It’s cool. In the darkness of space.

We made it to the end of the week, a big week for space news.

So with that, enjoy this illustration from xkcd about the James Webb Space Telescope.

Credit for the piece goes to Randall Munroe.

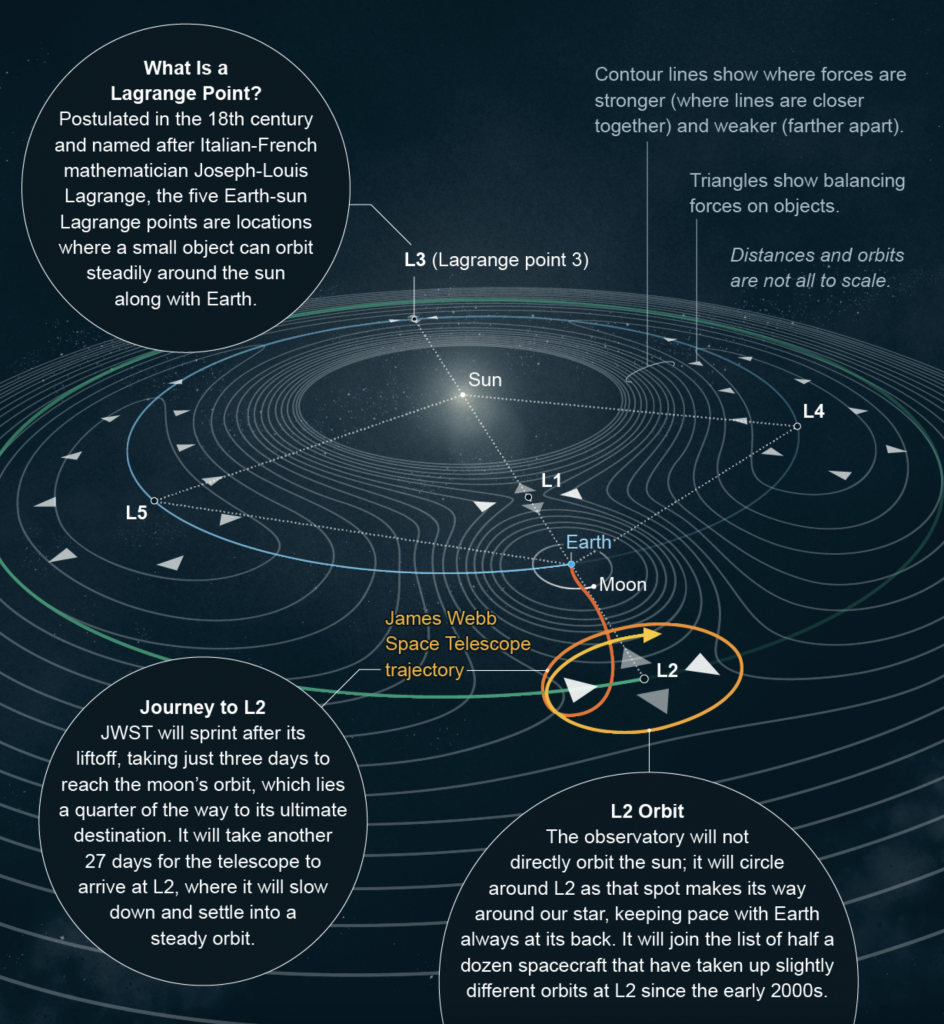

Yesterday I received a question about where the new James Webb Space Telescope is located. Is it in orbit of the Earth, like Hubble? Is it out in deep space?

The answer is no, not really. Now I spent this morning trying to illustrate the answer to that question myself. However, it’s taking me too long. So we’re going to reference this great illustration from Scientific American.

James Webb orbits around a point called the L2 Lagrange point, which sits in a line with Earth and the Sun. The telescope points out and away from the sun whilst the sun shield keeps the sunlight from warming the spacecraft while solar panels collect said light and power the spacecraft.

So if any of my other readers had a similar question, hopefully this goes some ways to answering the question.

Credit for the piece goes to Michael Twombly.

