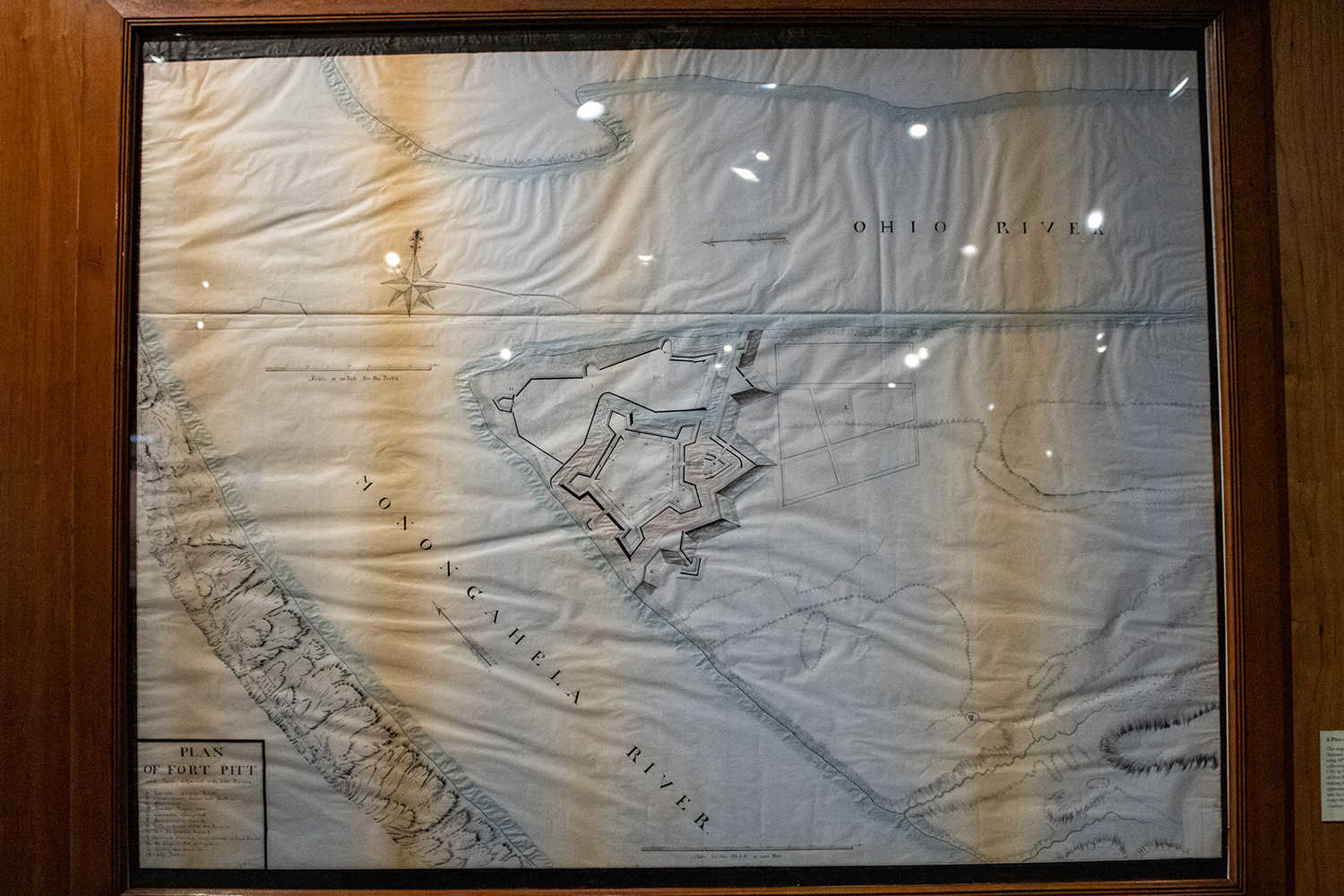

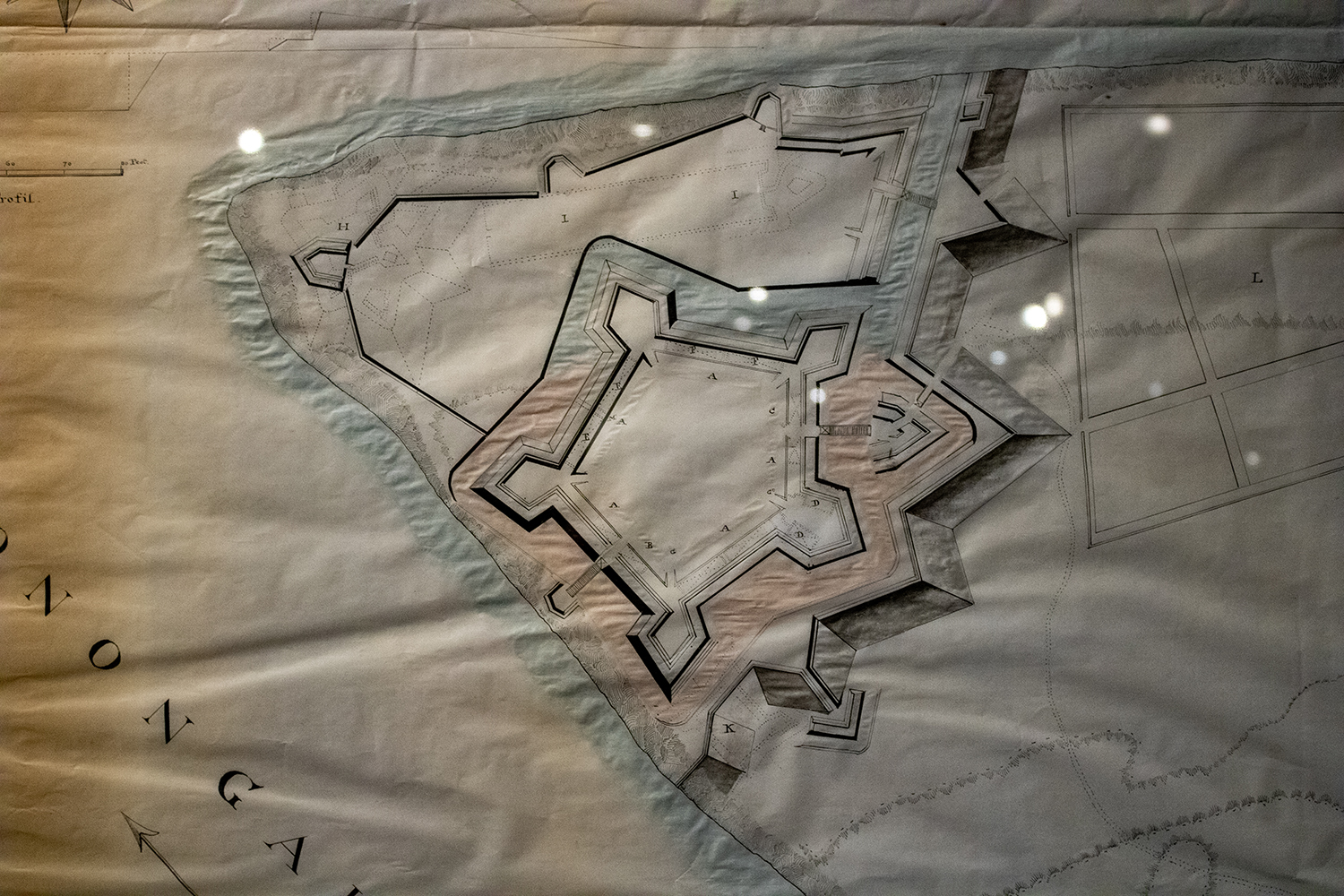

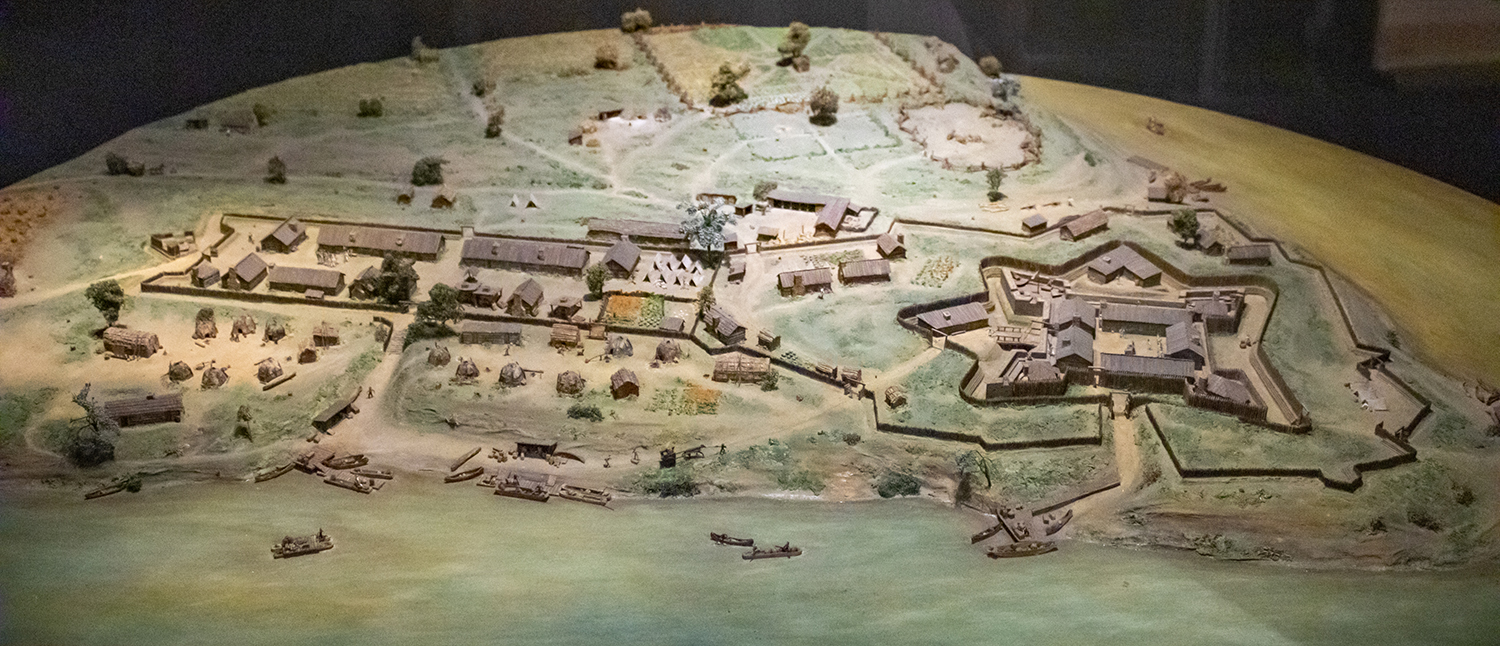

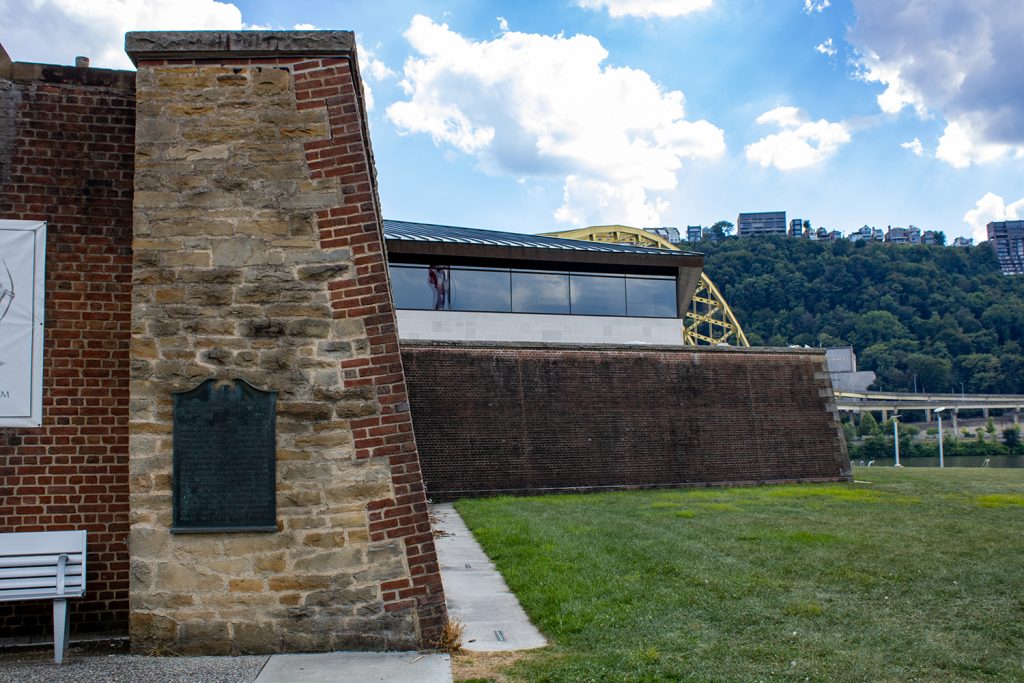

For the last two days I have been writing about the Fort Pitt Museum and some infographics, environmental graphics, diagrams, and dioramas that help explain the strategic value and thus history behind the peninsula at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers. In particular, we looked at Fort Duquesne, the French attempt to fortify the position, and then Fort Pitt, the far more successful British attempt.

But a fortress without weaponry is like a snapping turtle without a sharpened beak. And once the fortifications were built, the British began moving in artillery pieces and hundreds of soldiers to defend their claim on the land. Local Native American tribes invited the British in and to station soldiers, but relations soured after a few years when it became clear the British, unlike the French, were more interested in settling the land.

In 1763, Native American discontent coalesced around Pontiac, an Ottawa warrior chief, who directed the outrage into violent actions in the western colonial lands. Pontiac’s War had begun. The British, recently victorious over the French, suffered several defeats as Native American forces took several British forts and raided settlements killing unknown numbers of settlers.

