Tag: data visualisation

-

Mission Accomplished

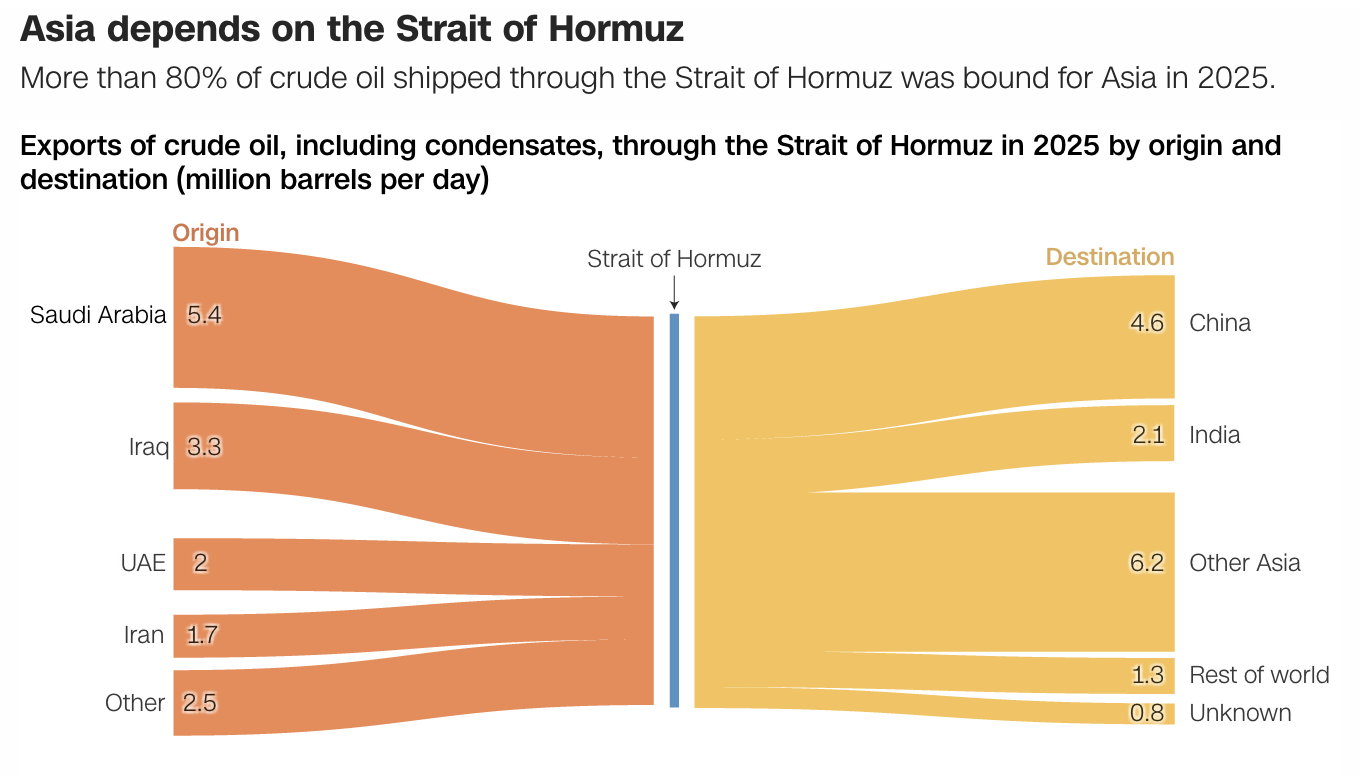

Last weekend the United States and Israel preemptively struck Iran and kicked off a regional war. As I type this Monday morning, the US–Israeli strike forced assassinated the ayatollah and numerous other senior Iranian officials—but this seems to have been anticipated to a degree and the regime quickly retaliated and has delegated roles and responsibilities.…

