Tag: Athletic

-

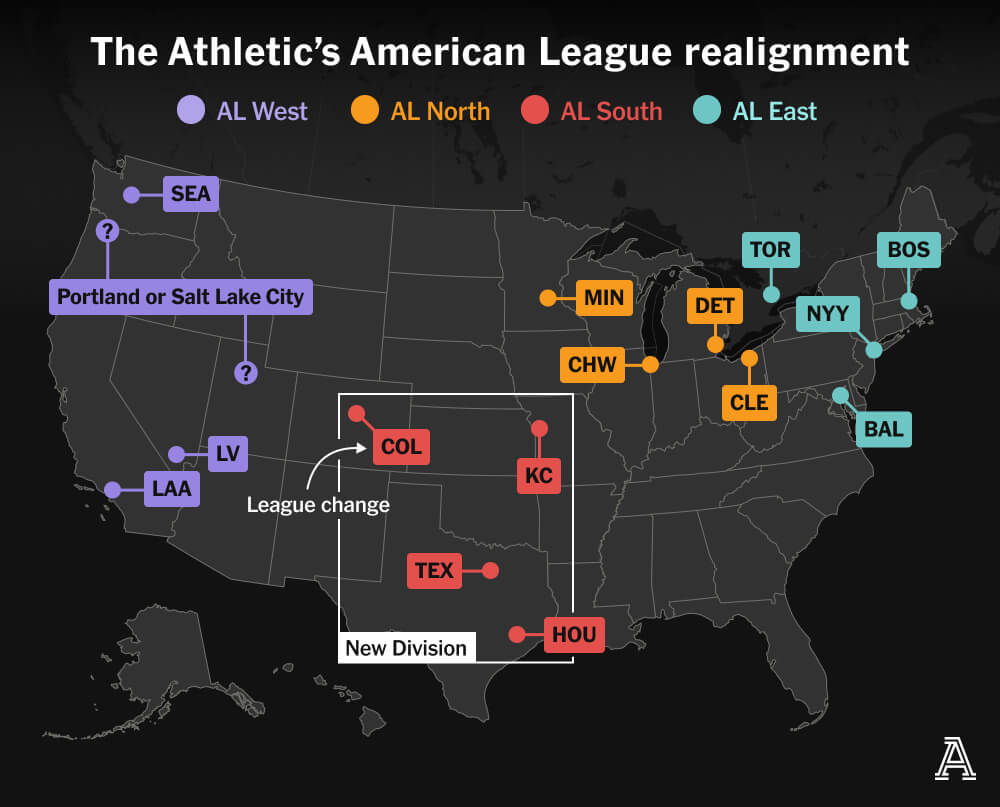

MLB’s Realignment

Last weekend, Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred created a mild furore when he discussed the sport’s looming expansion and how it would likely prompt a geographic realignment. I am old enough I still recall baseball’s two leagues—the American and National—organised into only two divisions—East and West. In the early 1990s, baseball expanded and created…

-

When Is a Torpedo Is Not a Torpedo?

When it’s a torpedo bat. Last week I looked at baseball’s new torpedo bats in a humourous light. But I did want to take a more serious look, because bat evolution has been part of the tale of baseball since its beginning. Back in the day bats featured long lengths and heavier weights. These days,…

-

Sankey Shows Starters Sticking with Sticky Stuff

I spent way more time trying to craft that title than I’d like to admit. Headline writing is not easy. Quick little piece today about Sankey diagrams. I love them. You often see them described as flow diagrams—this piece is in the article we’ll get to shortly—but they are more of a subset within a…