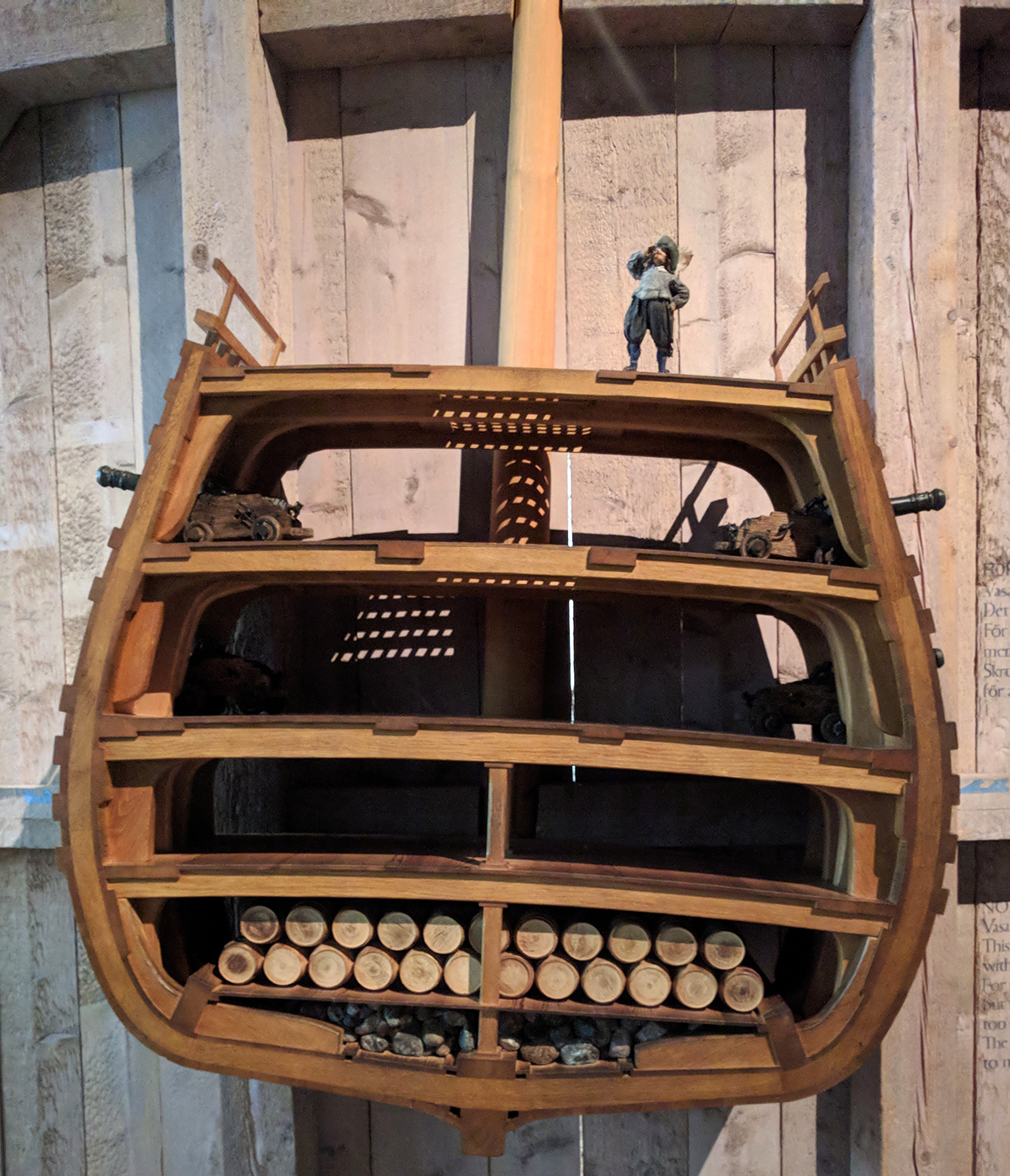

At the forks of the Ohio, local Native Americans besieged Fort Pitt. For two months, Fort Pitt was cut off from resupply and local settlers, who had poured into the fort, even took up arms. But the biggest weapons the British had were the artillery at the fortress.

Though it should be noted this was the incident during which a small smallpox outbreak occurred amongst the settlers and British military forces used smallpox infected blankets as gifts to the Native Americans. In later letters, this tactic was commended by senior British military officials. However, the efficacy of the action from a military perspective is debatable at best.

