Tag: baseball

-

Philadelphia Blue Jays

Last weekend one of my good mates and I went out watch Game 7 of the World Series, wherein the Los Angeles Dodgers defeated the Toronto Blue Jays for Major League Baseball’s championship. Whilst we watched, I pointed out that the Jays’ pitcher at the moment hailed from a suburb of Philadelphia. He was well…

-

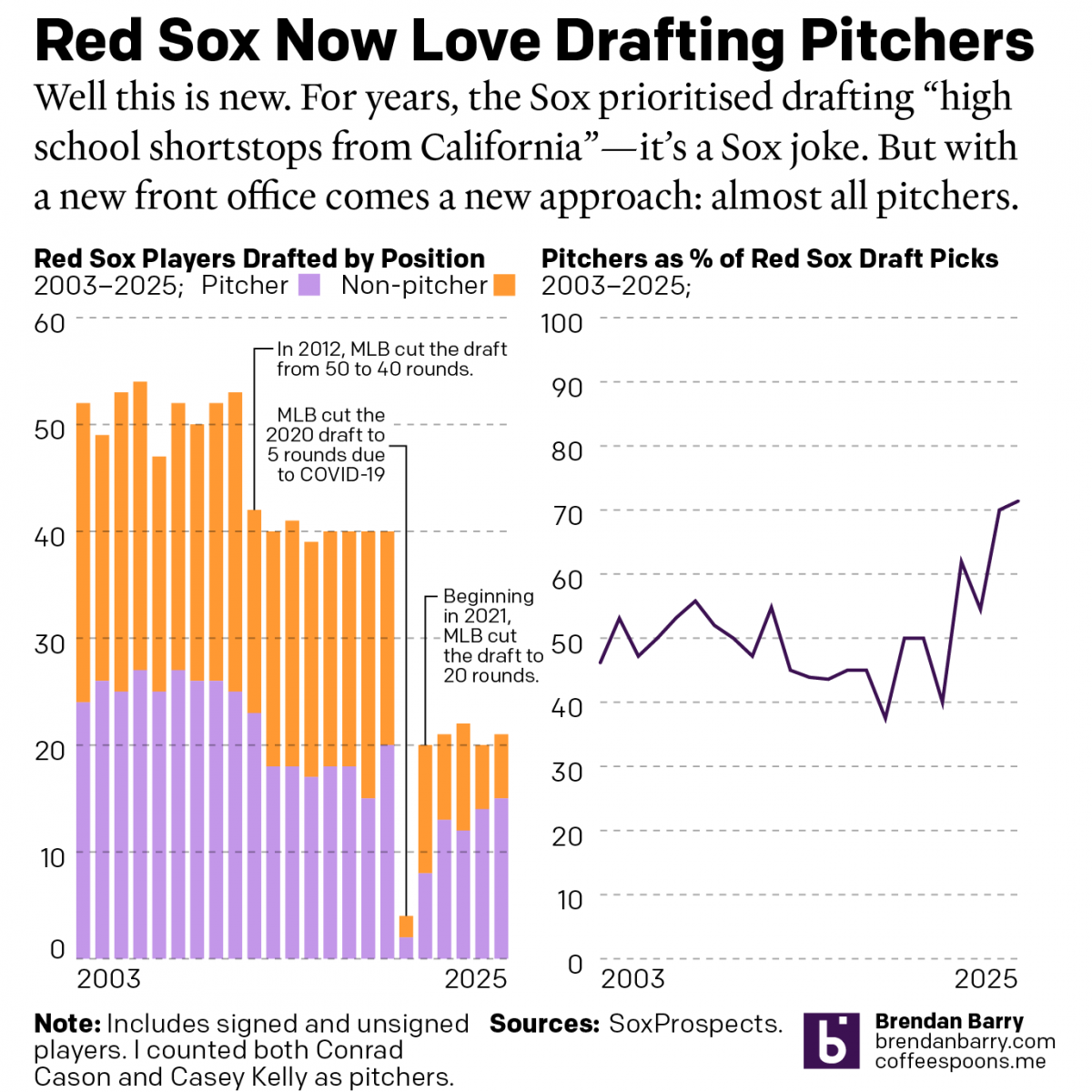

