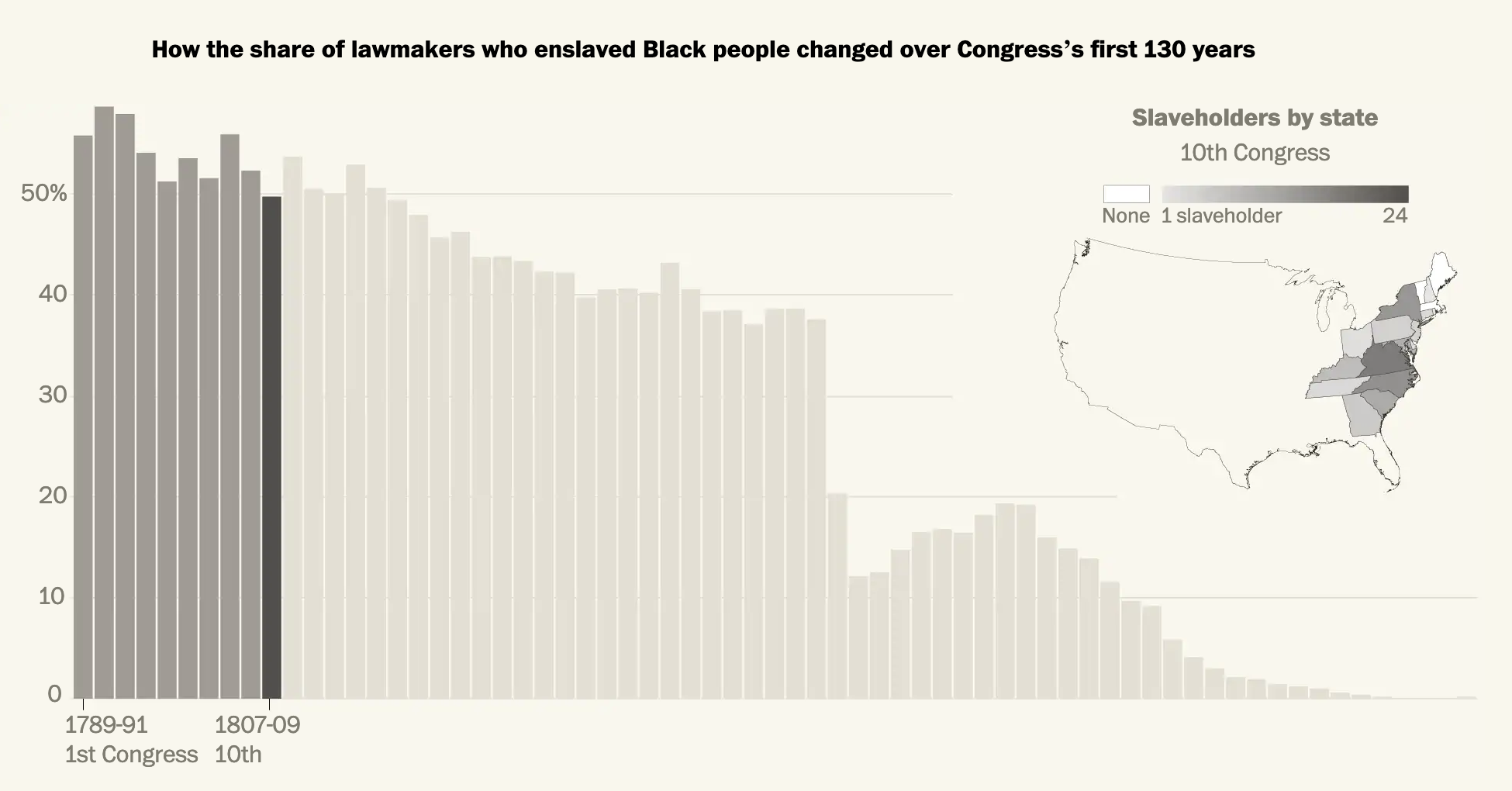

Taking a break from going through the old articles and things I’ve saved, let’s turn to a an article from the Washington Post published earlier this week. As the title indicates, the Post’s article explores slaveholders in Congress. Many of us know that the vast majority of antebellum presidents at one point or another owned slaves. (Washington and Jefferson being the two most commonly cited in recent years.) But what about the other branches of government?

The article is a fascinating read about the prevalence of slaveholders in the legislative branch. For our purposes it uses a series of bar charts and maps to illustrate its point. Now, the piece isn’t truly interactive as it’s more of the scrolling narrative, but at several points in American history the article pauses to show the number of slaveholders in office during a particular Congress. The screenshot below is from the 1807 Congress.

That year is an interesting choice, not mentioned explicitly in the article, because the United States Constitution prohibited Congress from passing limits on the slave trade prior to 1808. But in 1807 Congress passed a law that banned the slave trade from 1 January 1808, the first day legally permitted by the Constitution.

Graphic-wise, we have a set of bar charts representing the percentage and then a choropleth map showing each state’s number of slaveholders in Congress. As we will see in a moment, the map here is a bit too small to work. Can you really see Delaware, Rhode Island, and (to a lesser extent) New Jersey? Additionally, because of the continuous gradient it can be difficult to distinguish just how many slaveholders were present in each state. I wonder if a series of bins would have been more effective.

The decision to use actual numbers intrigues me as well. Ohio, for example, has few slaveholders in Congress based upon the map. But as a newly organised state, Ohio had only two senators and one congressman. That’s a small actual, but 33% of its congressional delegation.

Overall though, the general pervasiveness of slaveholders warrants the use of a map to show geographic distribution was not limited to just the south.