-

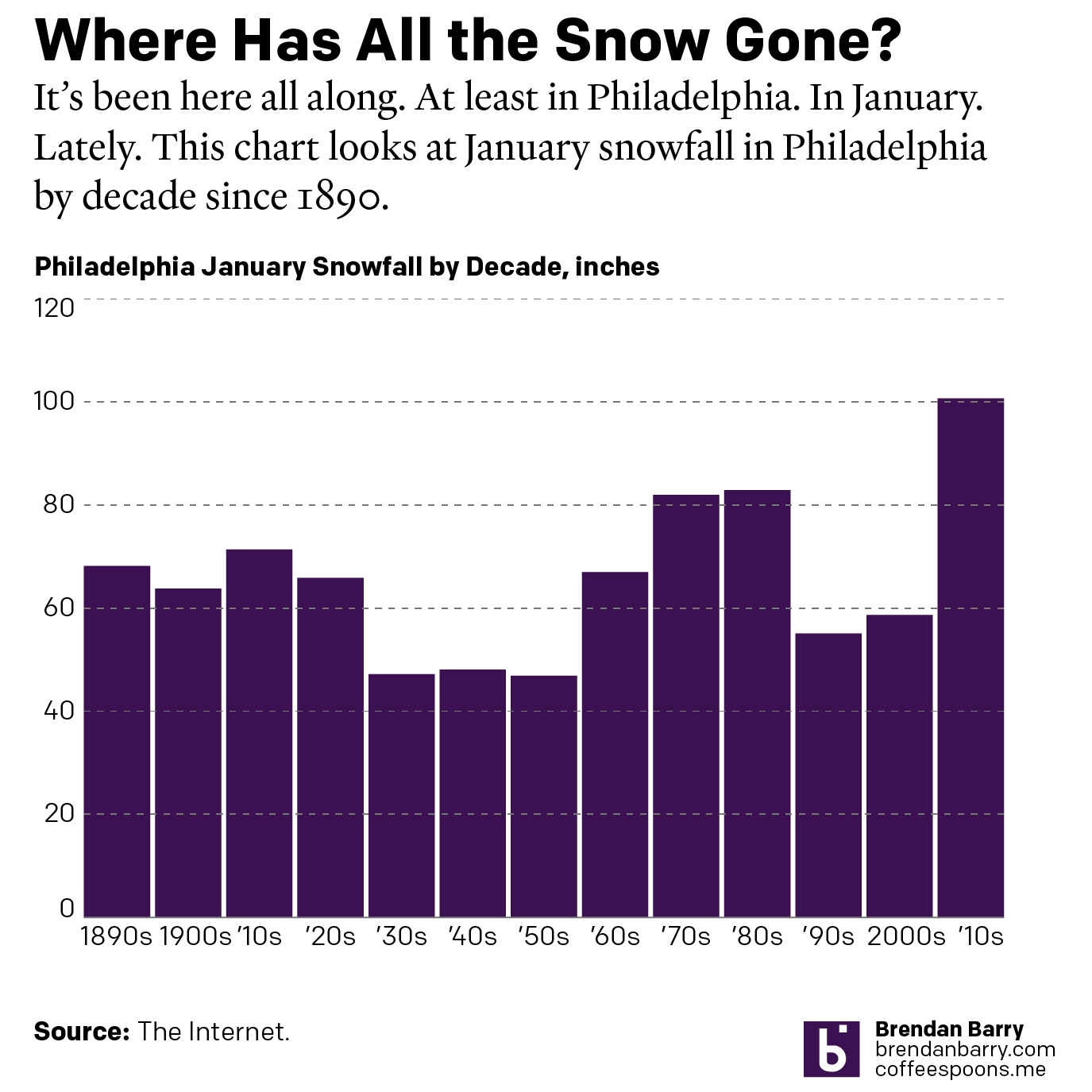

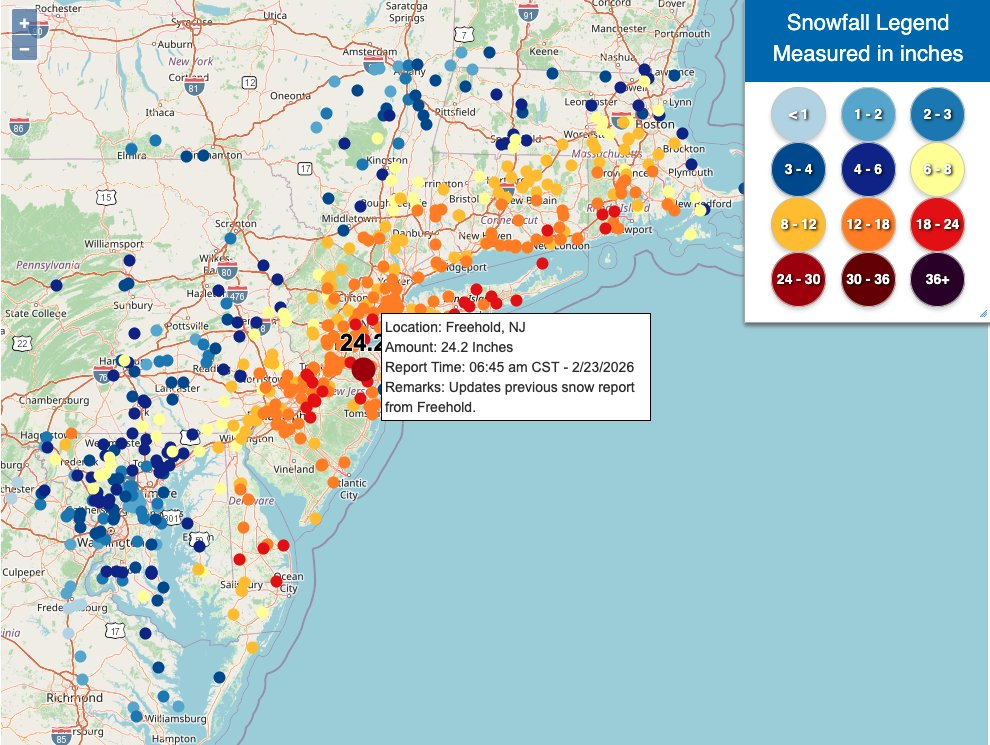

Winter Is Still Here

Ah, a blizzard. Even if the worst of the storm that recently impacted Philadelphia struck mostly at night, it still left a picturesque mess for the morning. I, however, was struck by some of the maps of the snowfall totals and I figured that would be worth sharing today. What got me started on this…

