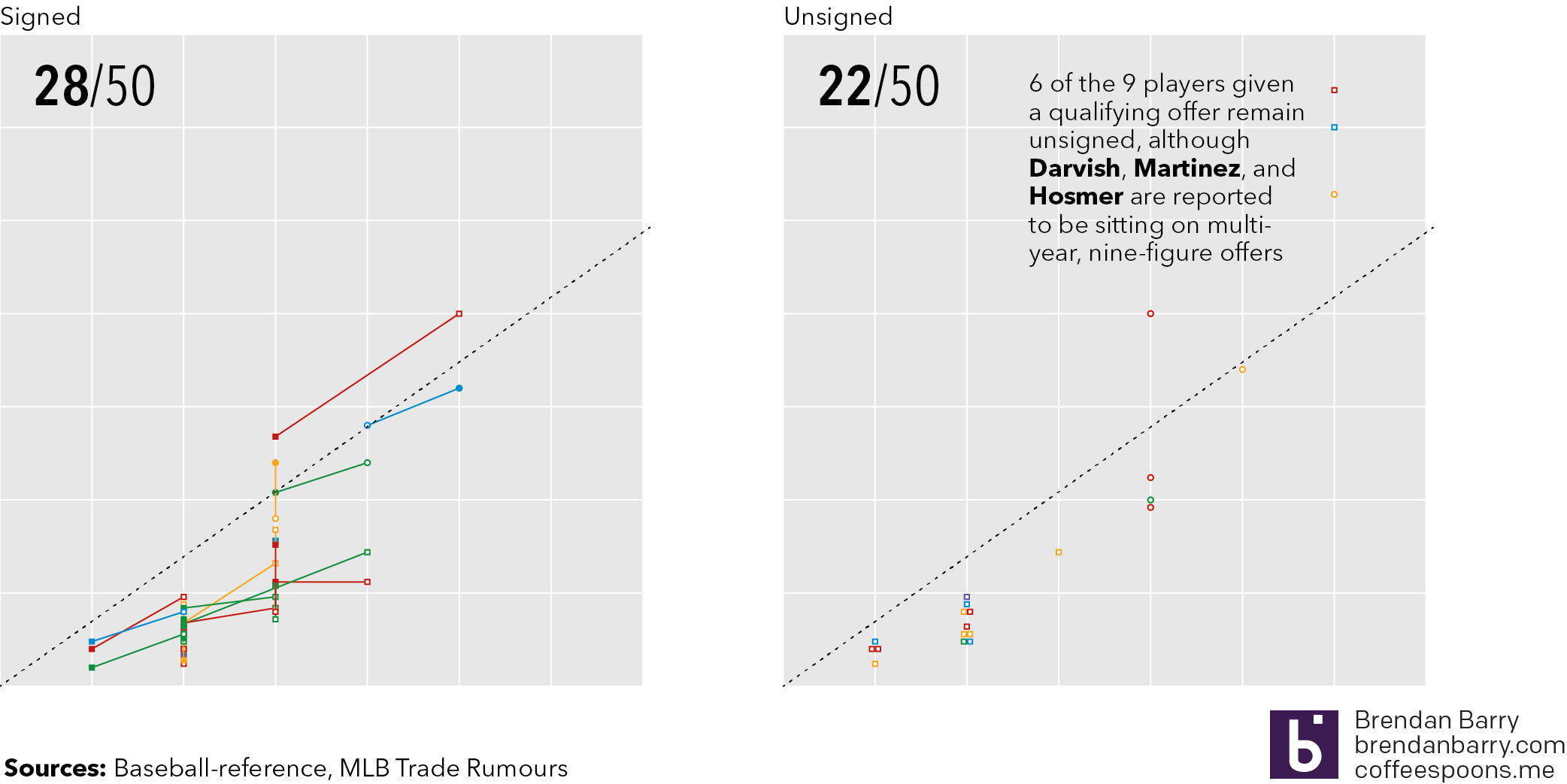

So is it true that free agency is or has moved slowly? Consider that approximately 100 free agents remain unsigned as of late Thursday night—please no big signings tomorrow morning—and that of the top 50, 22 of them remain unsigned. And if we take the QO as a proxy for the best players in the game, add in two players who were exempt because baseball stuff, we can say that 8 of the 11 best players remain unsigned. Though, in fairness to ownership, three of those players are reportedly sitting on multi-year offers in the nine-figure range.

