It is Monday, so it must be another Brexit vote day. And today we have Indicative Vote Day 2. If you recall from last week, the House of Commons wrestled control over parliamentary business away from the government and created a two-step process to try and see if any alternative to Theresa May’s Brexit plan can receive a workable, sustainable majority in the House.

The first step went about as well as could be expected. Nothing received a majority, but a customs union and a confirmatory vote by the public on the final deal both came very close to a majority: 8 and 27 votes, respectively. Likely, the vote today will be on those options.

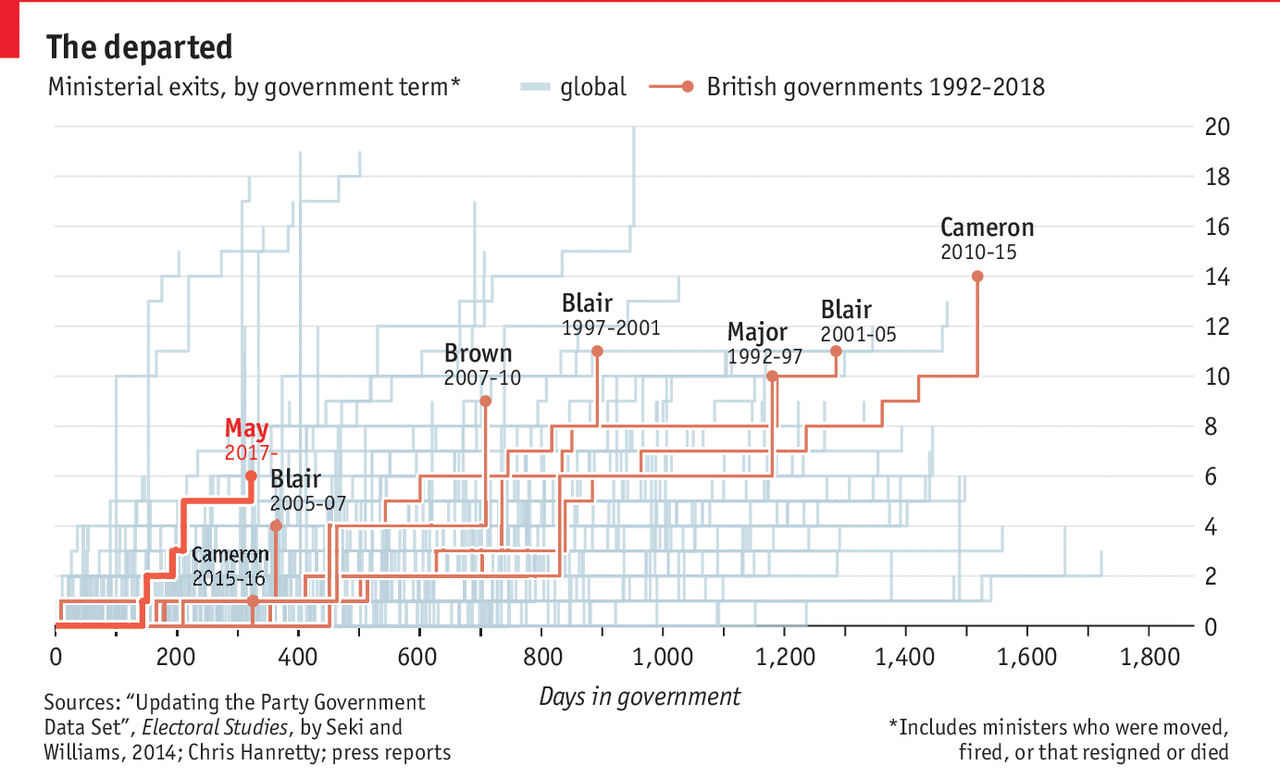

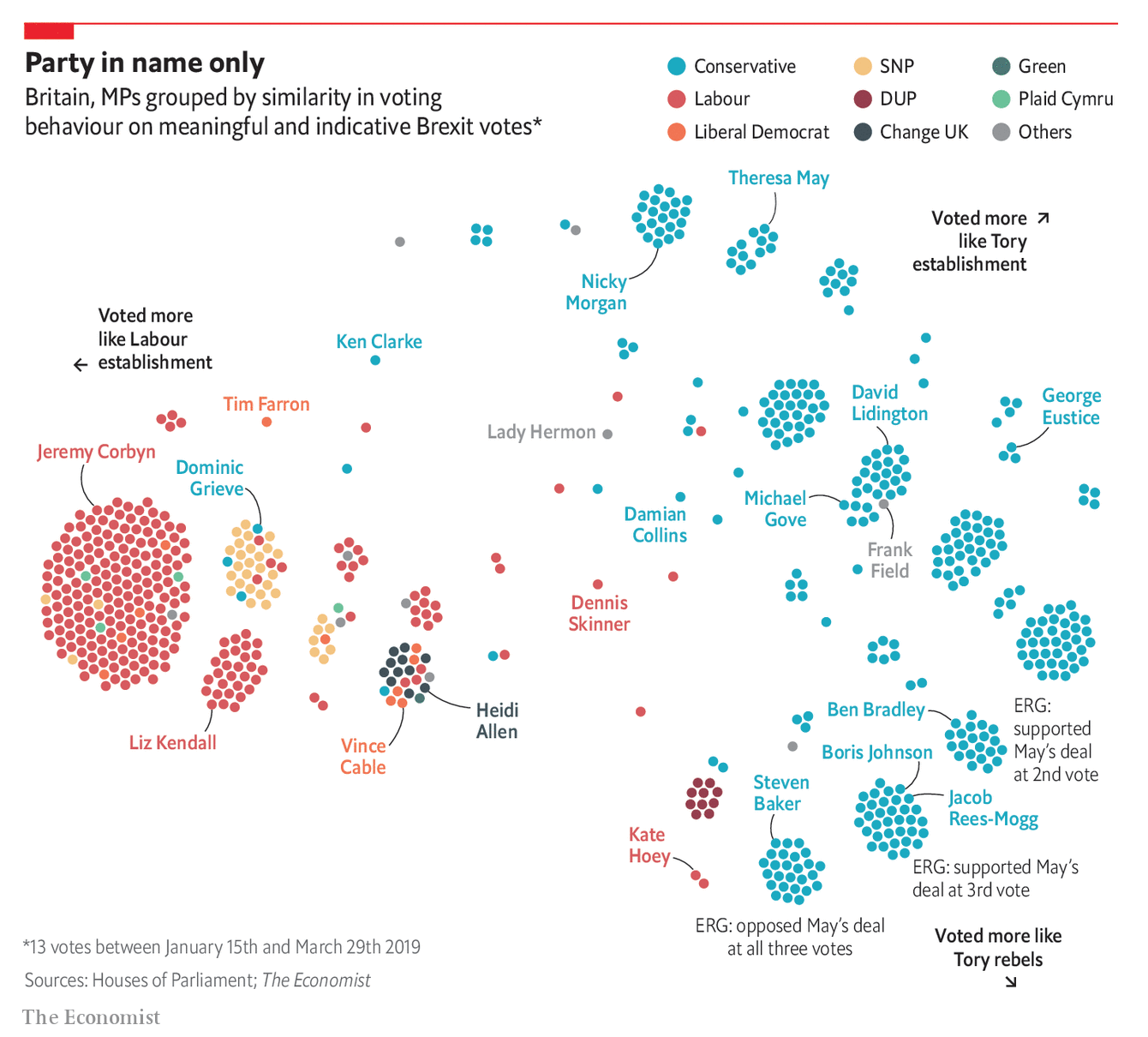

But one reason for this lack of majority is that the idea of Europe has always fractured the Conservative Party. And in a recent piece by the Economist, we can see just how fractured the Tories have become.

Maybe a little bit counterintuitively, this plot does not look at an MP’s opinion on Brexit, but just with whom they are more likely to vote. The clearest takeaway is that whilst Labour remains relatively united, the Tories are in a small little divisions across the field.

In terms of design, there is not much to comment upon. It is not a scatter plot in terms of the placement of the dots does not refer to Brexit opinions, as I mentioned. It is more about the groupings of MPs. And in that sense, this does its job.

Credit for the piece goes to the Economist Data Team.