-

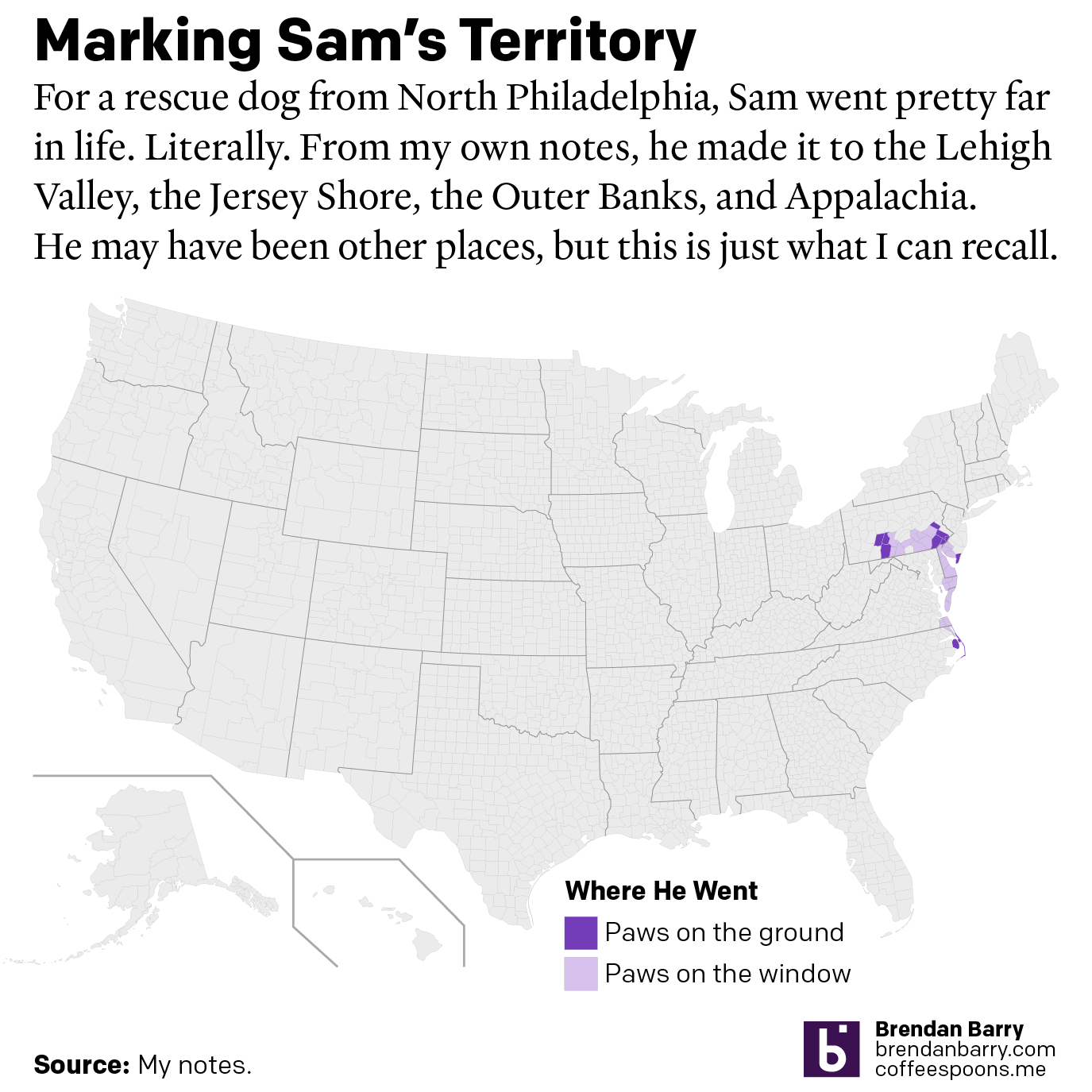

A Ruff Week

After last Friday’s post went live I headed home, because I received word that in the evening, we would be saying farewell to our family dog of 17 years, Sam. My sister adopted him after his first owners gave him up to a rescue shelter with injuries they could not afford to tend after he…