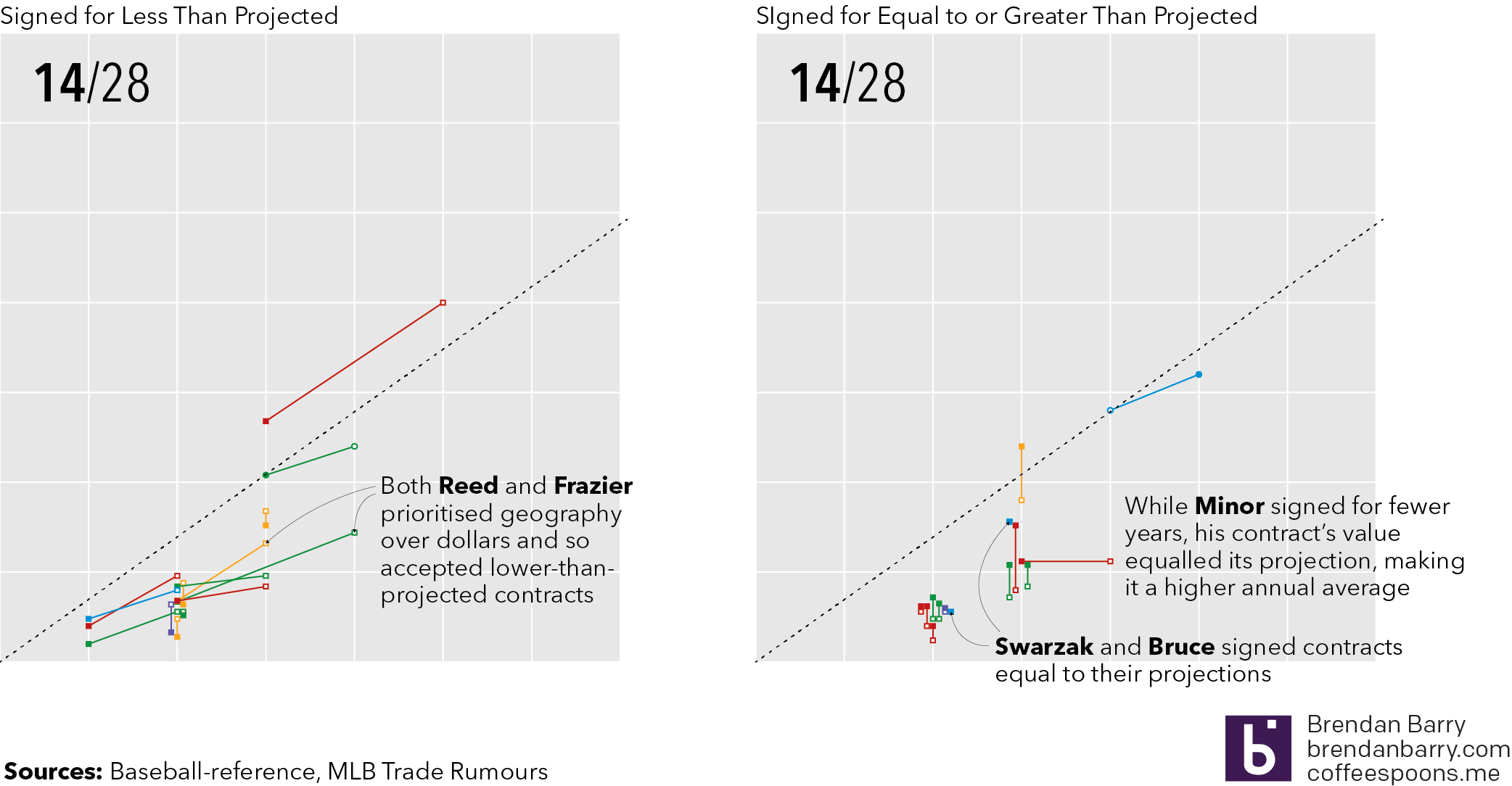

But if players are unsigned, does that mean they are competing for lower value contracts? Possibly. If we use MLB Trade Rumours’ projected contracts, because in years past they have proven smart at these things, we can see that for the 28 who have signed, it’s a roughly even split in terms of the number of players who have signed for more or less than their projection. Sometimes however, non-monetary factors come into play. Two notable free agents, Todd Frazier and Addison Reed, both reportedly signed lesser value contracts to play closer to a specified geography, in Frazier’s case the Northeast and in Reed’s the Midwest.