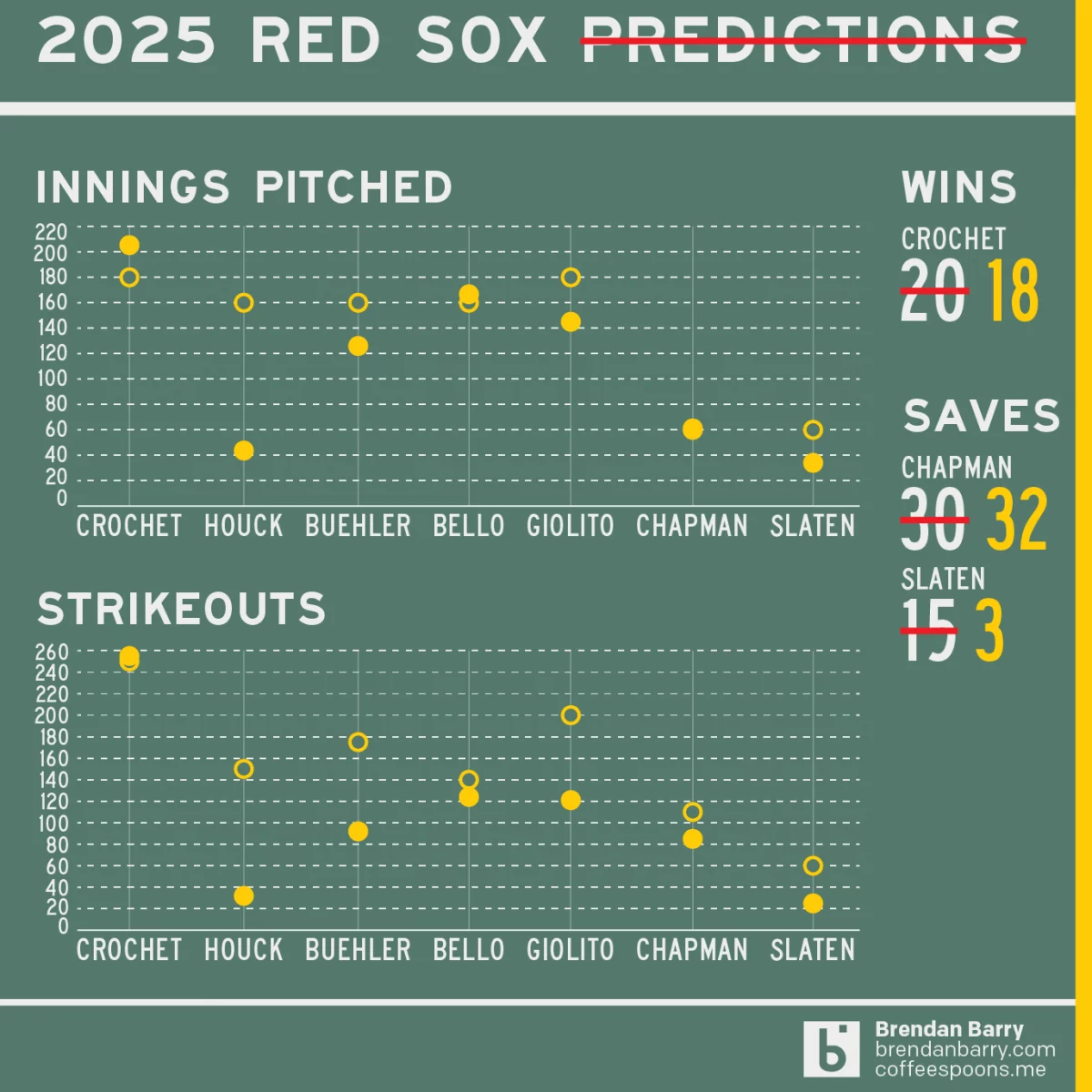

Revisiting My 2025 Red Sox Predictions

Back in March I posted my predictions for the 2025 Boston Red Sox on my social media feeds. I chose not to post it here, because the images had no real data visualisation and the only real information graphic was my prediction of the playoffs via a bracket. I did, however, write about how the…