-

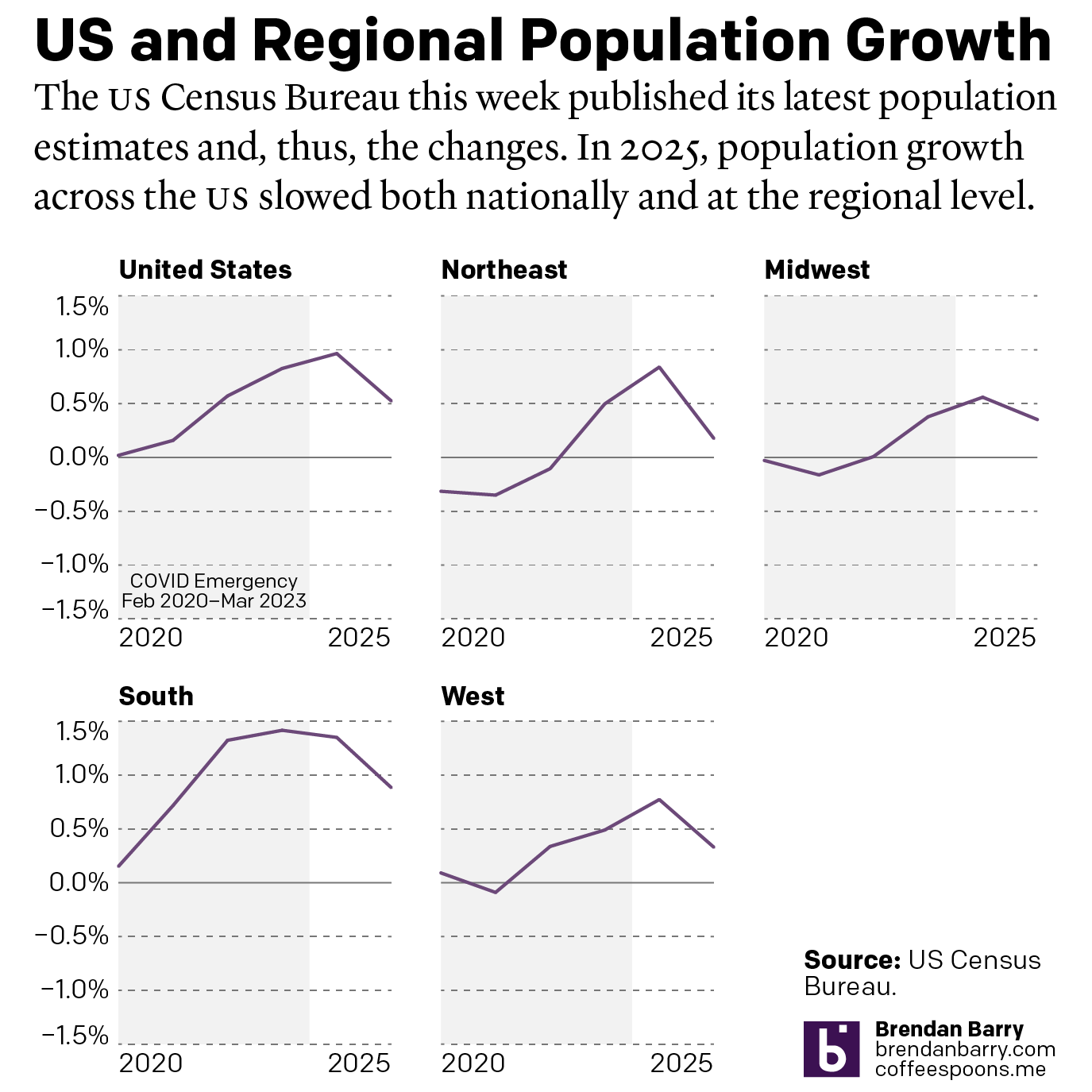

The Slowing of the Growth

This week the US Census Bureau released their population estimates for the most recent year and that includes the rate changes for the US, the Census Bureau defined regions, and the 50 states and Puerto Rico. I spent this morning digging into some of the data and whilst I will try to later to get…