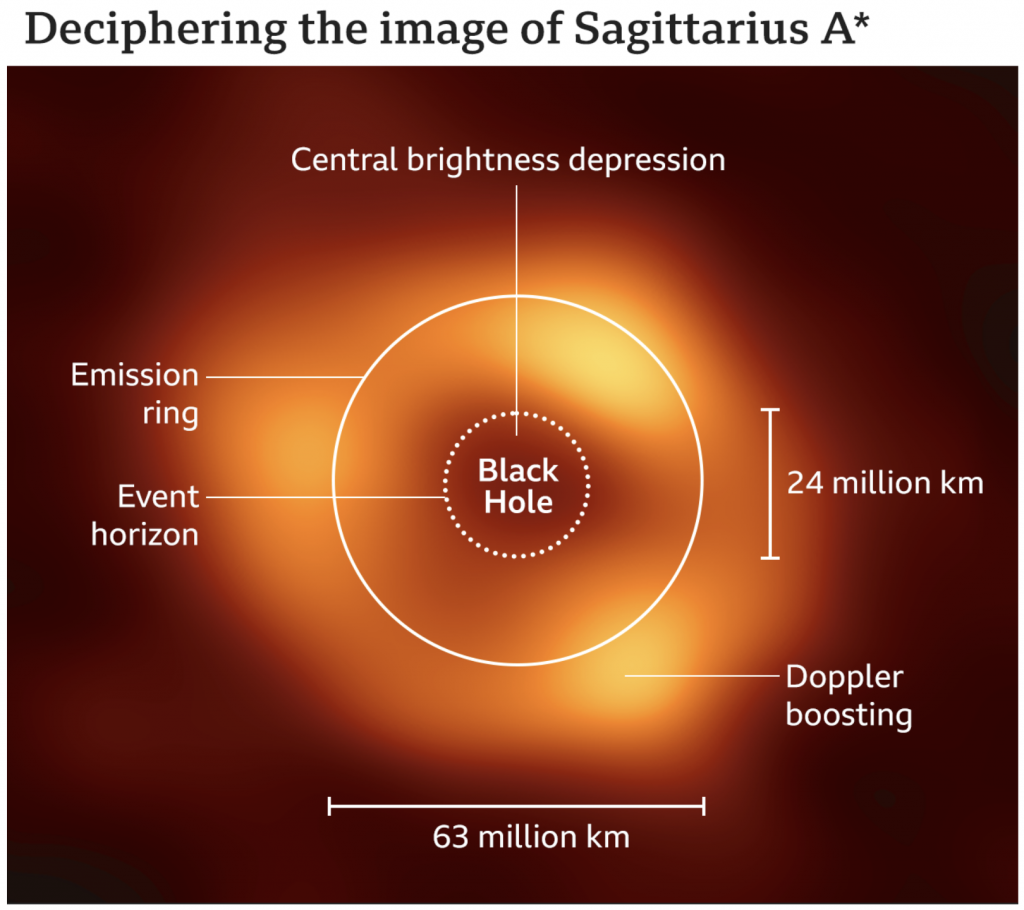

Two years ago I posted about how the Event Horizon Telescope Collaboration managed to take the first photograph of a black hole, in particular a supermassive black hole at the centre of the M87 galaxy, one of those galaxies far, far away that we see at a long time ago.

This morning, the same group of scientists released the first photograph of Sagittarius A*, the supermassive black hole at the centre of our very own Milky Way Galaxy. The BBC article I read this morning included the photo of the black hole, which you should definitely check out because of its importance in the history of astronomy. But, for our purposes here on Coffeespoons, I wanted to look at the diagram the designers at the BBC made to explain the photograph.

The designer used some simple white lines with a thicker stroke for the axis and defining features and a thinner line to point to elements of the photo. In particular I like the dotted line for the black hole, because there is no real way to photograph the hole itself since it consumes all the light we would need to image it. Instead, we photograph the “black hole” at the centre of the accretion disk, all the super heated gas and matter slowly swirling around and collapsing into the singularity. We also get two axes to show the size of the ring and that of the black hole itself. The ring measures a diameter of about 63 million kilometres. The distance from the Sun to Mercury, the closest planet to our Sun, is 58 million kilometres.

