Tag: maps

-

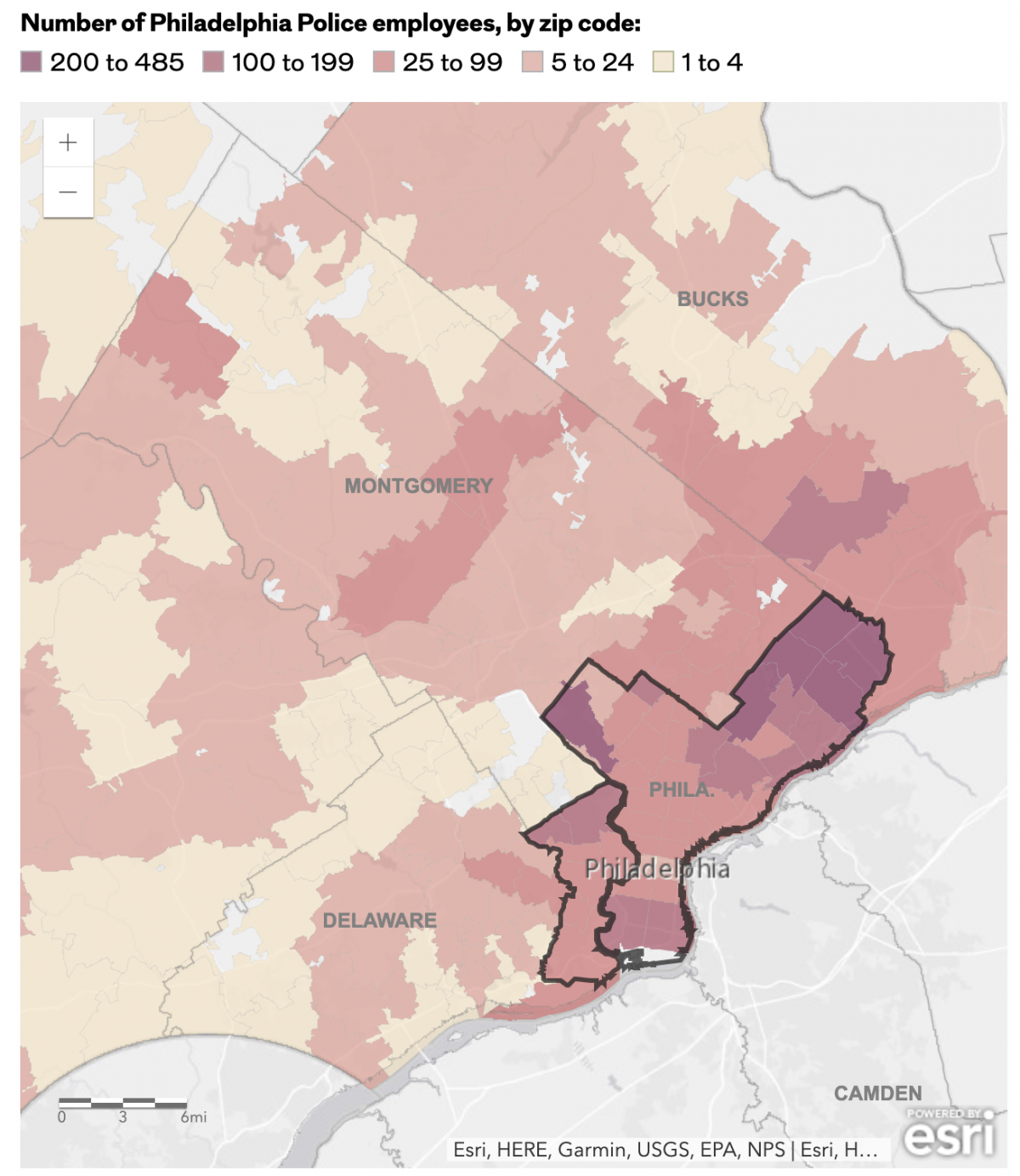

The Philadelphia Beat is Pretty Big

Early last week I read an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer about where the city’s police officers live, an important issue given the city’s loose requirement they reside within the city limits. Whilst most do, especially in the far Northeast, the Northwest, and South Philadelphia, a significant number live outside the city. (The city of…