-

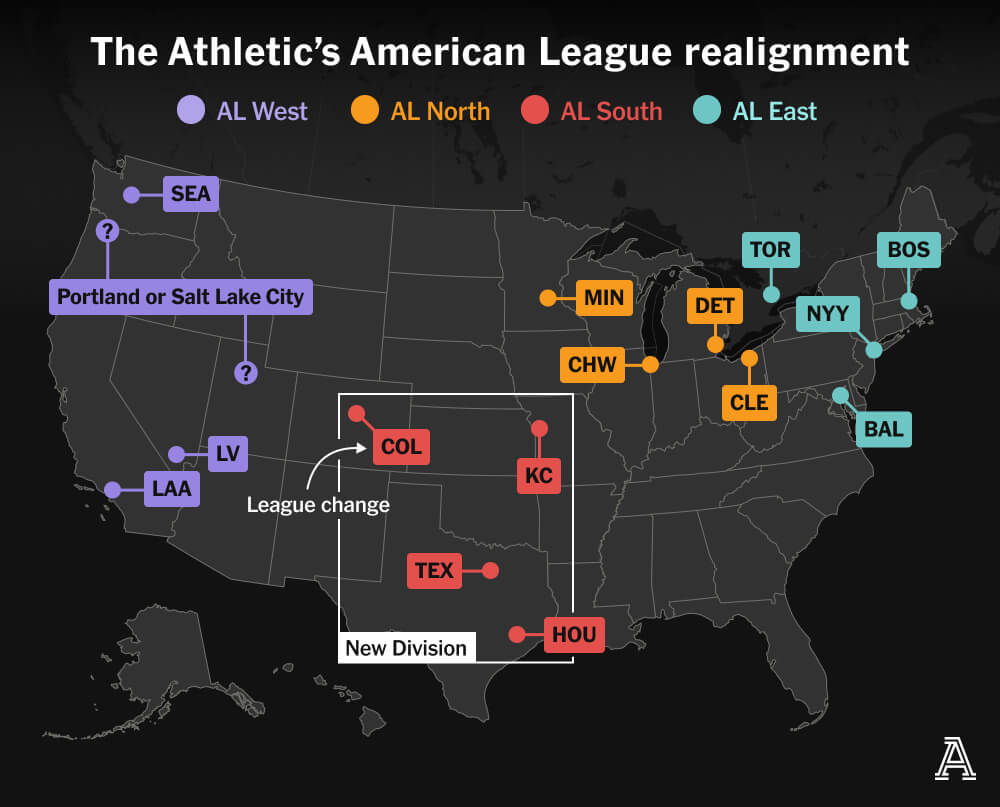

MLB’s Realignment

Last weekend, Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred created a mild furore when he discussed the sport’s looming expansion and how it would likely prompt a geographic realignment. I am old enough I still recall baseball’s two leagues—the American and National—organised into only two divisions—East and West. In the early 1990s, baseball expanded and created…

-

Bring on the Beantown Boys

For my longtime readers, you know that despite living in both Chicago and now Philadelphia, I am and have been since way back in 1999, a Boston Red Sox fan. And this week, the Carmine Hose make their biennial visit down I-95 to South Philadelphia. And I will be there in person to watch. This…

-

When Is a Torpedo Is Not a Torpedo?