Supermassive indeed.

Well done, science. Well done.

Credit for the piece goes to the graphics team at the BBC.

Happy Friday, everyone.

At the beginning of the week, we looked at the launch and deployment of the new James Webb telescope. If you recall, one of the key elements of the satellite’s design is its sunshield. As the name says, it shields the satellite from the sun, thus keeping the equipment super cold, which is necessary to operate in the range of infrared.

But, as xkcd points out, that’s not actually the real reason for the sunshield.

Credit for the piece goes to Randall Munroe.

We’re back after a nice holiday break. And one of the most fascinating things to happen was the successful—and seemingly easy, more on that in a bit—launch of the James Webb space telescope. The James Webb was developed by NASA with contributions from both the European Space Agency (ESA) and the Canadian Space Agency (CSA). Whilst it did launch behind schedule and at a price tag of $10 billion, the James Webb is the most sophisticated and complex space telescope mankind has yet launched into space. It will look backwards into time to some of the earliest stars and galaxies in the universe. It will also look at the thousands of exoplanets we have discovered in the last three decades. The instruments aboard James Webb will be able to help us identify if any of these planets have water and other ingredients necessary for life as we know it. This could be one of the most monumental space missions yet.

But James Webb’s launch was far from guaranteed. As this great article from the BBC explains, the construction, assembly, launch, and deployment were all incredibly complicated. James Webb is expected to operate for ten years before its fuel, needed to keep the telescope cold, runs out. However, the seemingly easy launch and deployment means that it used less fuel than expected. Some early reports suggest that the telescope may have some additional time left in it now before the fuel runs dry.

I encourage you to read the article, because it explains the advantages of the telescope, how it works, and its deployment with several illustrations. There are five in particular, though I’ll share only two screenshots.

