Tag: dot plot

-

Revisiting My 2025 Red Sox Predictions

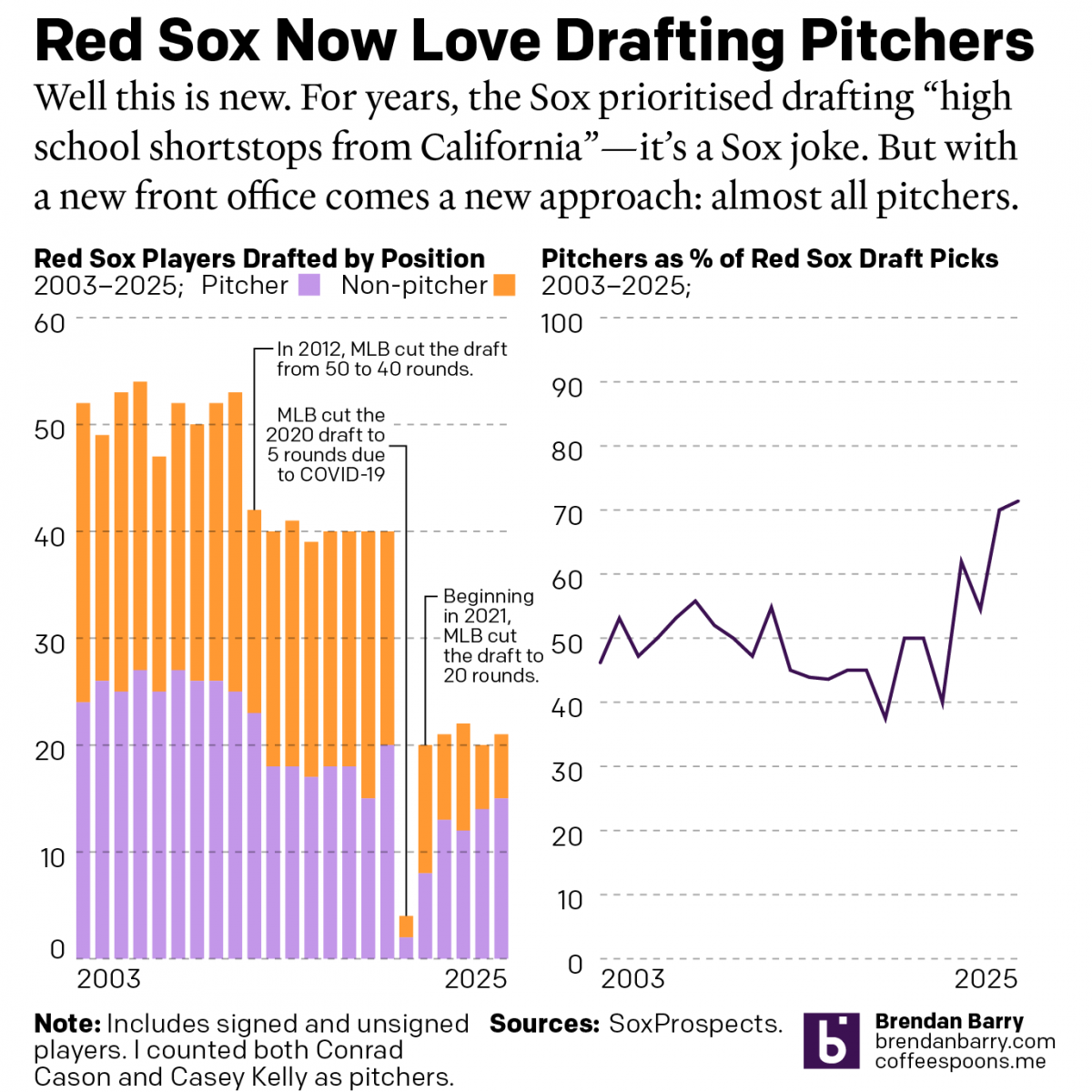

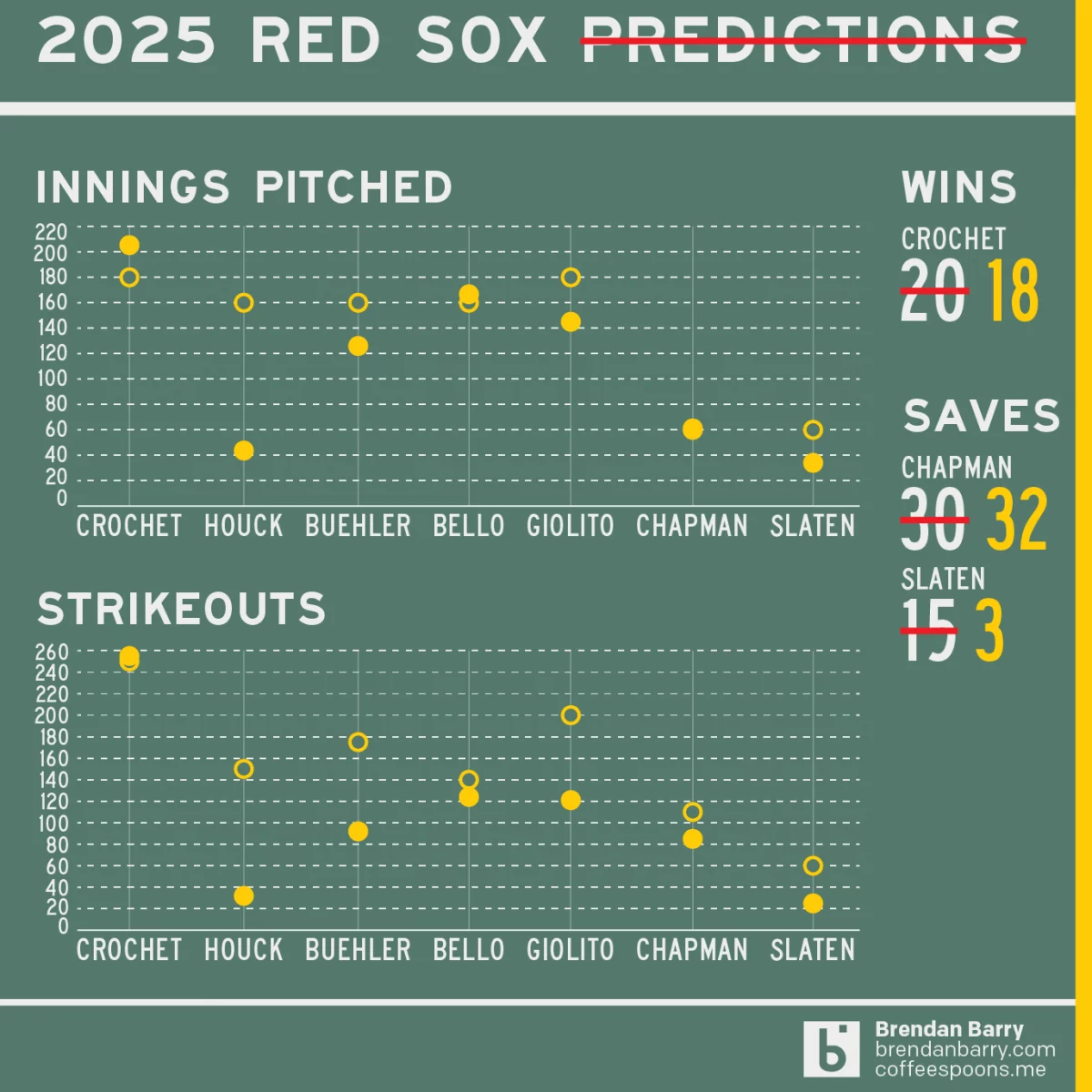

Back in March I posted my predictions for the 2025 Boston Red Sox on my social media feeds. I chose not to post it here, because the images had no real data visualisation and the only real information graphic was my prediction of the playoffs via a bracket. I did, however, write about how the…