When it’s a torpedo bat. Last week I looked at baseball’s new torpedo bats in a humourous light. But I did want to take a more serious look, because bat evolution has been part of the tale of baseball since its beginning. Back in the day bats featured long lengths and heavier weights. These days,…

-

Damn the Torpedoes!

Baseball is back and so bring forth the controversies. One of the ones from last week? The torpedo bat. To be clear, the torpedo bat has been around for a few years—it’s not new. However, on Opening Weekend, the Yankees beat up on Milwaukee Brewers’ pitching. But a Yankees announcer specifically pointed out the design…

-

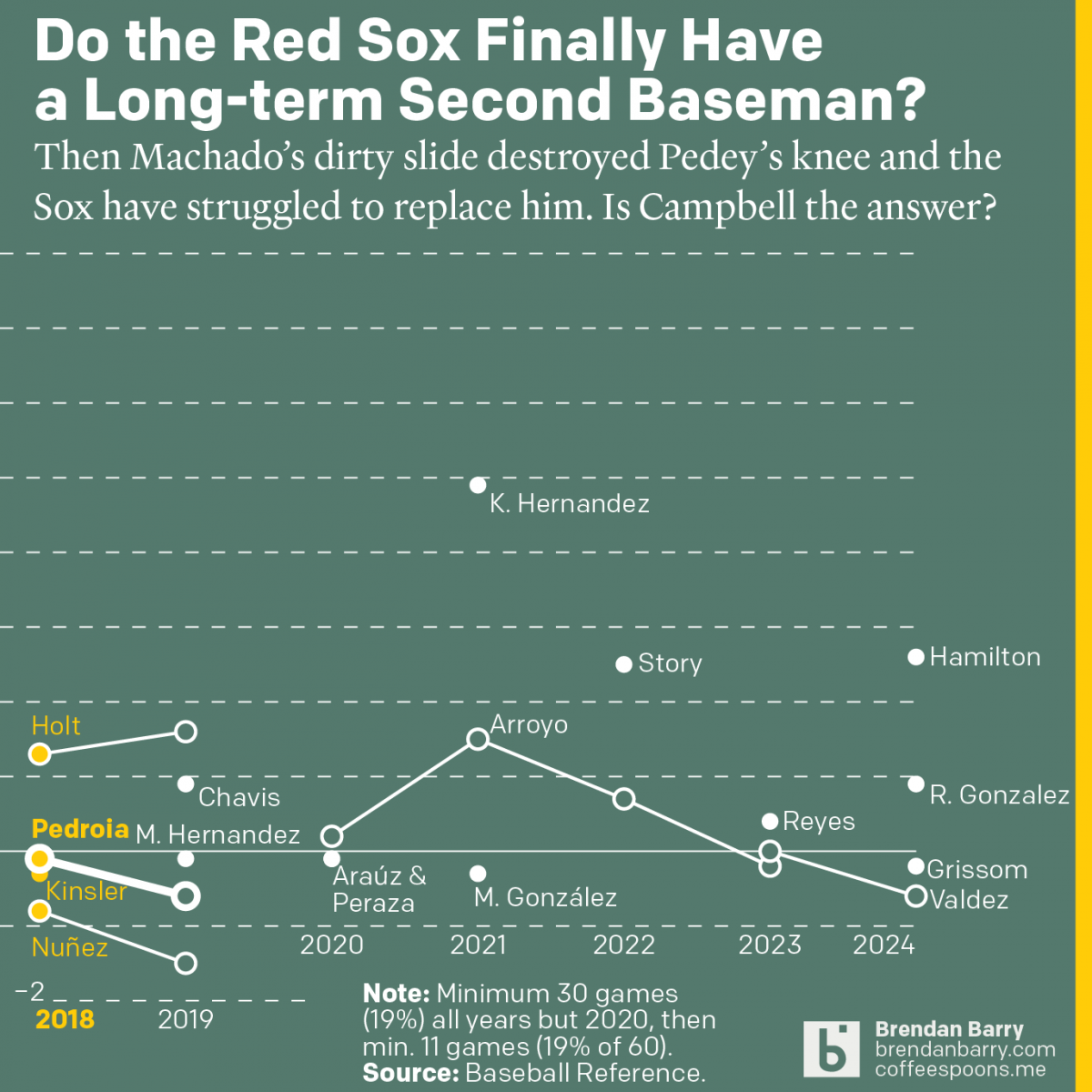