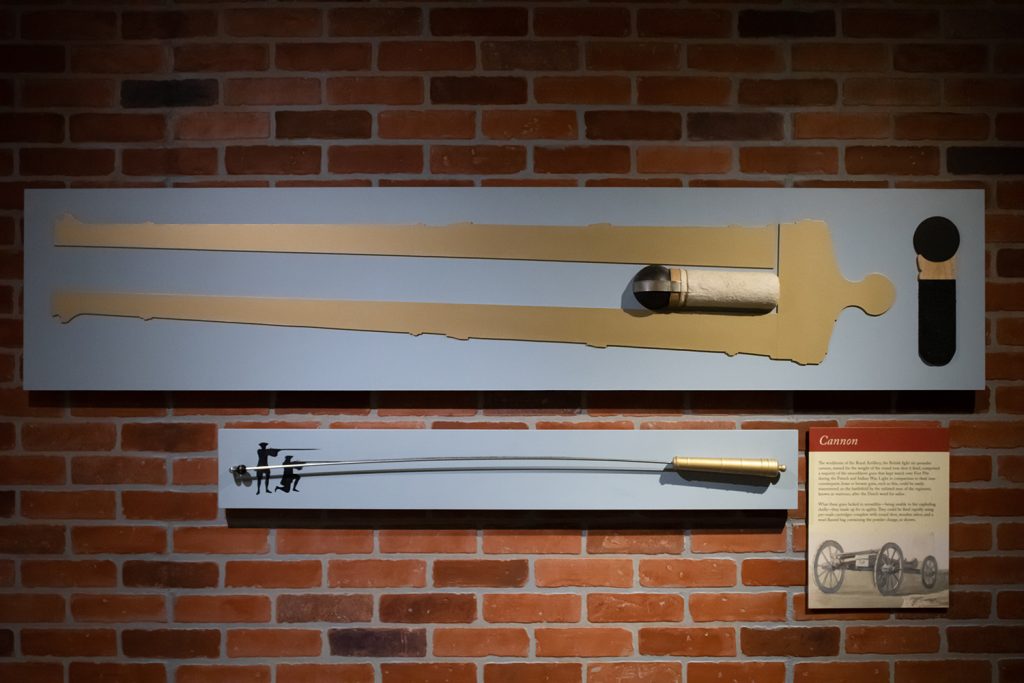

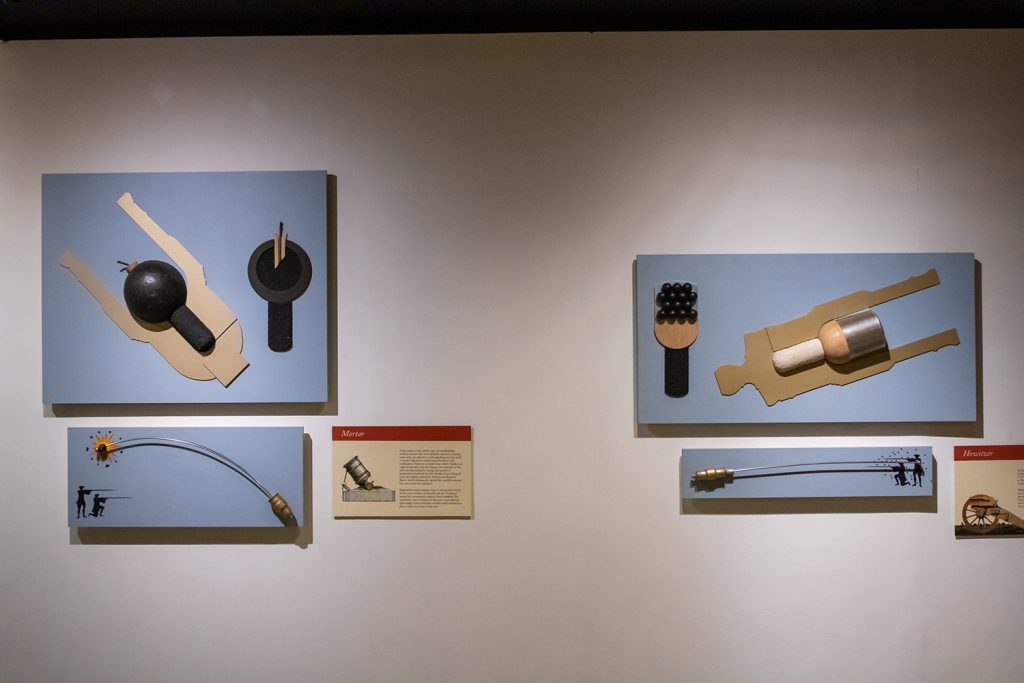

The British had three main types of artillery at their disposal: cannon, howitzers, and mortars. And if you have no idea what the differences are, no worries, because the Fort Pitt Museum has several great graphics explaining their differences and the pros and cons to each.

Above we have a diagram of a cannon. At the time cannon differentiated themselves by being relatively easier to construct and maintain. They fired solid, non-explosive projectiles at relatively flat trajectories. If you ever saw the Patriot with Mel Gibson, the scene where a gun fires a ball that then bounces through ranks of infantry and severs numerous legs, most likely that was a cannon.

The remaining two types were used for launching projectiles at higher angles, almost lobbing them up and over fortifications or enemy troop formations. Howitzers were the longer-ranged of the two and whilst broadly similar to cannon, at the time they differentiated themselves by being able to fire explosive projectiles. In other words, instead of a solid ball of iron as described above, this could explode and send shrapnel down on a larger area of massed infantry.

The mortar, in that sense, is similar to the howitzer. It could send explosive shells above troops and fortifications, but it was designed to do so at high-angles. This was particularly important in counter-siege warfare when the British defenders needed ways to fire at Native American soldiers who closely approached Fort Pitt’s defensive walls.

The graphics do a great job showing just how these three types of artillery were different and could be used to different effects. The graphics don’t do too much and don’t use elaborate illustrations. They are very effective and very efficient. Well done.

Credit for the pieces goes to the Fort Pitt Museum design staff.