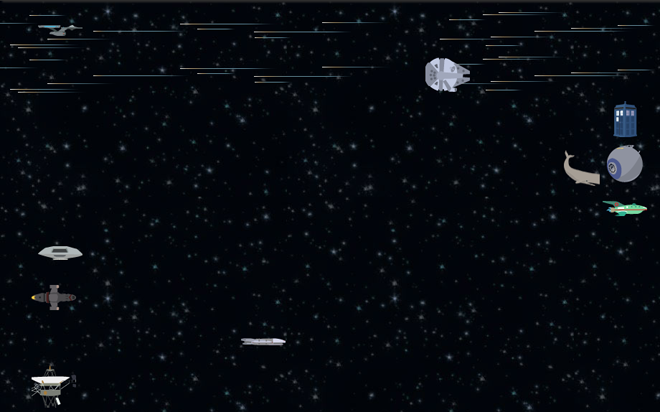

First of all, I grew up a fan of Star Trek and not Star Wars. Star Trek is, after all, more science-y. Now, for today’s post, I could make references to the battlestar Galactica, the good ship Tardis, Planet Express deliveries, or avoiding the Alliance throughout the Verse. Instead I’ll just submit this interactive graphic from Slate.

It compares the times needed by various nerd-loved starships/spaceships/space vehicles to reach very distant (and real) stellar destinations. Don’t worry, there is a bar chart in the end with Voyager 1 thrown in for comparison to reality. (Though I suppose they could have just made it Voyager 6.)

See, a bar chart. It fits within the scope of this blog.

Credit for the piece goes to Chris Kirk, Andrew Morgan, and Natalie Matthews.