The Red Sox May Finally Have a Second Baseman

Last week was baseball’s opening day. And so on the socials I released my predictions for the season and then a look at the revolving door that has been the Red Sox and second base since 2017. Back in 2017 we were in the 11th year of Dustin Pedroia being the Sox’ star second baseman.…

-

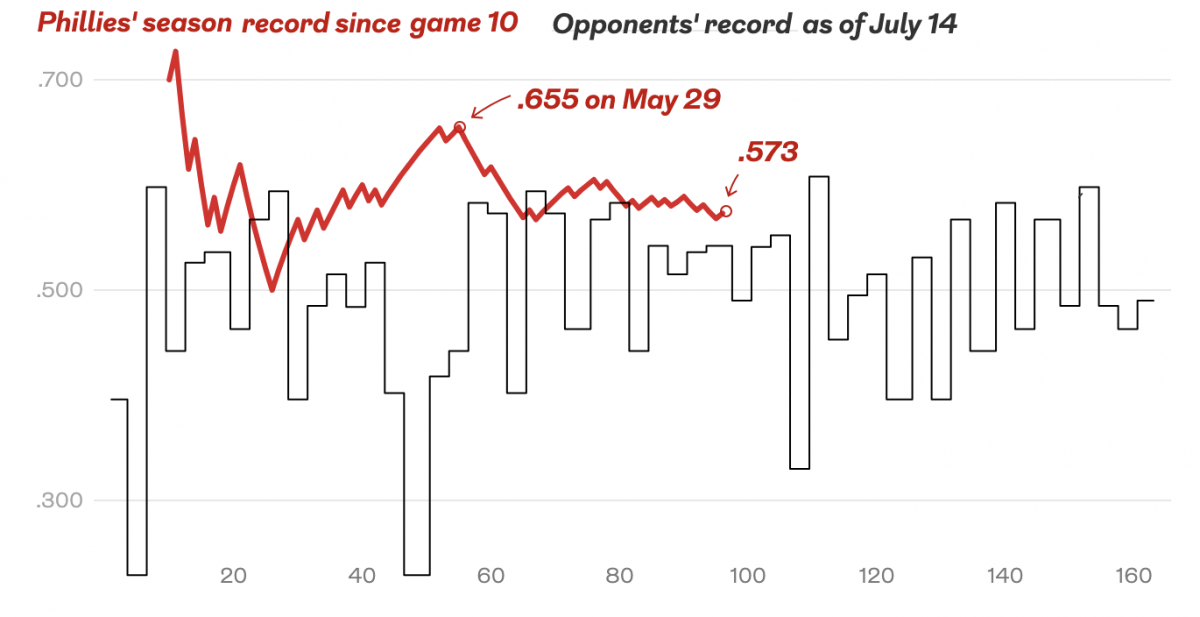

Predicting…the Known Stats?

I have been trying to post more regularly here on Coffeespoons, but now that baseball’s postseason is in full swing—pun fully intended—my free time is spent watching balls and strikes at all hours of the day. (Though, with the Wild Card round over and the move from four to two games per day, my time…

