Or just shake my hand, because today marks the second St. Patrick’s Day spent in isolation. I am lucky, of course, because two years ago I spent the holiday in Dublin. One of those bucket list kind of things. There I ran into a(n American) friend who was coincidentally in town. Then the next day I took the train to Cork to visit another friend. If you don’t count weddings, I think that was the last big trip I took.

Two years hence, I am here in my flat alone on a holiday meant to be spent with family and friends. But in the last year, I made significant progress on my Irish genealogy. For part of that progress I took two additional DNA tests. So this St. Patrick’s Day seems like a good time to reflect on those tests.

For those that don’t know, I do a lot of genealogy work as a hobby. Primarily I focus on paper records, but DNA is an important piece of the puzzle. In a sense, it is the only record that cannot lie. It will reveal your biological connections to family that may have been otherwise lost. And it cannot be faked.

But that’s only true for your genetic matches. Those are the real power of taking a DNA test. I would bet, however, that most people initially take the tests for the ethnicity estimates. On a day like today, how Irish are you? How Irish am I?

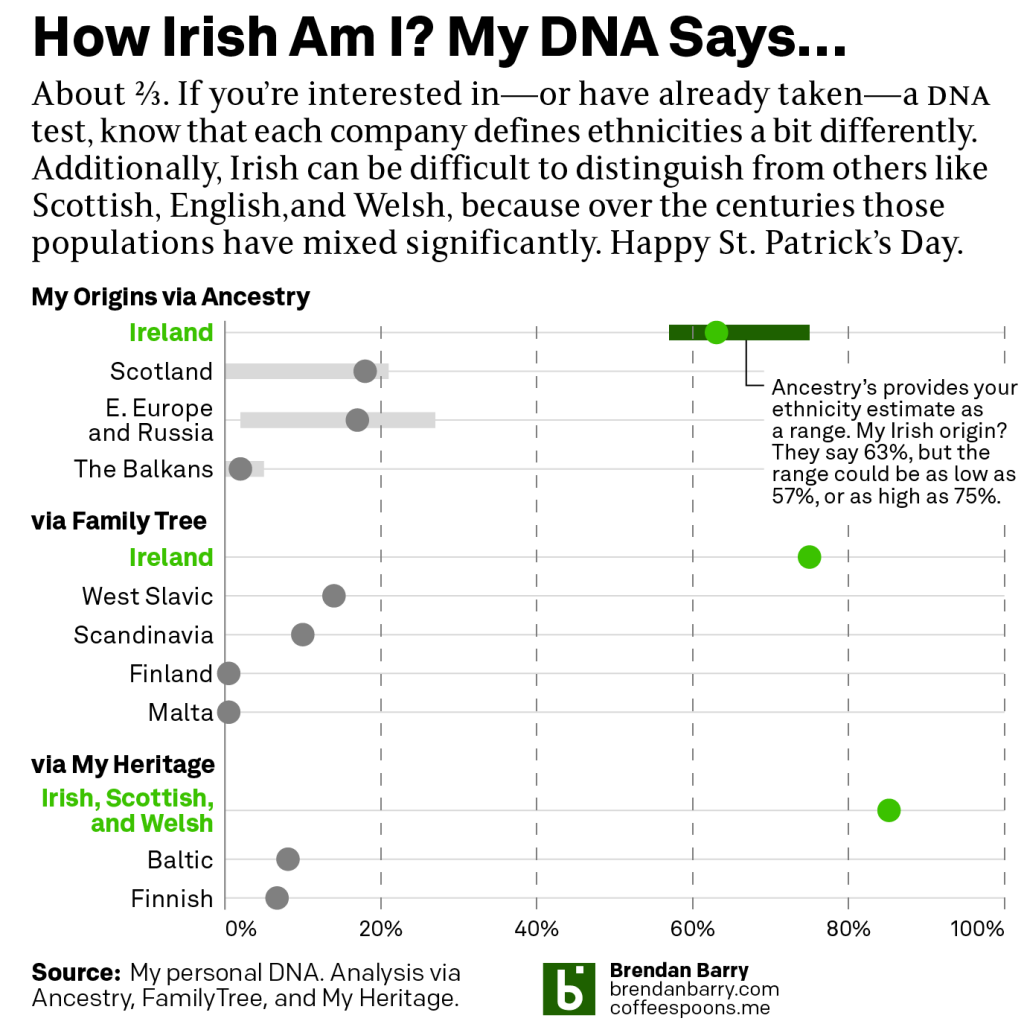

Not surprisingly, I’m pretty Irish.