-

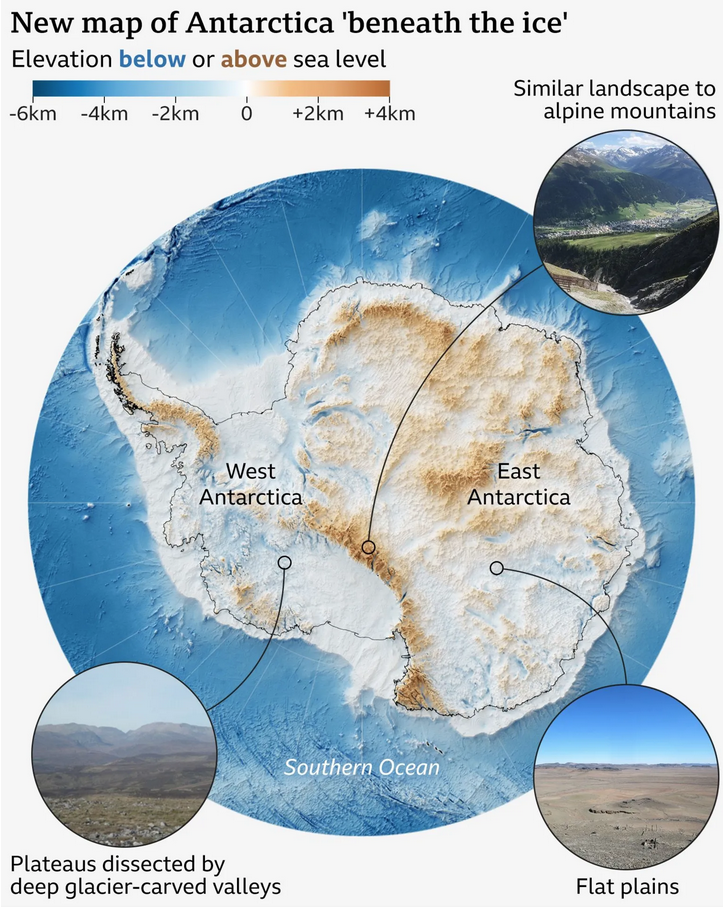

A View Beneath the Ice

I love maps. And above the ocean’s surface, we generally have accurate maps for Earth’s surface with only two notable exceptions. One is Greenland and its melting ice sheet is, in part, contributes to the emerging conflict between the United States and Denmark over the island’s future. The other? Antarctica. Parts of the East Antarctic…

