Category: Datagraphic

-

Let There Be Light

In several decades… Just a quick little piece today, a neat illustration from the BBC that shows how the process of nuclear fusion works. The graphic supports an article detailing a significant breakthrough in the development of nuclear fusion. Long story short, a smaller sort-of prototype successfully proved the design underpinning a much larger fusion…

-

Dots Beat Bars

Today is just a quick little follow-up to my post from Monday. There I talked about how a Boston Globe piece using three-dimensional columns to show snowfall amounts in last weekend’s blizzard failed to clearly communicate the data. Then I showed a map from the National Weather Service (NWS) that showed the snowfall ranges over…

-

How Accurate Is Punxsutawney Phil?

For those unfamiliar with Groundhog Day—the event, not the film, because as it happens your author has never seen the film—since 1887 in the town of Punxsutawney, Pennsylvania (60 miles east-northeast of Pittsburgh) a groundhog named Phil has risen from his slumber, climbed out of his burrow, and went to see if he could see…

-

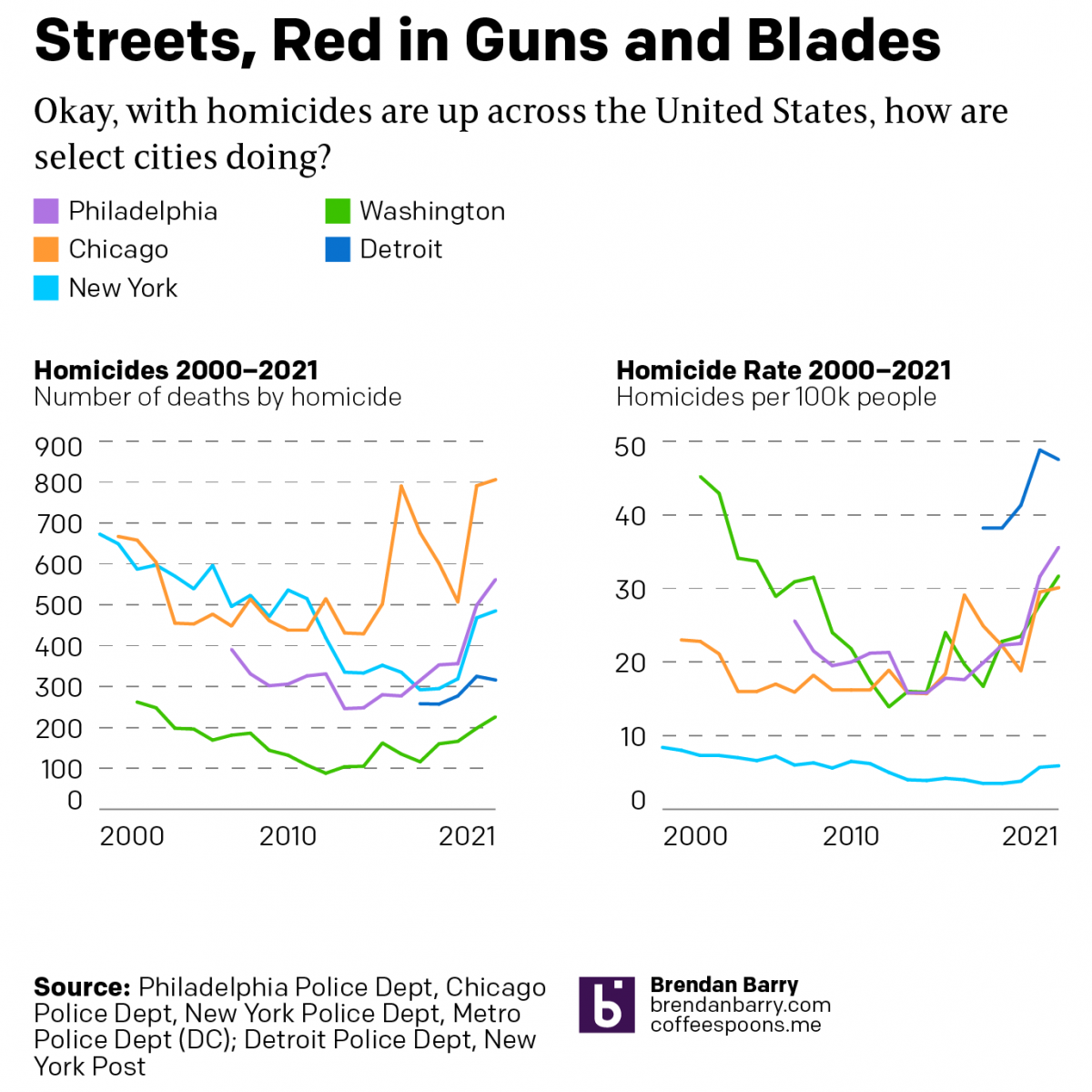

America’s Crime Problem

During the pandemic, media reports of the rise of crime have inundated American households. Violent crimes, we are told, are at record highs. One wonders if society is on the verge of collapse. But last night a few friends asked me to take a look at the data during the pandemic (2020–2021) and see what…

-

Obfuscating Bars

On Friday, I mentioned in brief that the East Coast was preparing for a storm. One of the cities the storm impacted was Boston and naturally the Boston Globe covered the story. One aspect the paper covered? The snowfall amounts. They did so like this: This graphic fails to communicate the breadth and literal depth…

-

I Call Them Life Tiles

Happy Friday, everyone. Here in the United States’ Northeast Corridor we’re looking forward to a potentially powerful nor’easter that could be the first real snowstorm to hit Philadelphia all winter. (Dumb La Niña.) But I’ve also recently started working in a new sketchbook. (It happens often.) But that’s why I thought this graphic from Indexed…

-

How the Globe’s Writers Voted

Yesterday we looked at a piece by the Boston Globe that mapped out all of David Ortiz’s home runs. We did that because he has just been voted into baseball’s Hall of Fame. But to be voted in means there must be votes and a few weeks after the deadline, the Globe posted an article…

-

558 Dingers

Yesterday baseball writers elected David Ortiz of the Boston Red Sox, better known as Big Papi, to the Baseball Hall of Fame. I was trying to work on a thing for yesterday, but ran out of time. While I will attempt to return to that later, for now I want to share a simple interactive…