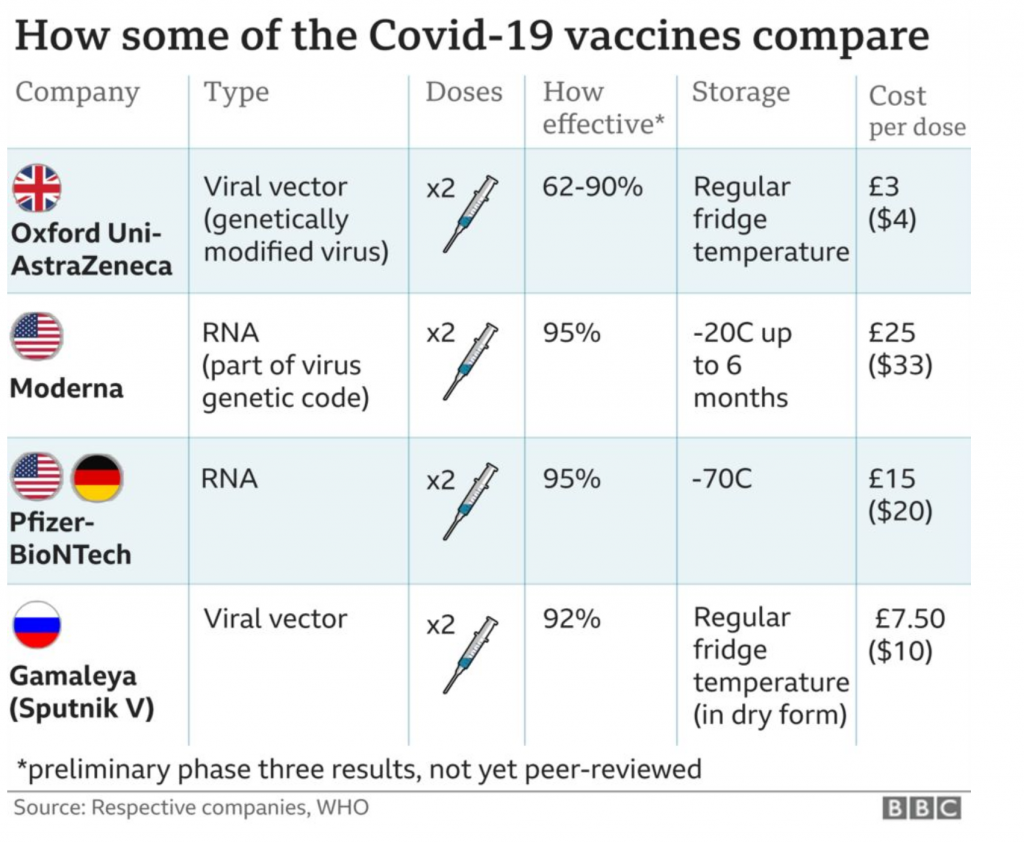

With the rollout of the first vaccination programme in the United Kingdom, the BBC had a helpful comparison table stating the differences between the four primary options. It’s a small piece, but as I often say, we don’t necessarily need large and complex graphics.

Since there are only four vaccines to compare and only a handful of metrics, a table makes a lot of sense.