-

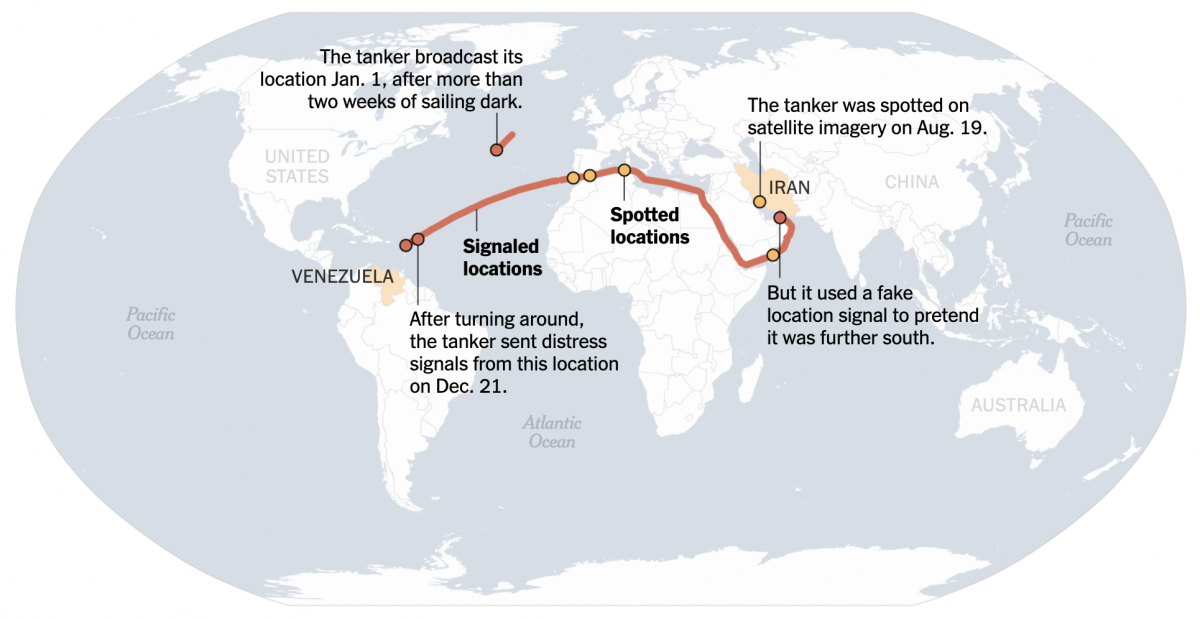

When the Ship Hits the Fan

On Friday I flagged this article from the New York Times for the first post in the new year here on Coffeespoons. The article discussed a Venezuelan oil tanker fleeing US Coast Guard and US Navy forces attempting to interdict the vessel as she steams into the North Atlantic. Whilst the article led with a…

-

Off on the Road to Rhode Island

Yesterday I read an article from the BBC about this weekend’s shooting at Brown University, one of the nation’s top universities. The graphic in question had nothing to do with killings or violence, but rather located Rhode Island for readers. And the graphic has been gnawing at me for the better part of a day.…

-

When the Walls Fell

Back in September I wrote about the siege of el-Fasher in Sudan, wherein the town and its government defenders faced the paramilitary rebel forces, the Rapid Support Force (RSF). At the time the RSF besiegers were constructing a wall to encircle the town and cut residents and defending forces off from resupply and reinforcements. At…

-

Philadelphia Blue Jays

Last weekend one of my good mates and I went out watch Game 7 of the World Series, wherein the Los Angeles Dodgers defeated the Toronto Blue Jays for Major League Baseball’s championship. Whilst we watched, I pointed out that the Jays’ pitcher at the moment hailed from a suburb of Philadelphia. He was well…

-

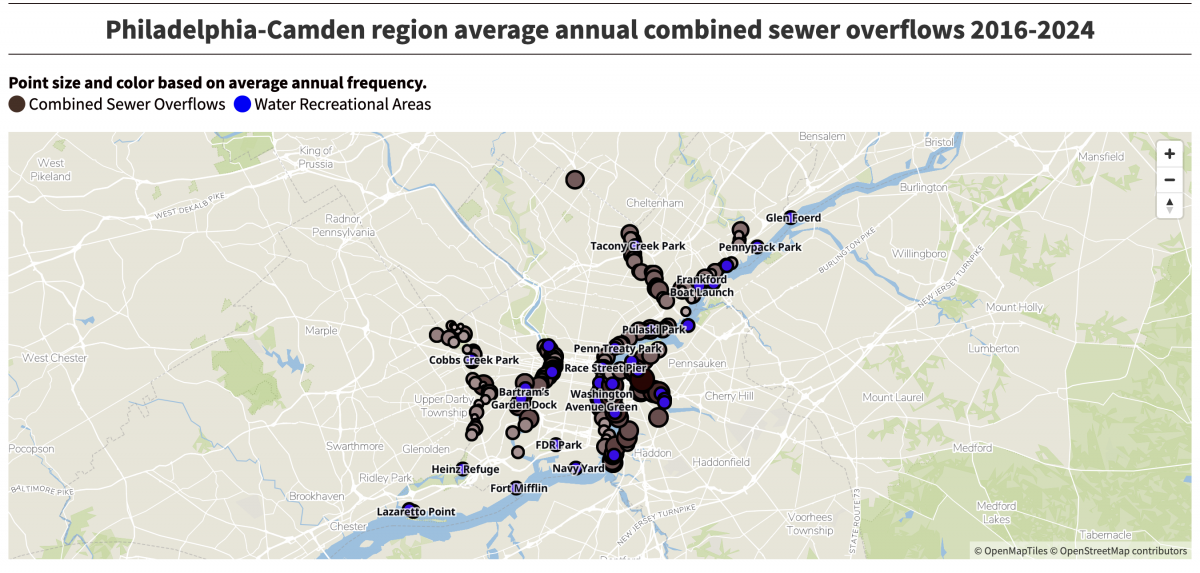

Boy, Does That Stink

(Editor’s note, i.e. my post-publish edit: The subject matter, not the work.) Last week the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article about the volume of sewage discharged into the region’s waterways over nearly a decade. It cited a report from Penn Environment, which claimed 12.7 billion tons of sewage enter the Delaware River’s watershed. I clicked…