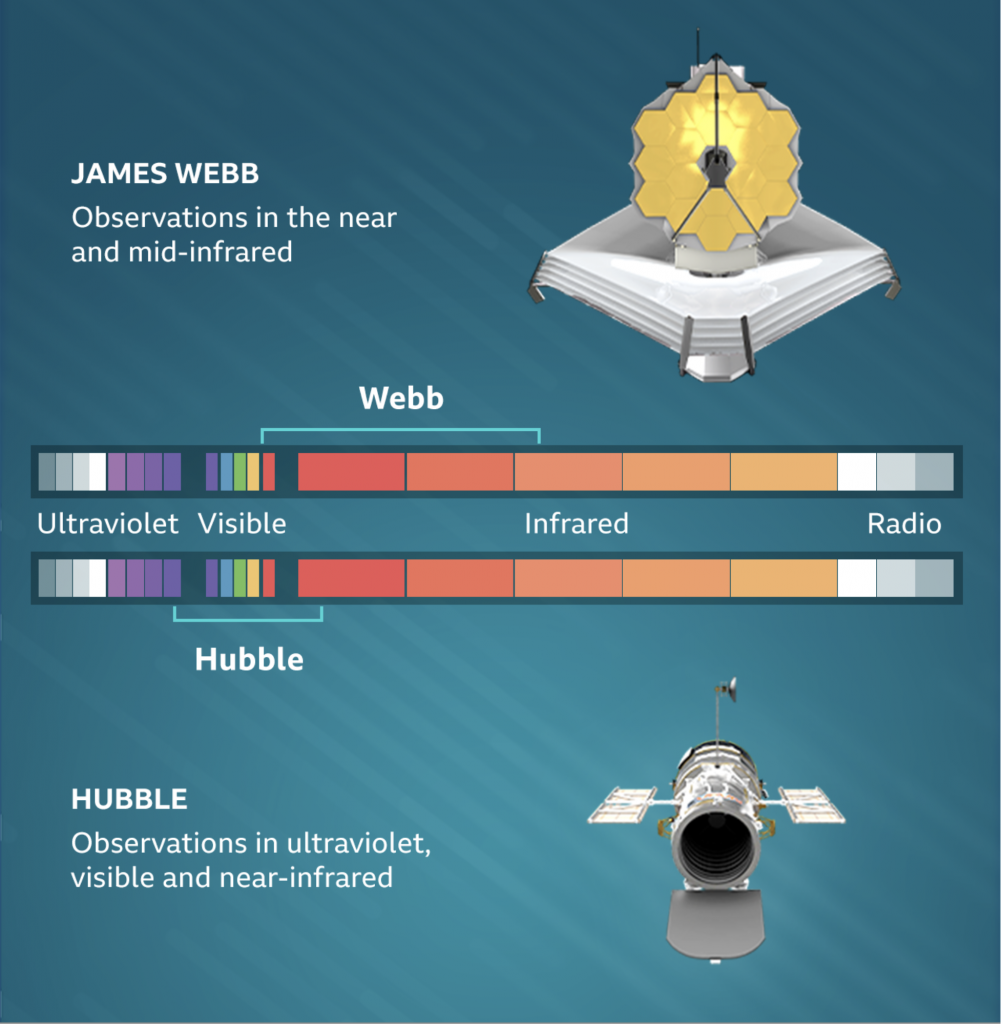

The most important is this, the key distinction between Hubble and James Webb. It shows how the two space telescopes will be operating in different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum.

The graphic fakes the colours, because by definition we can only see the visible portions of the spectrum. Wavelengths get either too short or too long on either side of the visible spectrum—which differs for different species. I would actually really enjoy seeing how these two spectra stack up against other space observatories like Chandra (x-ray) and Spitzer (infrared).

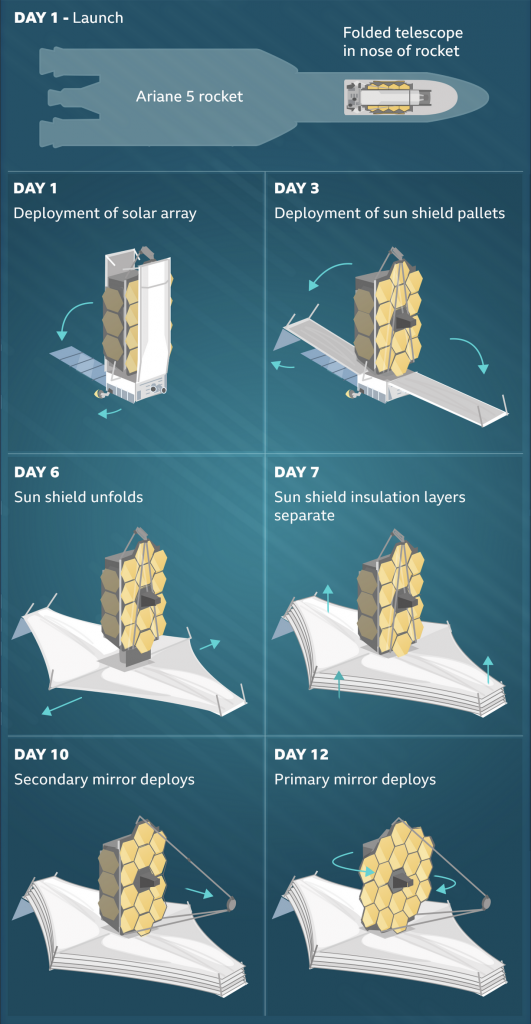

Next we have the deployment, which finished just last week. The graphic summarises how complicated this process was—and how fraught with risk. But in the end it went off without any major hitch.

This uses a nice series of small multiples of illustrations. These simplified drawings show how the tightly packed telescope unfolds and then begins deploying its vital heat shield then its mirror.

The last thing to check out in the article is a slider showing the “before” and “after”. You have seen them before for things like flood or hurricane damages. Here, however, you can compare a photo in Hubble’s visible light to an existing infrared version of the same photo.

Of course, just because the telescope finished deploying its mirror last week doesn’t mean we get photos this week. The Baltimore-based team running the observatory will spend the next few months tuning everything up. But the goal is hopefully to have the first images from James Webb sometime in June.

And then we have the next ten years to hopefully start collecting data.

Credit for the piece goes to the BBC graphics team.