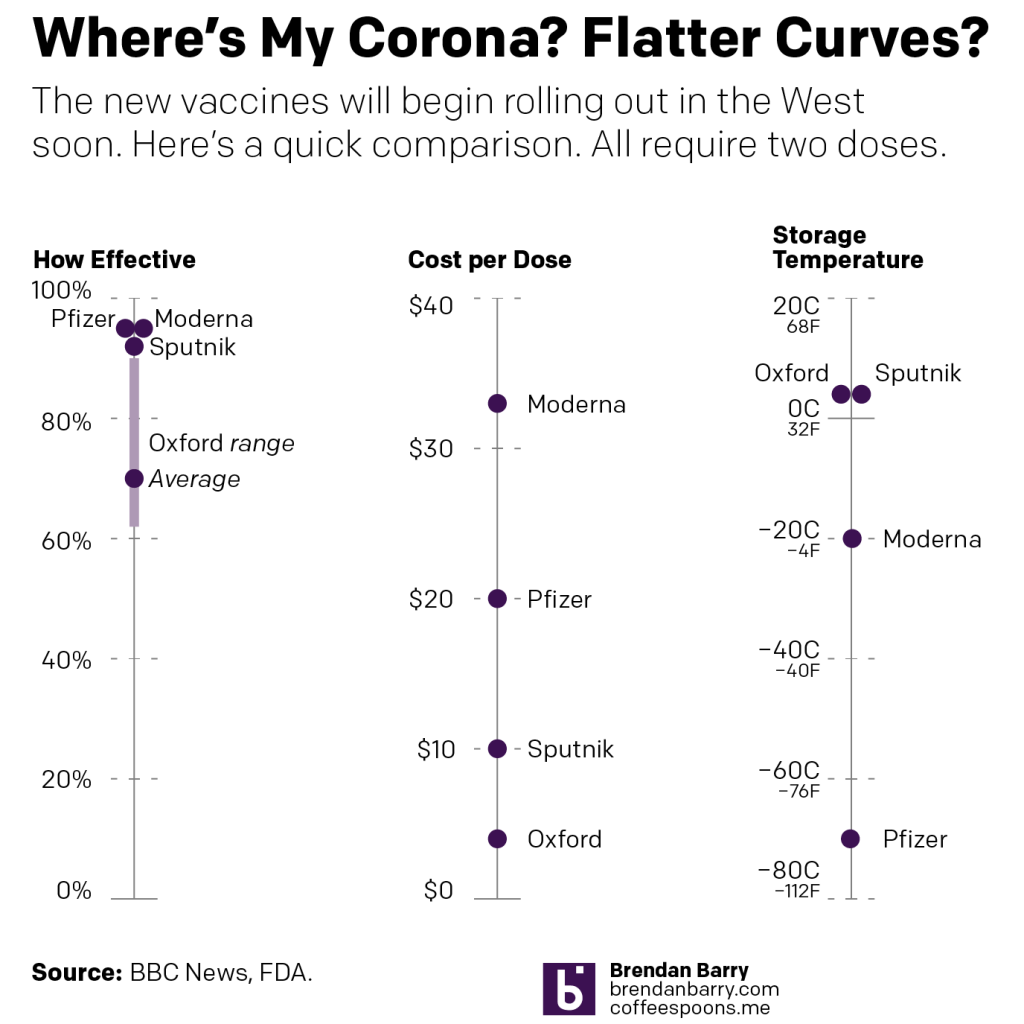

But I wanted to take it a step further and so I threw together a quick piece that showed some of the key differences. In particular I wanted to focus on the effectiveness, storage temperatures (key to distribution in the developing world), and cost.

You can pretty quickly see why the United Kingdom’s vaccine developed by Oxford University and produced by AstraZeneca is so crucial to global efforts. The cost is a mere fraction of those of the other players and then for storage temperature, along with Russia’s Sputnik vaccine, it can be stored at common refrigerator temperatures. Both Pfizer’s and Moderna’s need to be kept chilled at temperatures beyond your common freezer.

And in terms of effectiveness, which is what we all really care about, they’re fairly similar, except for the Oxford University version. Oxford’s has an overall effectiveness of 70%. (In)famously, it exhibited a wide range of effectiveness during trials of between just over 60% and 90%.

The 60-odd% effectiveness was achieved when using the recommended dosage. However, in one small group of trial participants, they erroneously were given a half-dosage. And in that case, the dosage was found to be far more effective, approximately 90%. And this is why we would normally have longer, wider-ranging trials, to dial in things like doses. But, you know, pandemic and we’re trying to return to some sense of normalcy in a hurry.

All that said, Oxford’s will be crucial to the developing world, where incomes and government expenditures are lower and cold-storage infrastructure much less, well, developed. And we need to get this coronavirus under control globally, because if we don’t, the virus could persist in reservoirs, mutating for years until the right mutation comes along and the next pandemic sweeps across the globe.

I know we’re presently all fighting about wearing masks, but when we get to having vaccines available to the public, let’s really try to not make that a political issue.

Credit for the original piece goes to the BBC.

Credit for my piece goes to me.