But the telling part in that graphic is not necessarily the vertical movement, i.e. dollars, but the horizontal movement. (Though we should call out the cases of Carlos Santana and Tyler Chatwood, signed by the Phillies and Cubs respectively, who did far better than projected.) Consider that a team might not have a lot of money to spend and so might extend a contract over additional years, offering job security to a player. Or in a bidding war, the length of the contract might be what leads a player to pick one team over another. In those cases we would expect to see more left-to-right movement. So far we have only had one player, Lorenzo Cain, who signed for more years than expected. Most players who have signed for less have also signed for fewer years. Note the cluster of right-to-left, or shorter-than-expected, contracts in the lower tiers versus the small, vertical-only cluster in the same section for those signing greater than projected contracts.

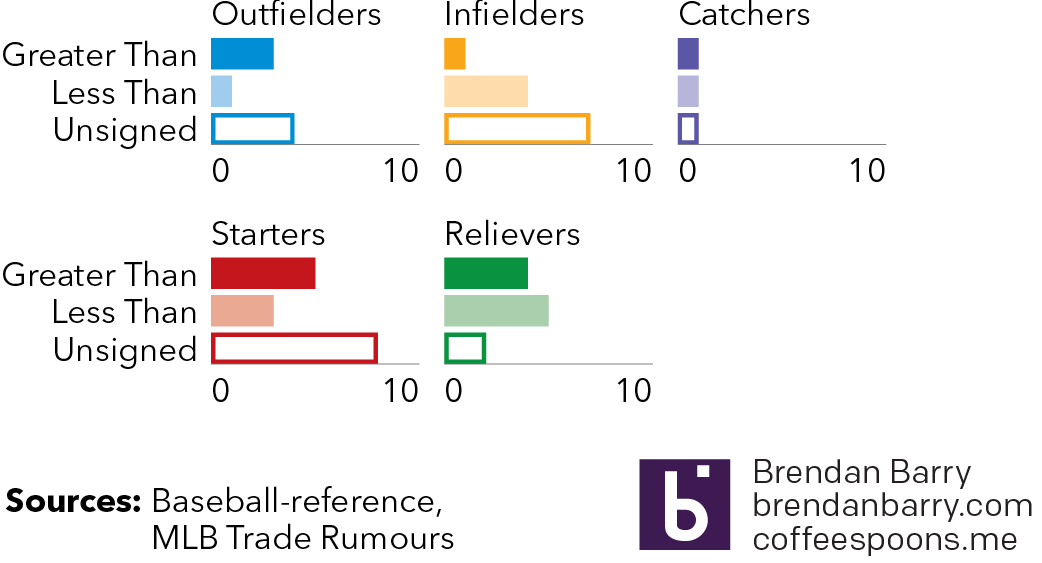

Lastly, are these trends hitting any specific positional type of player? Well maybe. Ignoring the market for catchers because of how small the pool was—though the case of Jonathan Lucroy as the unsigned catcher is fascinating—we can see that the market has really been there for relief pitchers as there are few of the top-50 remaining on the market. Starting pitchers and outfields, while with quite a few still on the market, have generally done better than projected. But infielders lag behind with numerous players unsigned and those that have signed, most have signed for less than projected.

But at the same time, I would fully expect that once these higher level free agents come off the board—while one would think they would certainly be signed, who knows in such a weird offseason as this—the unsigned middle and lower tiers will quickly follow suit.

Of course none of this touches upon age. (Largely because lack of time on my part.) Though, in most cases, getting to free agency in and of itself makes a player older by definition the way baseball’s pre-arbitration and arbitration salary periods work. (Again, more baseball stuff but suffice it to say your first several years you play for peanuts and crackerjacks.)

Hopefully by this afternoon—Friday that is—some of these players will have signed. After all, baseball starts next week. If we are lucky this post will be outdated, at least in terms of the dataset, come Monday. Regardless, it has been a fascinating albeit boring baseball offseason.

Credit for the data goes to MLB Trade Rumours and Baseball Reference.