-

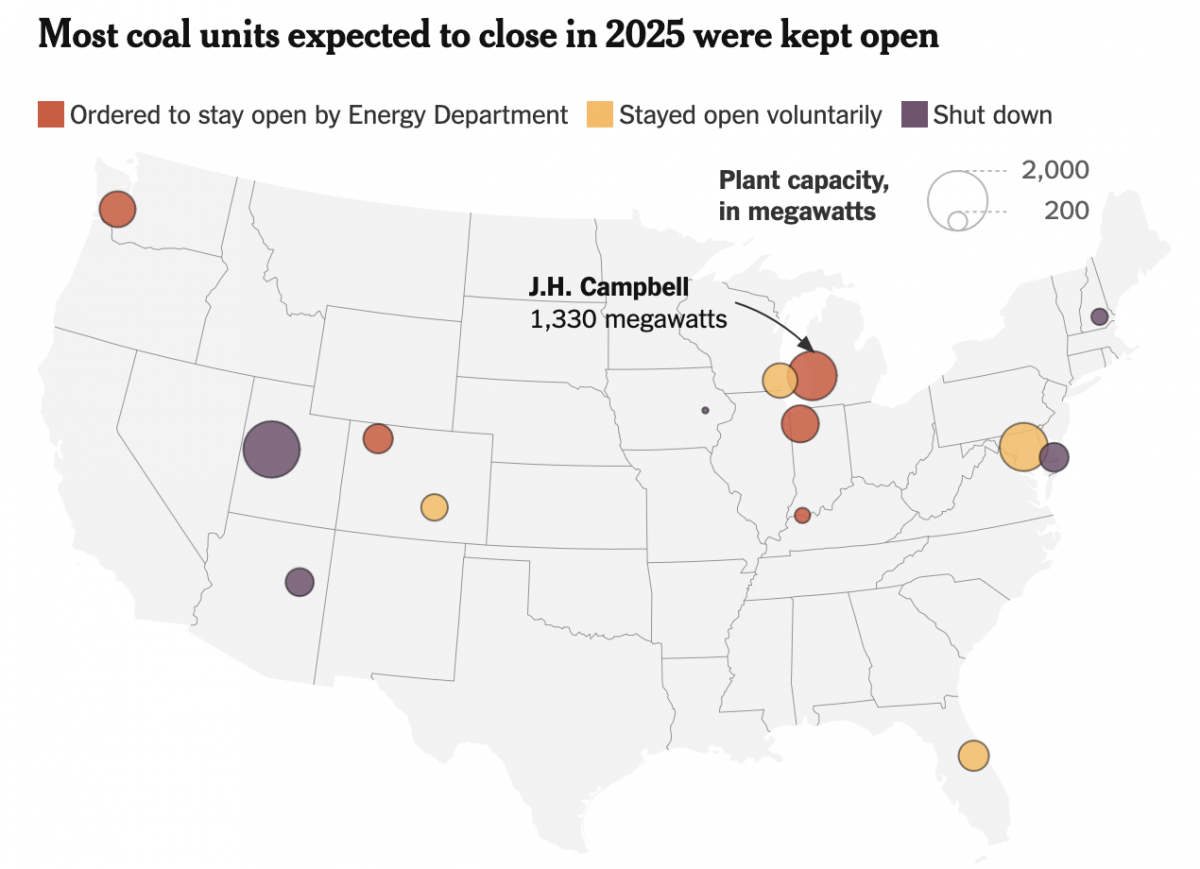

Where’s the Tin Can?

After a few weeks away for some much needed R&R, I returned to Philadelphia and began catching up on the news I missed over the last few weeks. (I generally try to make a point and stay away from news, social media, e-mail, &c.) One story I see still active is the US threatening Venezuela.…

-

Sharing a Coastline Between Friends

Another week has ended. Another weekend begins. I saw this a little while ago and flagged it for myself to share on a just for fun Friday. And since I posted a few things this week I figured I would share this as well. It is remarkable it took the similarity of the two coastlines…