In 1628, Sweden launched one of its largest and most powerful warships not just in Sweden, but in all of Europe. She was to participate in the wars with Poland and Lithuania as Sweden sought to expand her growing empire. After two years of construction in Stockholm’s naval yard she set sail into a calm day with a light breeze.

After a strong gust pushed her hard to port, she righted herself and continued to set sail to a fortress to load 300 troops for the war. But only 20 minutes into her maiden voyage, a second gust of wind pushed her again hard to port so much so that water began to flood in via her open lower gunports. As the continued to rush in, she never righted herself and sank, not to be recovered for 300 years.

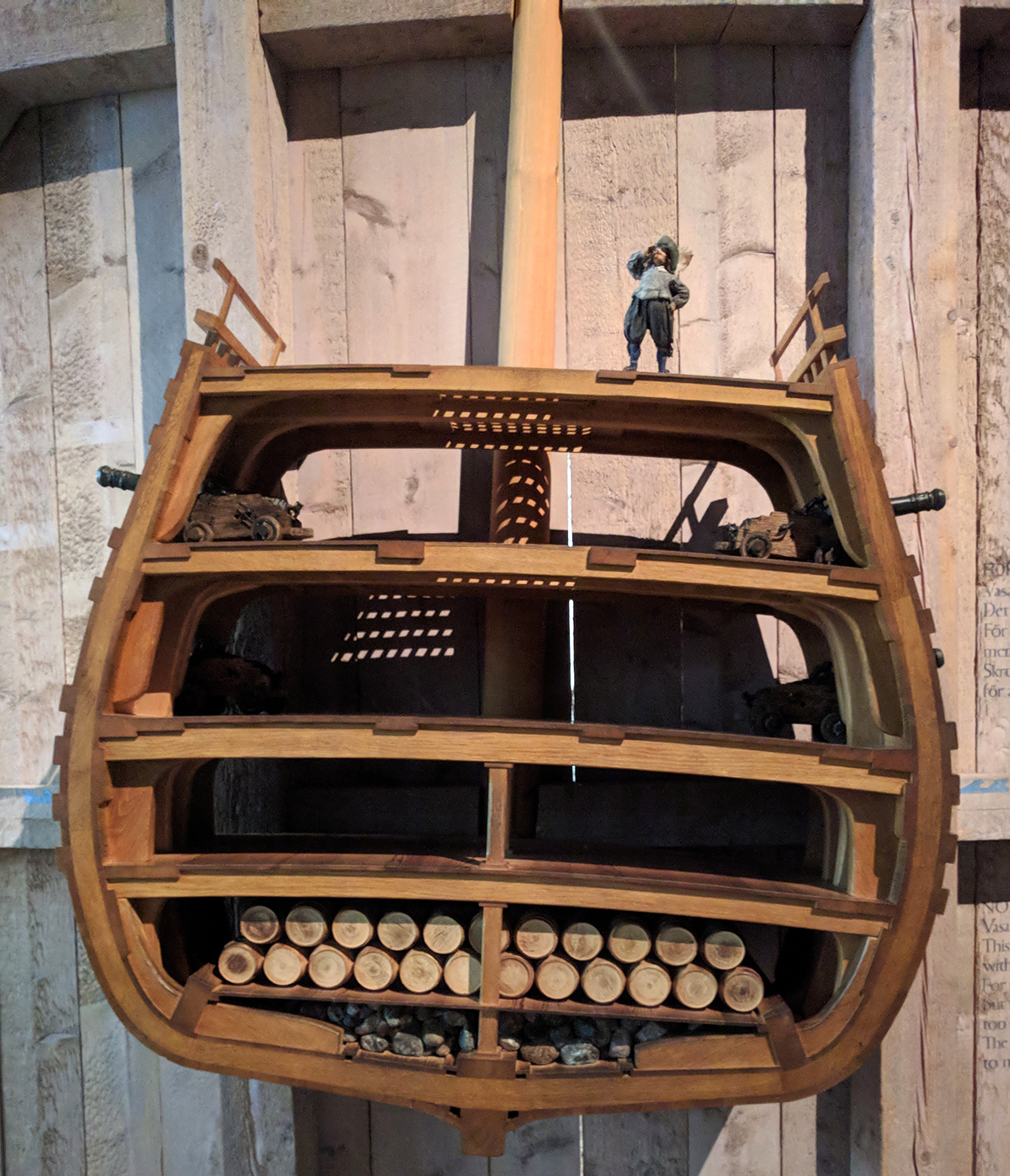

The recovery itself is a great story, but the question was why did she sink? This model in the large Vasa museum, built to host the recovered and preserved ship, shows just how dangerously she was designed. Take careful note of the faint blue waves signifying the waterline of the ship and how close they are to the lower gunports.

The short takeaway is that the ship was top-heavy and she needed to be both wider and deeper to support her displacement. I like the model here, but my one complaint with it is the waterline. Even when I was standing in front of it, I did not notice the waves at first. A little bit more emphasis or paint, perhaps to show the water beneath the ship, would really help to convey just how little of the ship was below the waterline.

Credit for the piece goes to the Vasa Museum design staff.