-

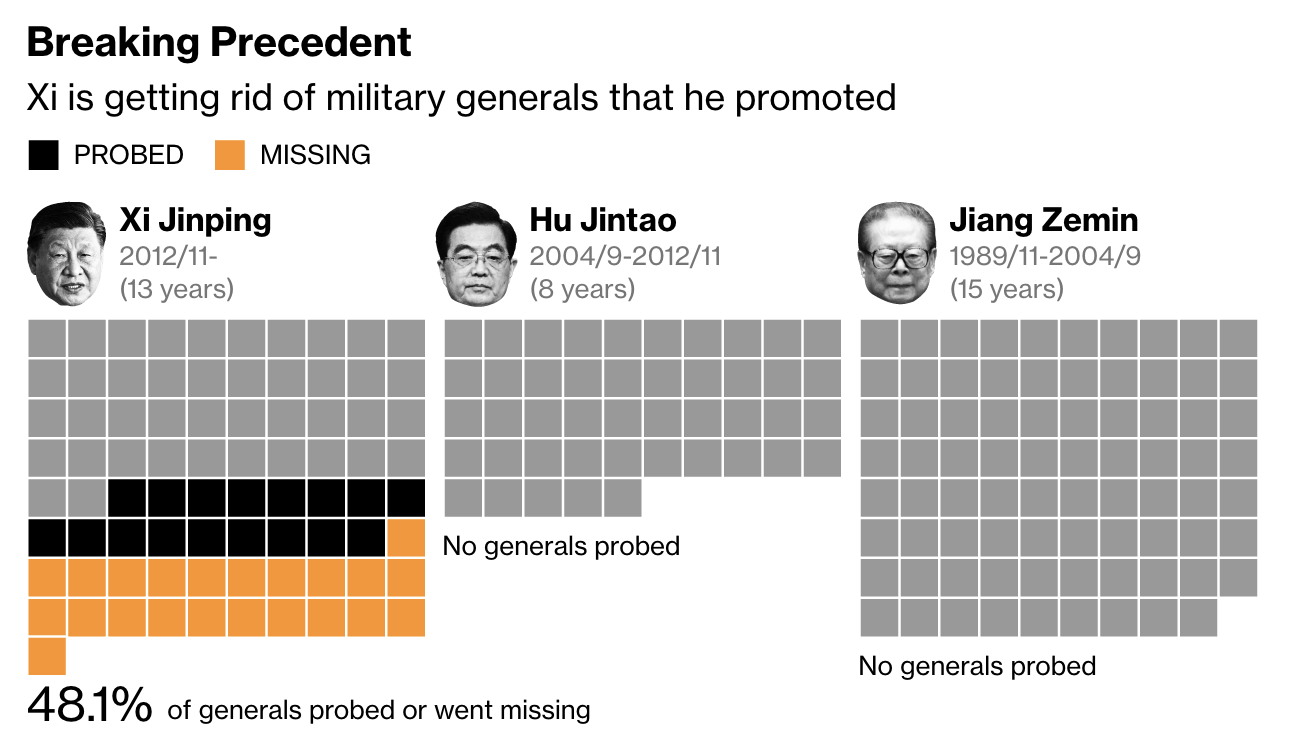

Xi-nnie the Pooh Purges the PLA

This past weekend, Xi Jinping, the leader of China, purged the top leadership of the People’s Liberation Army (PLA), the armed forces of the People’s Republic of China. Purges themselves are nothing new as Xi has solidified his iron grip on the country and its political leadership in the Chinese Communist Party. But unlike his…