Of course the inside threat are those little bodies of coronavirus causing Covid-19. We cover them a lot here. But there are also threats from little bodies outside, way outside. Like asteroids impacting us. And that was the news yesterday when NASA announced improved data from a mission to the asteroid Bennu allowed it to refine its orbital model.

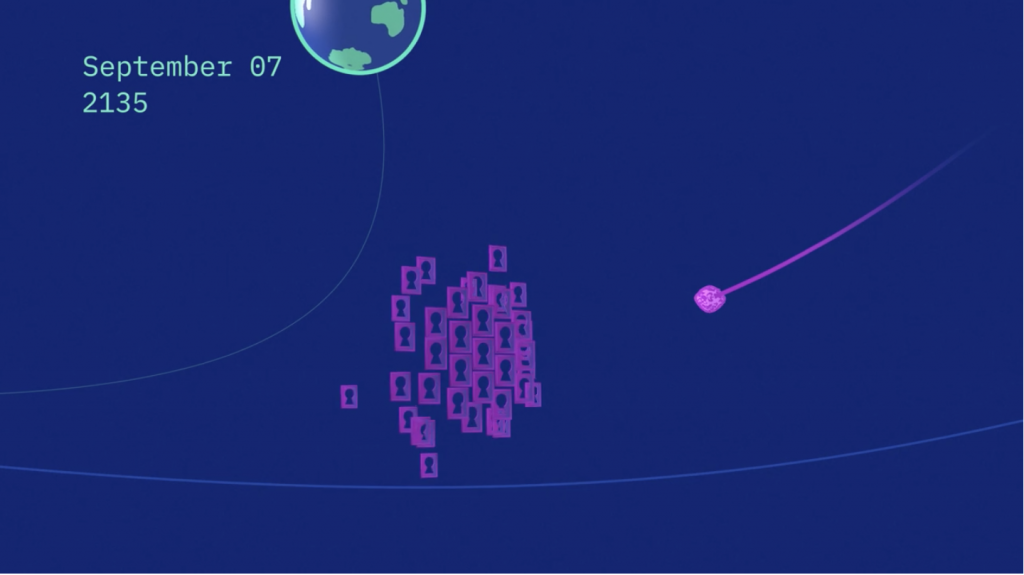

And we have reason to ever just so very slightly worry. Because there is a very slight chance that Bennu will impact Earth. In 2182. The New York Times article where I read the news included a motion graphic produced by NASA to explain that the determining factor will be a near pass in 2135.

Essentially, the exact course Bennu takes as it passes Earth in 2135 will determine its path in 2182. But just a few slight variations could send it colliding into Earth. Though, to be clear, it’s only a 1-in-1750 chance.

NASA used the metaphor of keyholes to explain the concept. The potential orbits in 2135 function as keyholes and should Bennu pass into the right keyhole, it will setup a collision with Earth in 2182. Hence the use of little keyholes in the motion graphic that accompanied the article.

But who knows, if we’re lucky the United Federation of Planets will still be formed in 2161 and the starship Enterprise will gently nudge Bennu back into a non-threatening orbit.

Credit for the piece goes to NASA.

When I was in high school, the United States would regularly spend space shuttles into orbit to help build this new thing: the International Space Station (ISS). In the aftermath of the Cold War, the nations of the world joined together to commit to building an orbital space station.