Of course, if you look at me, those Irish values do not quite equal each other. So what’s the deal? After all, the underlying DNA does not change from spit tube to cheek swab.

The first thing to know is that in one sense, ethnicity is, like so many things, a social construct. Super broadly, every individual is unique—except twins. Of course humans have spread across the globe and in that spread, certain regions have evolved incredibly slight differences between the populations. In addition to those genetic differences, the populations created civilisations and cultures. An ethnicity, in a sense, is a group of people who share that culture, civilisation, and genetic similarities vis-a-vis genetic differences across the world.

Importantly, within those groups, we still have differences. The Irish, for example, are known for freckles and red hair. But not all Irish have those traits. Instead, again super broadly, we say that for a group of people, a certain percentage will share a certain set of features. Consequently, within an ethnic group, you will still have variations and outliers. In some cases because generations ago a traveller from a different group entered the gene pool for some reason or another. And while the offspring might identify entirely with their new civilisation and culture, their genes don’t lie and a DNA test would reveal their traits from their ancestor’s foreign gene pool.

The second point to make is that Ireland is a fairly modern creation. Ireland did not exist as a sovereign state until 1922. Before then, the idea of Ireland existed. The country, however, did not. A better example would be German or Italian. Neither Germany nor Italy existed until the 1870s and 1860s, respectively. If you have “German” ancestors who arrived in Philadelphia in 1848, you don’t have German ancestors. You have ancestors from one of the various principalities or bishoprics comprising the German Confederation. Italy had the Venetian Republic, the Kingdom of the Two Sicilies, and many others. Being Irish, German, or Italian is thus a modern construct.

The third point is that identifying anyone as any of these ethnic groups requires a baseline for a comparison. To do that, you need a reference population in the area you are going to define as Ireland, Germany, or Italy. But humans have migrated throughout history. Ireland was conquered by the English. Germans…well, let’s just say Germans have a history with conquering parts of Europe. And so you can see exchanges of genetic information among populations pretty easily. And over time, those genetic populations evolve.

Take those three points and add them together in admixture test and your results are really only good back to about 500 years. And even then, you may find yourself belonging to something incredibly vague and all-encompassing because, especially as with France and Germany, there’s been too much mixture to get so granular as to fit ourselves within the borders of modern political states.

In the above results, you can see my “Irishness” varies from 63% to 75%. Though, as far as I know 21/32 (66%) of my 3xgreat-grandparents arrived from Ireland. That’s why I say I’m 2/3 Irish. But, genetically, I may be more or less because those 21 might have English or Scottish ancestors. Ancestry says I may be 18% Scottish, but whilst I have ancestors who lived in Scotland, I’m not aware of any ancestors born and raised for multiple generations in Scotland.

And then that’s just how Ancestry defines it. Compare that to my results from My Heritage. Because of the aforementioned difficulty in separating out certain population groups, they lump the Irish, Scottish, and Welsh together. Add my Ancestry Irish and Scottish together and I have 81%, not far from My Heritage’s 85% estimate. Then look at my results from Family Tree. They estimate me as 75% Irish, but add in the 10% Scandinavia and I’m up to 85%.

That brings me to my last point about DNA tests. It’s probably fair to say that I’m something like 80–85% genetically from the British Isles/North Sea region. What about the other 15–20%?

You will often hear you receive half your DNA from each of your parents. And they get half from each of theirs and so on and so forth. I’ve had conversations with folks who take that to mean they get 25% from each grandparent and 12.5% from each great-grandparent et cetera. But that’s not quite true.

You do receive 50% of your DNA from your father and the other 50% from your mother. But that 50%, well that’s a sort of random sample from the share your parents received from their parents.

My maternal grandfather was 100% Carpatho-Rusyn. For generations, his ancestors lived, reproduced, and died in the Carpathian Mountains. If we received exactly half from each previous generation, I should expect 25% of my DNA from my grandfather. But Ancestry, which has the best representation of this small ethnic group, says it’s 17% (though they give it as a range of being between 2 and 27%). In other words, I’m missing seven percentage points.

And so if you take a DNA test and you know you have a great-great grandparents of Irish descent, you may only see a small fraction in your results. If your connection to Ireland (or anywhere else) is even further back, the result becomes smaller still. In fact, beyond 5–7 generations back, you may not even inherit any genetic material from a specific ancestor in your family tree.

But ultimately, for today, as I wrote in one of my very first posts here on Coffeespoons, back in 2010, on St. Patrick’s Day, we’re all at least a little bit Irish.

Hopefully next year we’ll be able to celebrate in person.

Credit for the piece is mine.