-

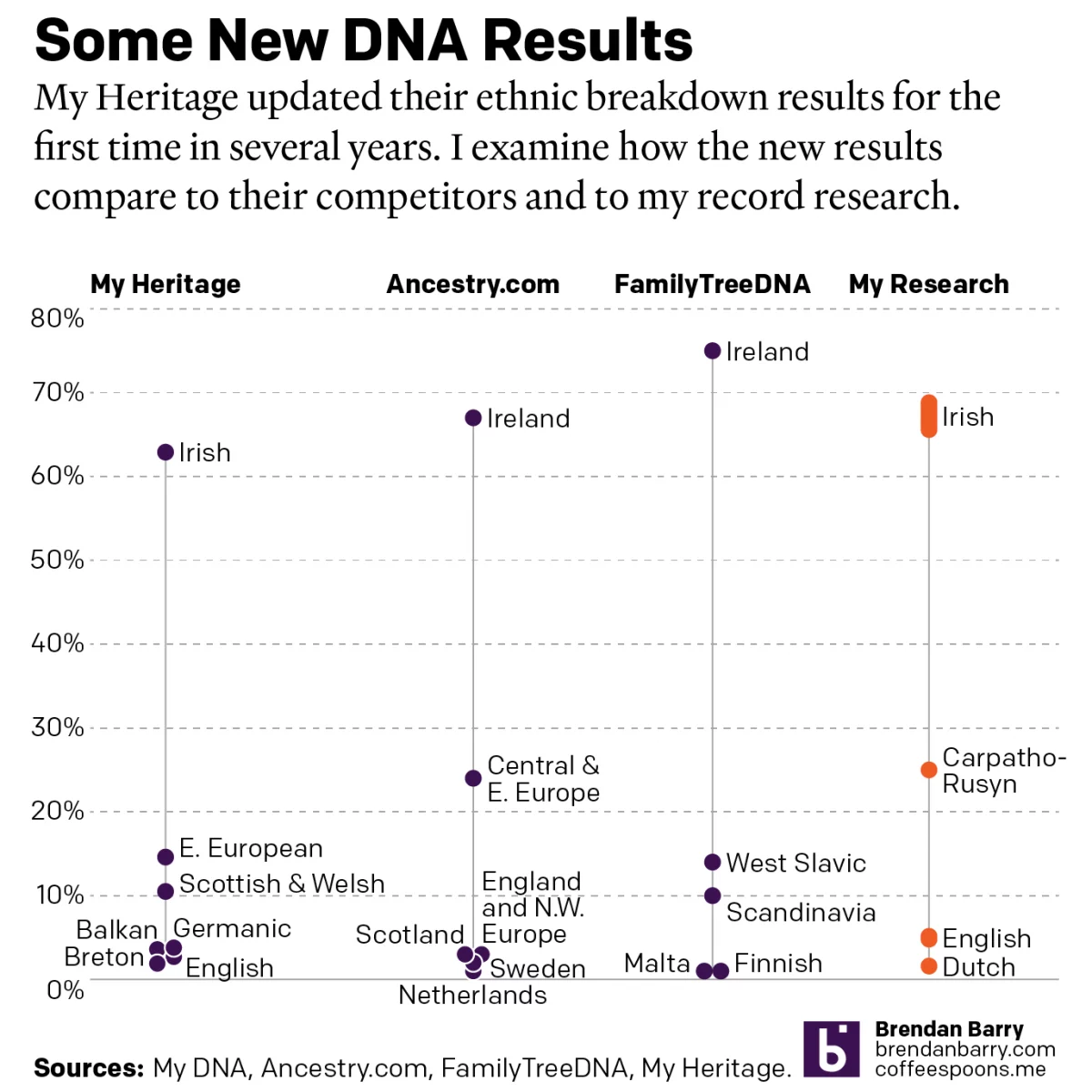

A Refreshed Look at My Ethnic Heritage

Late last week I received an update on my ethnic breakdown from My Heritage, a competitor of Ancestry.com and other genealogy/family history/genetic ancestry companies. For many years, the genealogical community had been waiting for this long-promised update. And it has finally arrived. For my money, My Heritage’s older analysis, v0.95, did not align with my…

-

The Great British Baking

Recently the United Kingdom baked in a significant heatwave. With climate change being a real thing, an extreme heat event in the summer is not terribly surprising. Also not surprisingly, the BBC posted an article about the impact of climate change. The article itself was not about the heatwave, but rather the increasing rate of…

-

Graduate Degrees

Many of us know the debt that comes along with undergraduate degrees. Some of you may still be paying yours down. But what about graduate degrees? A recent article from the Wall Street Journal examined the discrepancies between debt incurred in 2015–16 and the income earned two years later. The designers used dot plots for…

-

Those Are Some Heavy Balls

Unfortunately, I don’t subscribe to Business Insider, but I saw this graphic on the Twitter and felt the need to share it. Primarily because baseball will almost certainly stop at midnight when the owners of the teams will impose a lockout (as opposed to players going on strike). And with that baseball will be on…

-

Low Expectations

Today the 2021 Major League Baseball season begins its playoffs. Tomorrow we get the Los Angeles Dodgers and the St. Louis Cardinals. Why the Dodgers, the team with the second-best record in all of baseball, need to play a one-game play-in is dumb, but a subject for perhaps another post. Tonight, however, is the American…

-

Updated DNA Ethnicity Estimates

Earlier this year I posted a short piece that compared my DNA ethnicity estimates provided by a few different companies to each other. Ethnicity estimates are great cocktail party conversations, but not terribly useful to people doing serious genealogy research. They are highly dependent upon the available data from reference populations. To put it another…