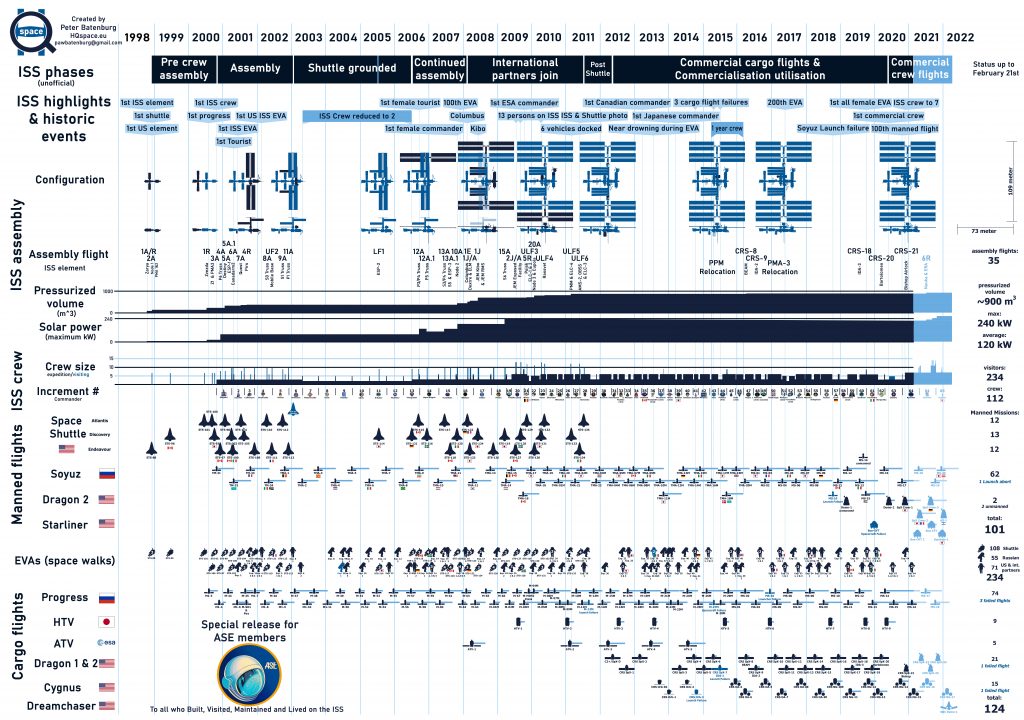

There was of course a time before the ISS, and I can recall many jokes being made about Mir, the Soviet then Russian space station. And before Mir there were other, though none as long-lasting. But I digress, we’re here today because recently Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield tweeted a graphic made by Peter Batenburg that visually captures the history of the International Space Station.

I think my favourite element is the graphical representation of the expansion of the ISS in terms of its volume. I’ve seen similar sort of graphics showing the addition of modules and new components, but I can’t recall seeing the amount of space where people can live and work being captured.

But really, the whole piece is worthy of sitting down and enjoying. After all the ISS is only about 22 years old. But there are questions of how much longer it will remain in orbit. I’m not aware of any concrete plans to fund it beyond 2030 nor any plans for an eventual replacement.

We can only hope that the ISS and its successor remain an area that fosters international cooperation for the next thirty years.

Credit for the piece goes to Peter Batenburg.

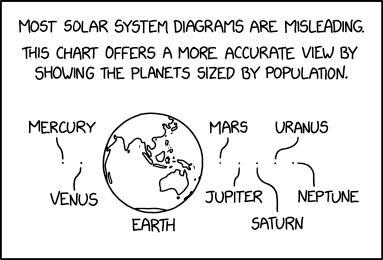

Damn you Neil deGrasse Tyson (but not really though)!

Because, you know, he advocated for de-planet-fying Pluto back in the oughts.

Which I mention because of this post from xkcd, which corrects common images of planets in the solar system accounting for their population.

Credit for the piece goes to Randall Munroe.

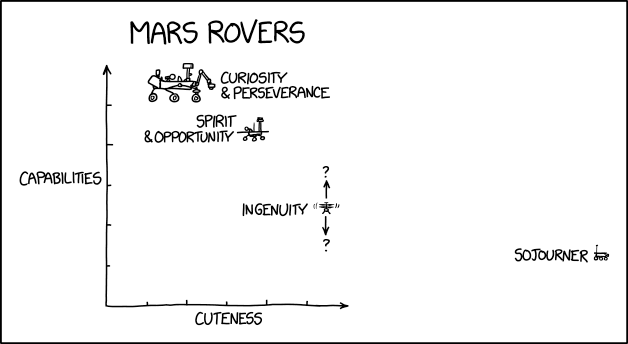

Perseverance landed on Mars on 18 February, almost a month ago. The video and photography the rover has already sent back has been stunning. We all know she is the most capable rover yet landed on the Red Planet, but what we all want to know is how cute is Perseverance compared to her predecessors?

Thankfully for that we have xkcd.

Credit for the piece goes to Randall Munroe.