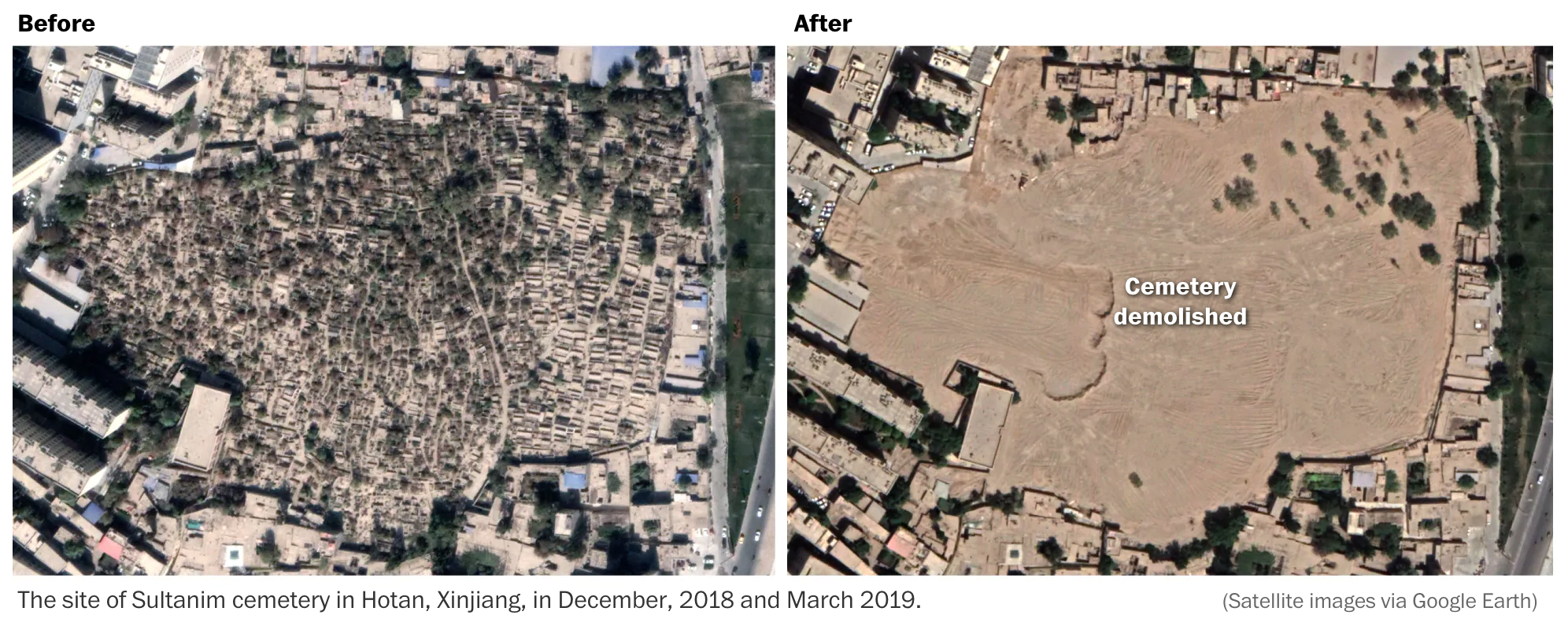

For those who don’t know, China currently engages in ethnocide, or cultural genocide in its western province of Xinjiang, a province with a majority of its population being Uighurs, a Turkic Muslim people. Ethnocide is a term I prefer over genocide as genocide more commonly refers to practices like those in Nazi Germany or 1990s Rwanda and Bosnia wherein people are systematically executed and murdered. Ethnocide leaves a people alive but aims to destroy and extinguish their culture ultimately replacing it with that of another. In this case, Beijing’s policy is to strip the Uighurs of their Muslim culture and identity and replace it with loyalty to China and the Chinese Communist Party.

The BBC have just published what they call the Xinjiang Police Files, files and data hacked off of Chinese government servers and then handed over to a US-based expert on Xinjiang and the atrocities there. That person then handed copies to the BBC, which has verified much of the content.