-

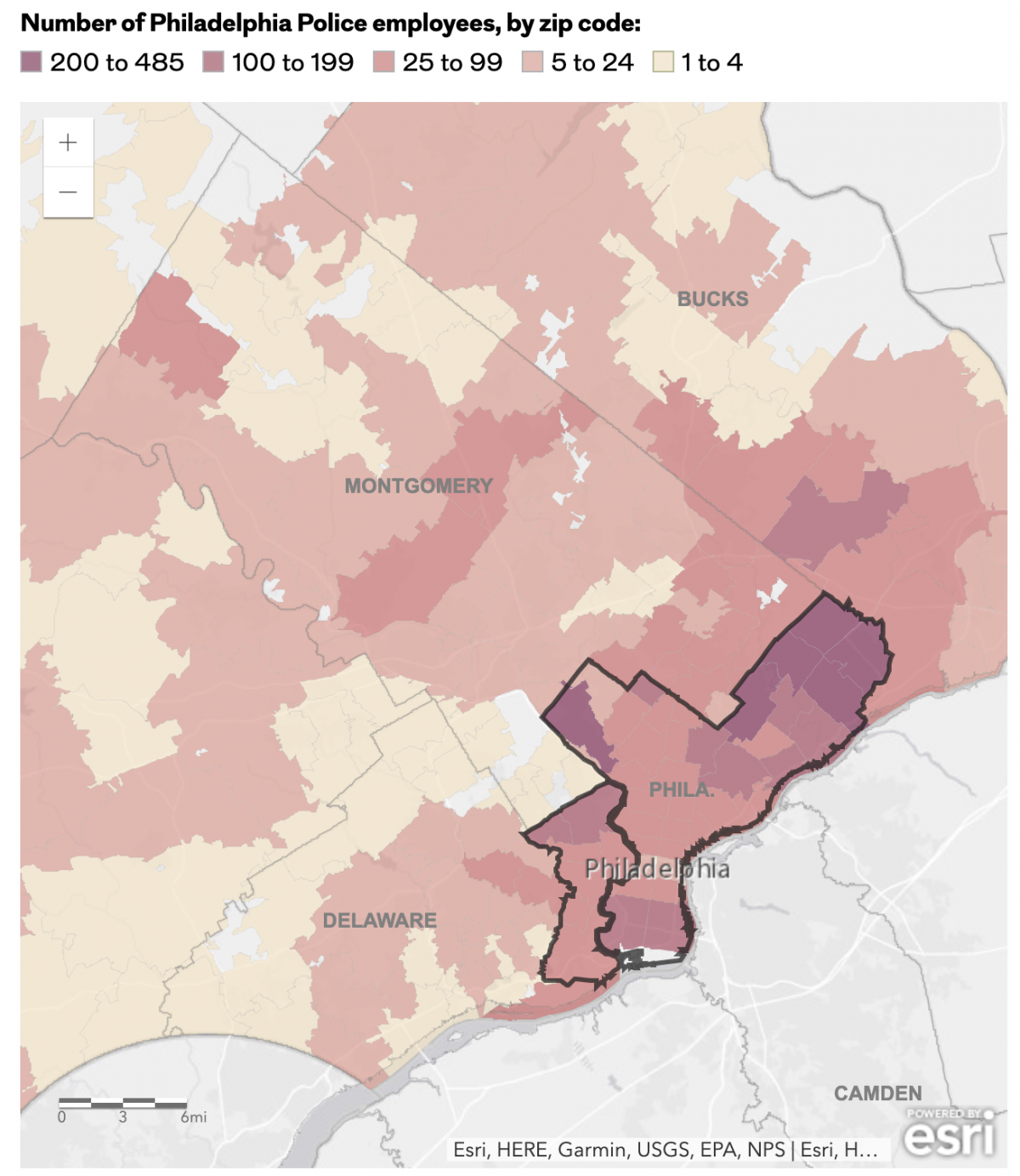

The Philadelphia Beat is Pretty Big

Early last week I read an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer about where the city’s police officers live, an important issue given the city’s loose requirement they reside within the city limits. Whilst most do, especially in the far Northeast, the Northwest, and South Philadelphia, a significant number live outside the city. (The city of…