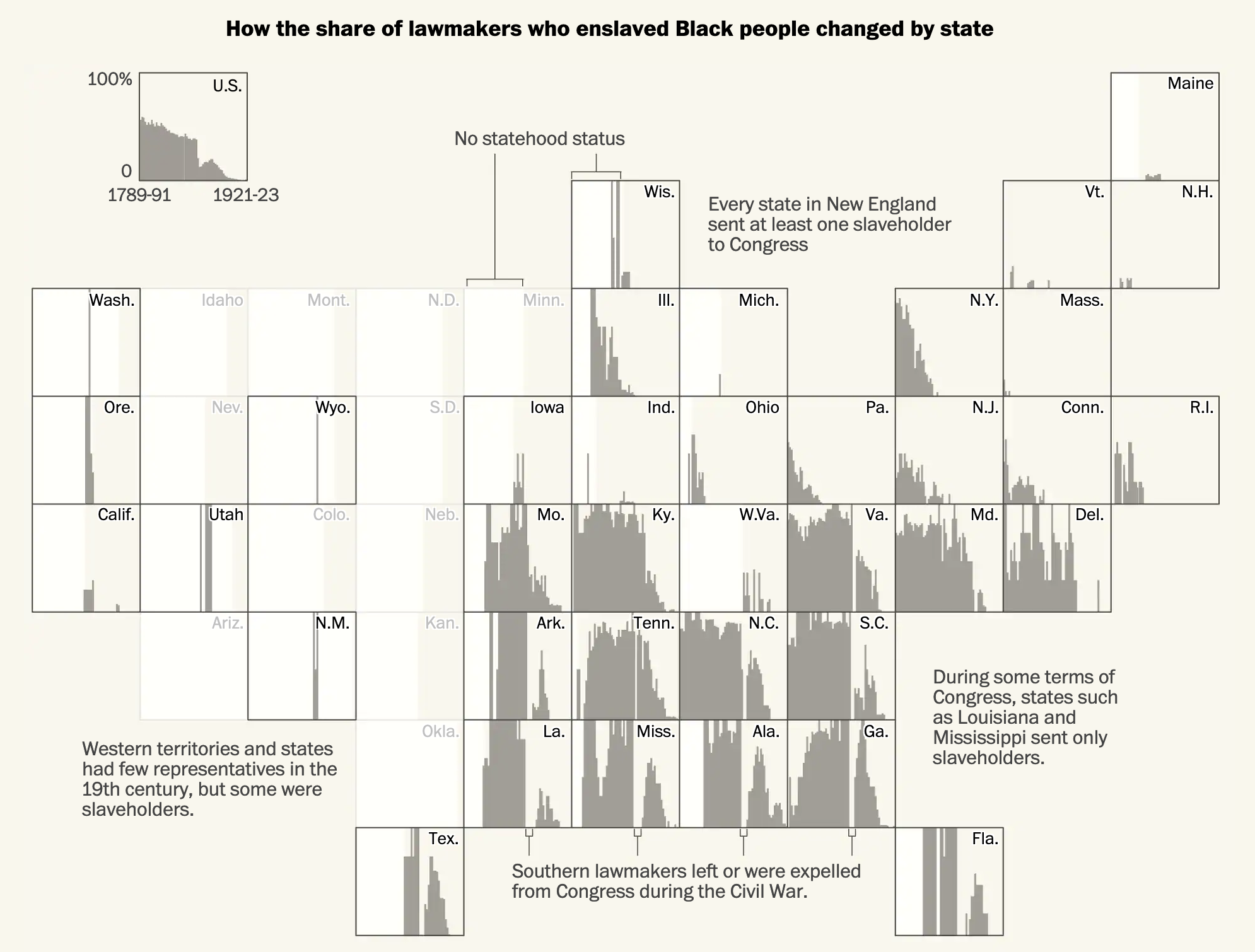

Later on we have what I think is the best graphic of the article, a box map showing each state’s slaveholders over time.

Within each state we can see the general trend, including the legacy of the Civil War and Reconstruction. The use of a light background allows white to represent pre-statehood periods for each state. And of course some states, notably Alaska and Hawaii, joined the United States well after this period.

But I also want to address one potential issue with the methodology of the article. One that it does briefly address, albeit tangentially. This data set looks at all people who at one point or another in their life held slaves. First, contextually, in the early years of the republic slavery was not uncommon throughout the world. Though by the aforementioned year of 1807 the institution appeared on its way out in the West. Sadly the cotton gin revolutionised the South’s cotton industry and reinvigorated the economic impetus for slavery. There after slavery boomed. The banning of the slave trade shortly thereafter introduced scarcity into the slave market and then the South’s “peculiar institution” truly took root. That cotton boom may well explain how the initial decline in the prevalence of slaveholders in the first few Congresses reversed itself and then held steady through the early decades of the 19th century.

And that initial decline before a hardening of support for slavery is what I want to address. The data here looks only at people who at one point in their life held slaves. It’s not an accurate representation of current slaveholders in Congress at the time they served. It’s a subtle but important distinction. The most obvious result of this is how after the 1860s the graphics show members of Congress as slaveholders when this was not the case. They had in the past held slaves.

That is not to say that some of those members were reluctant and, in all likelihood, would have preferred to have kept their slaves. And therefore those numbers are important to understand. But it undermines the count of people who eventually came to realise the error of their ways. The article addresses this briefly, recounting several anecdotes of people who later in life became abolitionists. I wonder though whether these people should count in this graphic as—so far as we can tell—their personal views changed so substantially to be hardened against slavery.

I would be very curious to see these charts remade with a data set that accounts for contemporary ownership of slaves represented in Congress.

Regardless of the methodology issue, this is still a fascinating and important read.

Credit for the piece goes to Adrian Blanco, Leo Dominguez, and Julie Zuazmer Weil.