The G7 conference in France wrapped up yesterday and they announced an aid package for Brazil. Why? Because satellite data from both Brazil and the United States points to a rash of fires devastating the Amazon rainforest, the world’s largest carbon sink, or sometimes known as the lungs of the Earth. I have not had time to check this statistic, but I read that 1/5 the world’s oxygen comes from the Amazon ecosystem. I imagine it is a large percentage given the area and the number of trees, but 20% seems high.

Regardless, it is on fire. Some is certainly caused by drier conditions and lightning strikes. But most is manmade. And so after the Brazilian president Jair Bolsonaro said his country did not have the resources to fight the fires, the G7 offered aid.

This morning, Bolsonaro refused it.

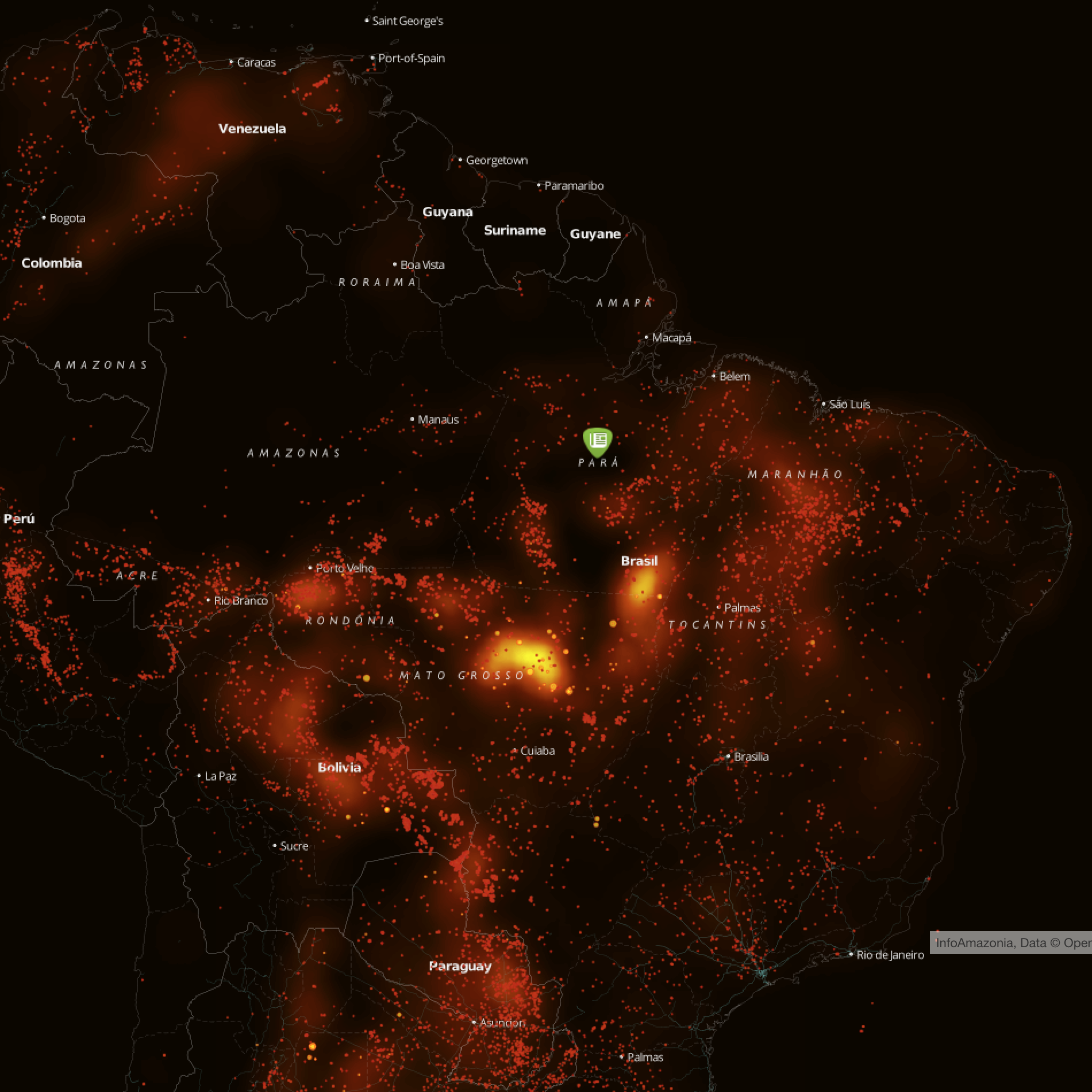

And so we have this map from InfoAmazonia that takes NASA data on observed fires for all of South America. I cropped my screencapture to Brazil.

A key feature to note here, in addition to that black background approach, is that you will see three distinct features: yellow hotspots fading to cold black areas, yellow dots with red outlines, and red dots. Each means something different. The yellow to red to black gradient simply means frequency of fires, the yellow dots with red outlines represent significantly hot fires from 2002 through 2014. The red dots are what concern us. Those are fires within the last month.

Sure enough, we see lots of fires breaking out across the Amazon. And Bolsonaro not only rejected the aid, but a few weeks ago he rejected similar data. He fired the head of a government agency tasked with tracking the deforestation of the Amazon after he released the agency’s monthly report detailing the deforestation. It had risen by 39%.

From a design standpoint, it is a solid piece. I do wonder, however, if some kind of toggle for the three datasets could have been added. Given the focus on the new fires breaking out, isolating those compared to the historic fires would be useful.

But before wrapping up, I also want to point out that there are a significant number of red dots appearing outside Brazil. The Amazon exists beyond borders, and there are a significant number of fires in neighbouring Bolivia and Paraguay. Let alone around the world…

Credit for the piece goes to InfoAmazonia.org.