Tag: data visualisation

-

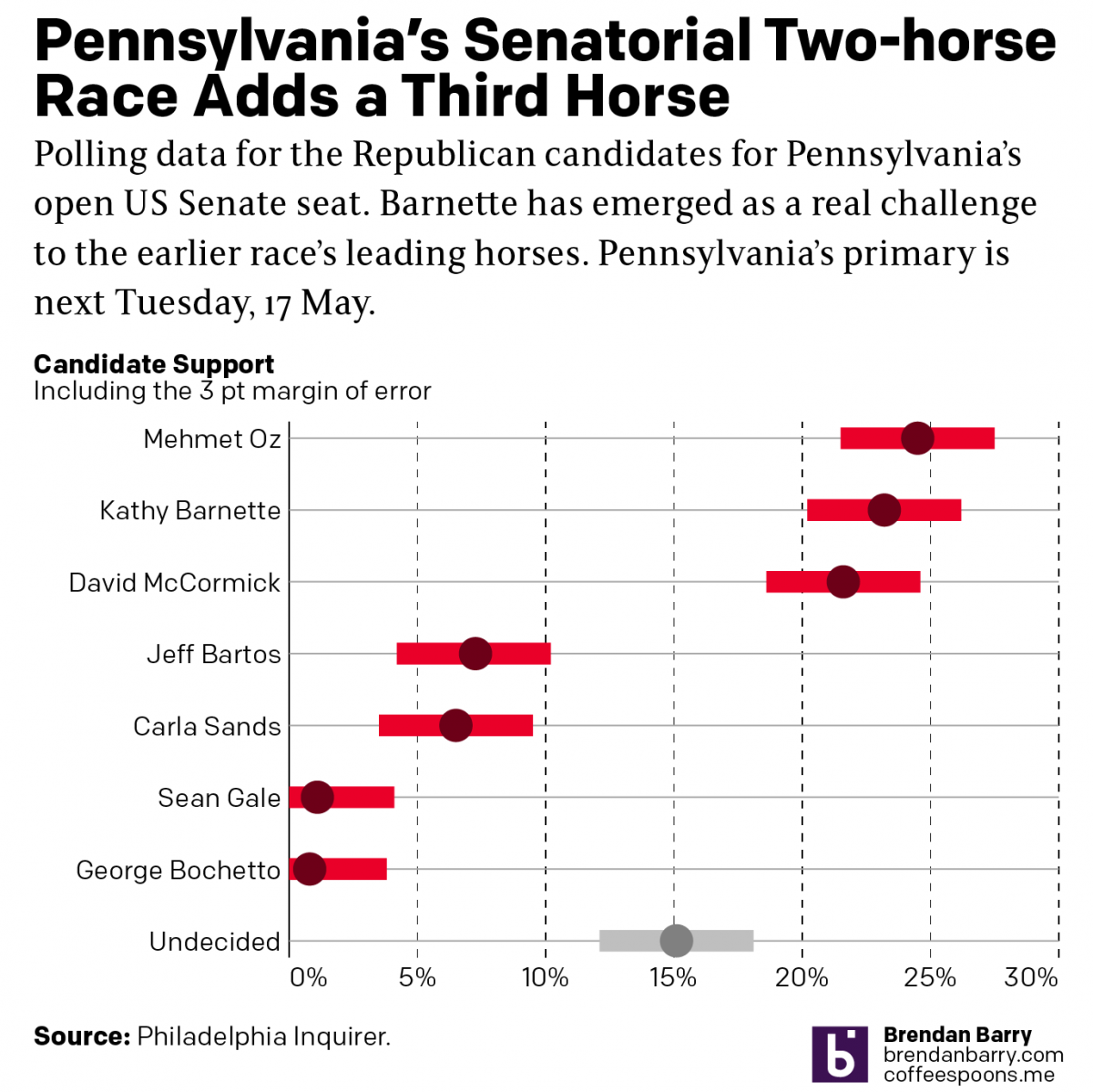

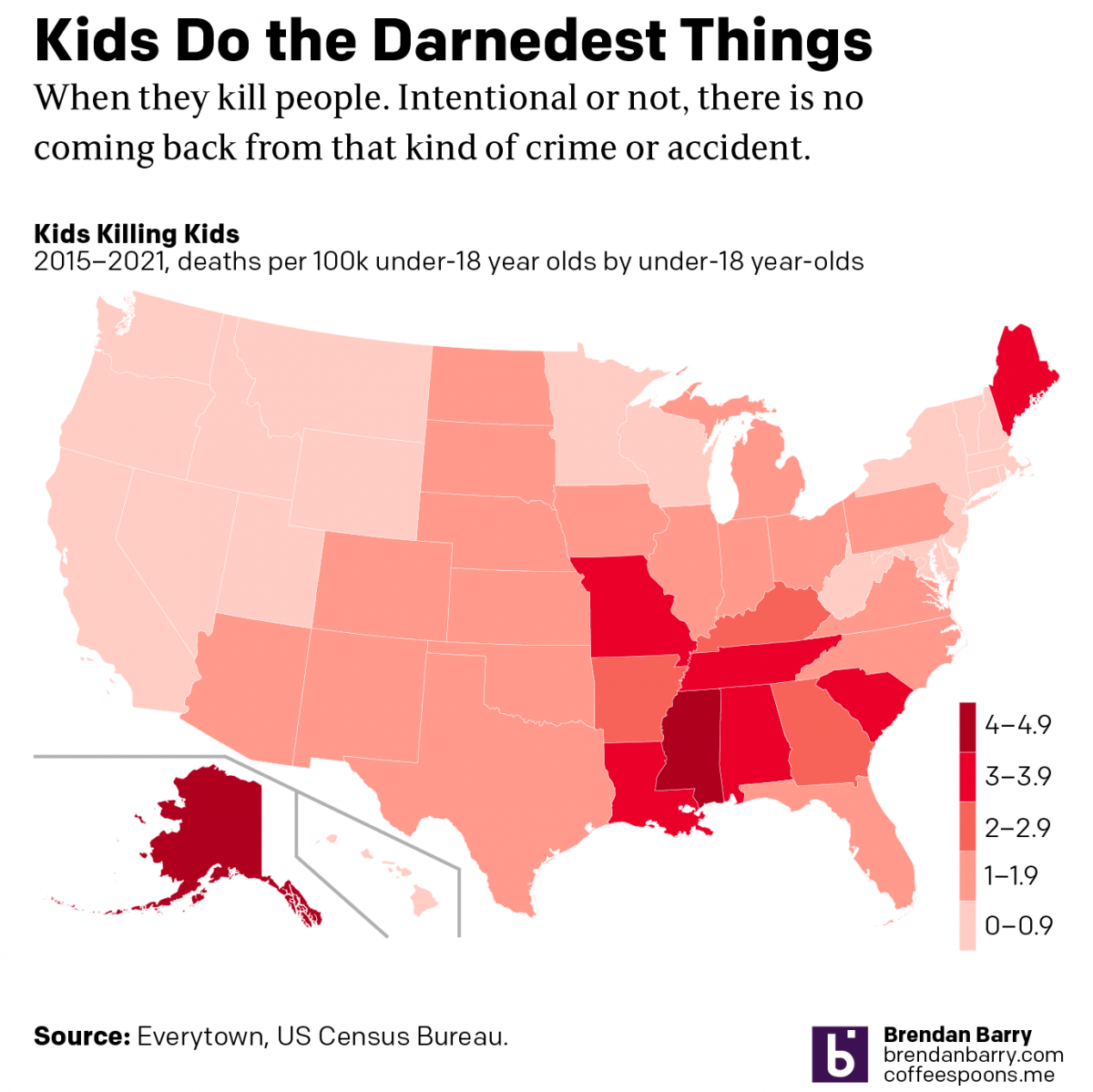

Kids Do the Darnedest Things: Shoot Other Kids

Last month, a 2-year old shot and killed his 4-year old sister whilst they sat in a car at a petrol station in Chester, Pennsylvania, a city just south of Philadelphia. Not surprisingly some people began to look at the data around kid-involved shootings. One such person was Christopher Ingraham who explored the data and…

-

One Million Covid-19 Deaths

This past weekend the United States surpassed one million deaths due to Covid-19. To put that in other terms, imagine the entire city of San Jose, California simply dead. Or just a little bit more than the entire city of Austin, Texas. Estimates place the number of those infected at about 80 million. Back of…

-

The B-52s

Not the band, but the long-range strategic bomber employed by the United States Air Force. This isn’t strictly related to Ukraine, but it’s military adjacent if you will. I thought about creating a graphic a few years ago to celebrate the longevity of the B-52 Stratofortress, more commonly called the BUFF, Big Ugly Fat Fucker.…

-

Battalion Tactical Groups

As Russia redeploys its forces in and around Ukraine, you can expect to hear more about how they are attempting to reconstitute their battalion tactical groups. But what exactly is a battalion tactical group? Recently in Russia, the army has been reorganised increasingly away from regiments and divisions and towards smaller, more integrated units that…

-

Where’s My (State) Stimulus?

Here’s an interesting post from FiveThirtyEight. The article explores where different states have spent their pandemic relief funding from the federal government. The nearly $2 trillion dollar relief included a $350 billion block grant given to the states, to do with as they saw fit. After all, every state has different needs and priorities. Huzzah…

-

There Goes the Shore

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) released its 2022 report, Sea Level Rise Technical Report, that details projected changes to sea level over the next 30 years. Spoiler alert: it’s not good news for the coasts. In essence the sea level rise we’ve seen over the past 100 years, about a foot on average,…