-

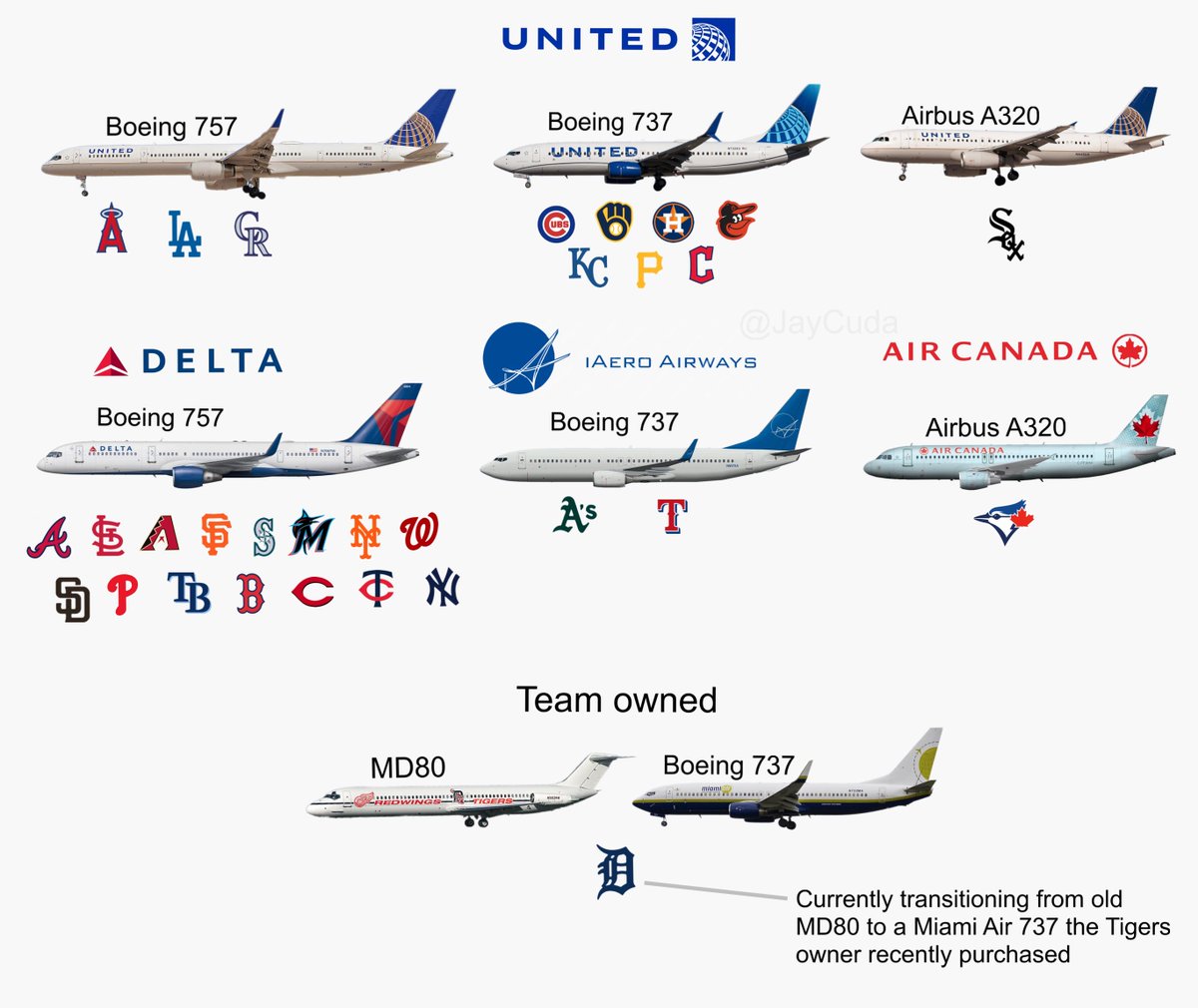

Tired of These Motherf*cking Sox on This Motherf*cking Plane

At least, that’s what I imagine South Siders saying in Chicago as they watch the White Sox team charter plane land at Midway. For those not following America’s Major League Baseball season, the Chicago White Sox are one of two clubs claiming Chicago as their home. (The other being the Cubs.) And the White Sox—not…