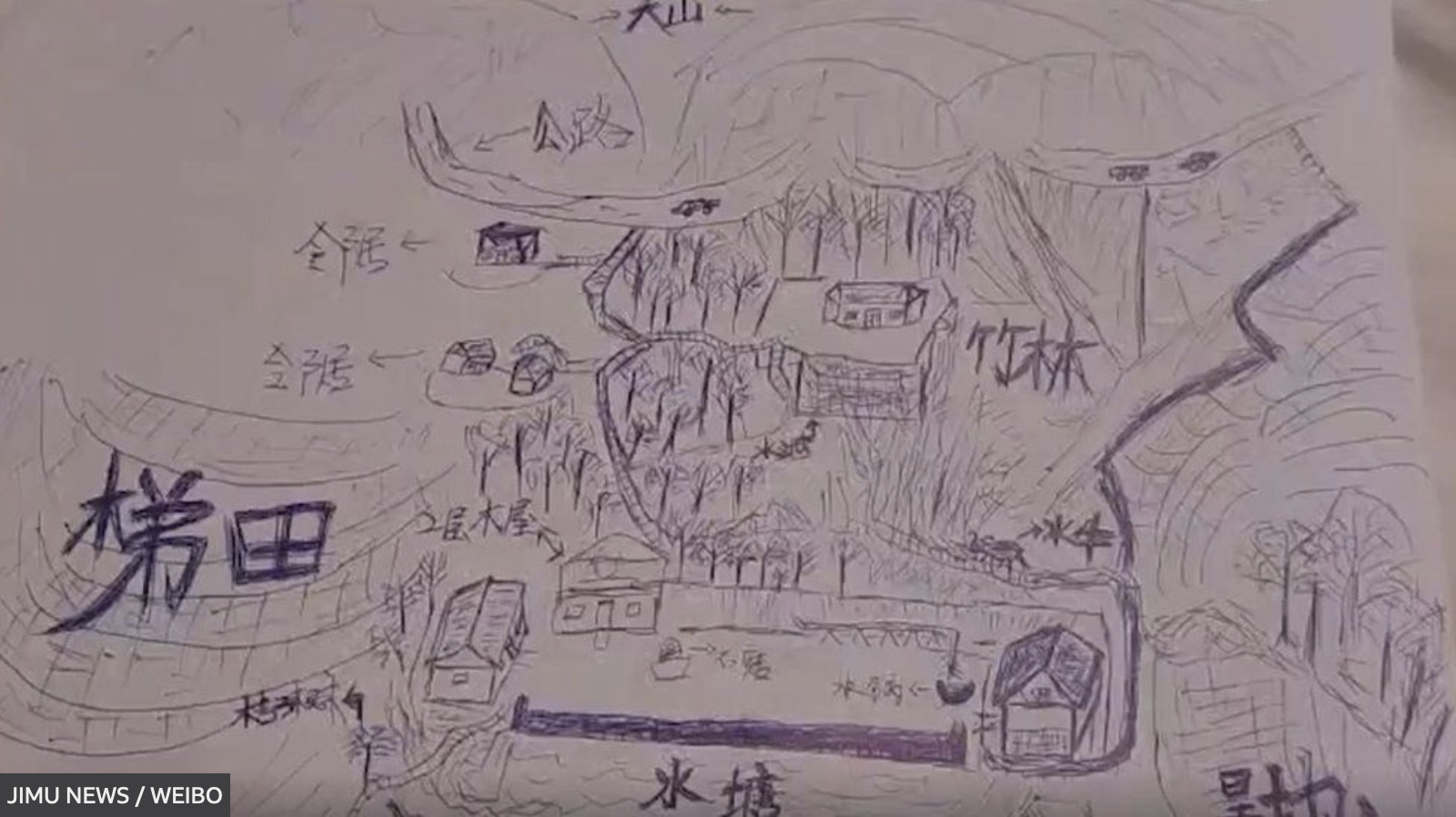

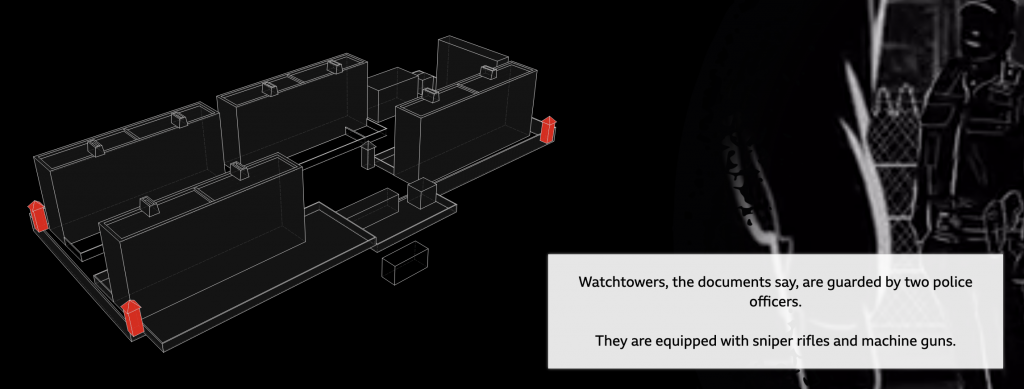

There is not much by way of data visualisation or information design, but the story is worth mentioning because maybe over one million people are being forcibly detained and “re-educated” by Beijing. One of the articles about the files, however, does have a small graphic of one of the “re-education camps”, i.e. prison, and details its design and the facilities therein.

Political liberalism and pluralism are messy. Often it means we hear and listen to things with which we disagree, sometimes vehemently. Freedom of speech, expression, and religion can make us feel uncomfortable, hurt our feelings, and even sick to our stomachs. But that is also the price of our liberty to speak, express, and pray ourselves. Because we only need to look to China to see what happens when a society or a government decides what is or isn’t acceptable speech (peaceful protests against the government), expression (growing out a beard), or religion (praying in a mosque). An authoritarian regime, an anti-liberal regime, will attempt to stifle, silence, and ultimately imprison those who go against the (Chinese Communist) party line.

1984 rings a little more true each year.

Credit for the piece goes to John Sudworth and the BBC’s Visual Journalism Team.