-

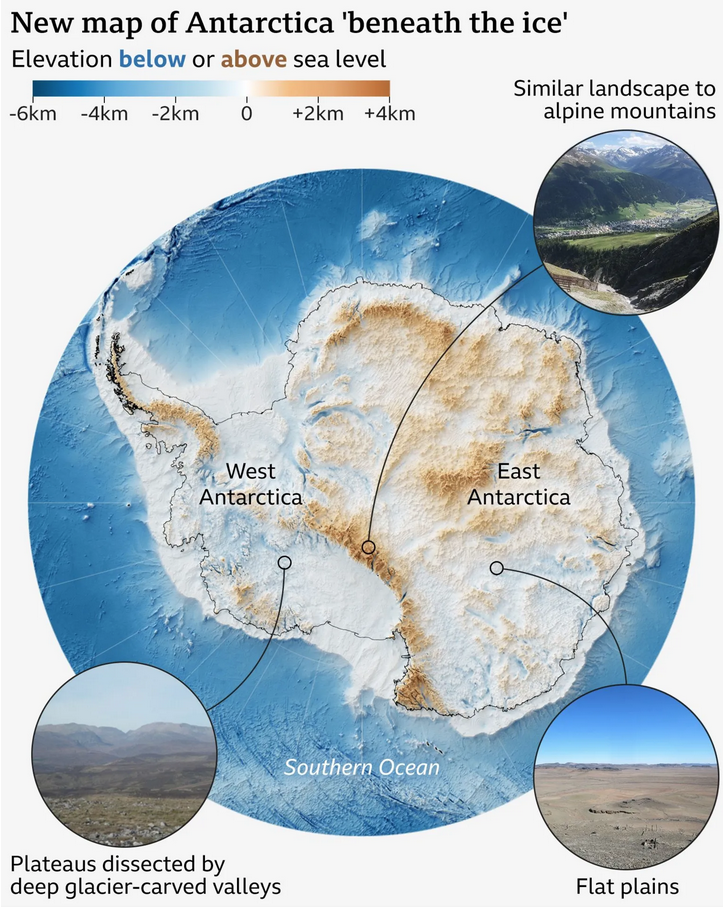

A View Beneath the Ice

I love maps. And above the ocean’s surface, we generally have accurate maps for Earth’s surface with only two notable exceptions. One is Greenland and its melting ice sheet is, in part, contributes to the emerging conflict between the United States and Denmark over the island’s future. The other? Antarctica. Parts of the East Antarctic…