I spent way more time trying to craft that title than I’d like to admit. Headline writing is not easy.

Quick little piece today about Sankey diagrams. I love them. You often see them described as flow diagrams—this piece is in the article we’ll get to shortly—but they are more of a subset within a flow diagram. What sets Sankeys apart is their use of proportional strokes or widths of the directional arrows to indicate share of movement.

The graphic in question comes from an article about Major League Baseball’s (MLB’s) problem with “sticky stuff”. For the unfamiliar, sticky stuff is a broad term for foreign substances pitchers put on their fingers to provide better grip on the baseball. A better grip makes it easier to create movement like sliding and sinking in a pitch there therefore makes it harder for a hitter to hit it. Back when I was a wannabe pitcher, it was spitballs and scuff balls. Now professionals use things like Spider Tack. These are substances that allow you to put the ball in the palm of your hand, then turn your hand over to face the ground and not have the ball fall out of your hand.

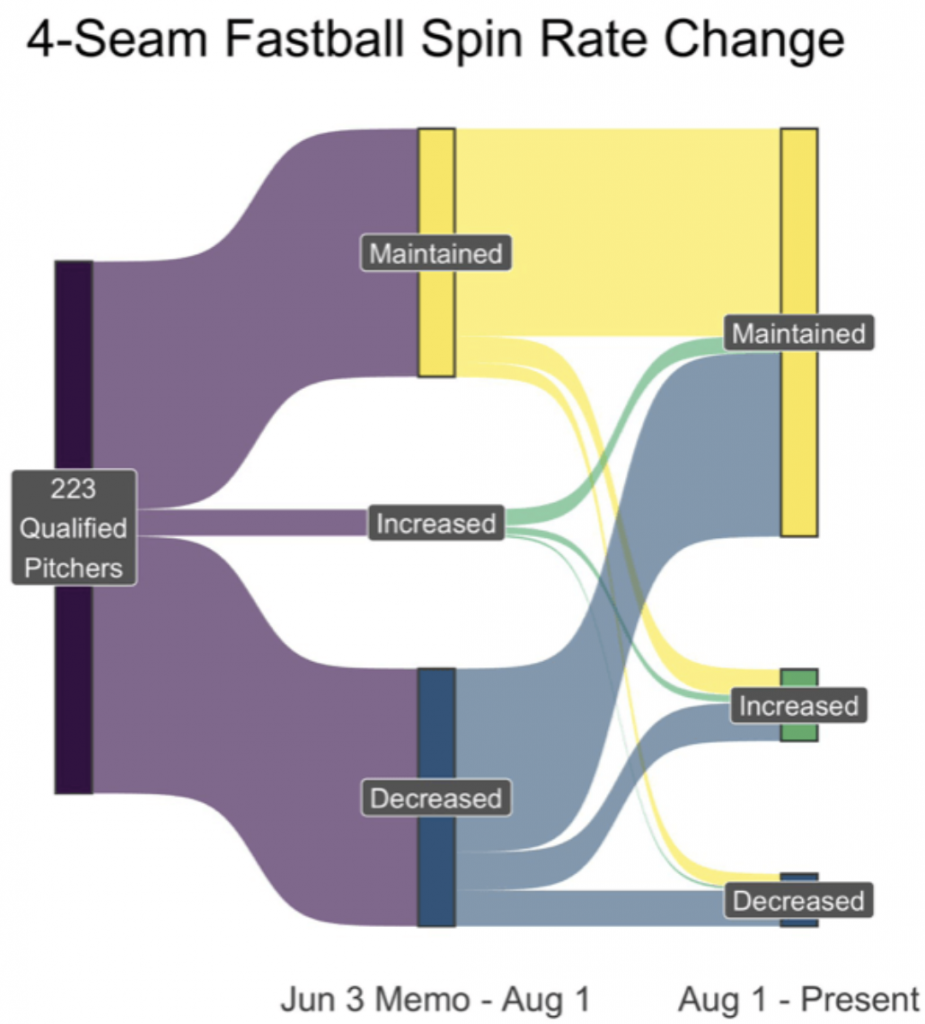

So the graphic looks at starting pitchers and how their spin rate, the quantifiable measure impacted by sticky stuff, of their fastballs has changed since MLB instituted a ban on sticky stuff. (It had actually long been in place, see spitballs for example, but had rarely been enforced.)

This graphic explores how 223 pitchers saw their spin rates change in the first two months after the change in policy was announced to the nearly month after that period.

Sankeys use proportional width not just to show movement from category to category but the important element of what share of which category moves to which category. For example, we can see a little less than half of starting pitchers saw their spin rates stay the same after the policy change and another almost equal group saw their spin rates decrease. That’s probably a sign they were using sticky stuff and stopped lest they get caught.

But we can then see of that group, maybe 1/6 then saw their spin rates increase again over the last month. That could be a sign that they have found a way to evade the ban. Though it could also be they’ve found new ways of gripping or throwing the baseball. Spin rate alone does not prove sticky stuff usage.

Similarly, we can see that in the group that maintained their spin rate, a small group has found a way to increase it. Finally, a small fraction of the original 223 saw their spin rates increase and a fraction of that group has seen their spin rates increase even further.

This was just a really nice graphic to see in an article from the Athletic about sticky stuff and its potential return.

Credit for the piece goes to Max Bay.