Whenever someone not named Eovaldi or Perez starts a Red Sox game in 2020, that’s when.

We all know the Red Sox are the worst team in the American League. They have only two starters, maybe sometimes a third. And then the last two days of the regular five-day rotation cycle, manager Ron Roenicke throws some relievers at the wall and sees which ones stick that night. Spoiler: Few do.

But as much as I enjoy listening to the three-man broadcasting booth (Remy and Eck make the games fun to at least listen to) the games are unwatchable. And then to hear them try and dress a game up as having an opener? Well, what is the opener?

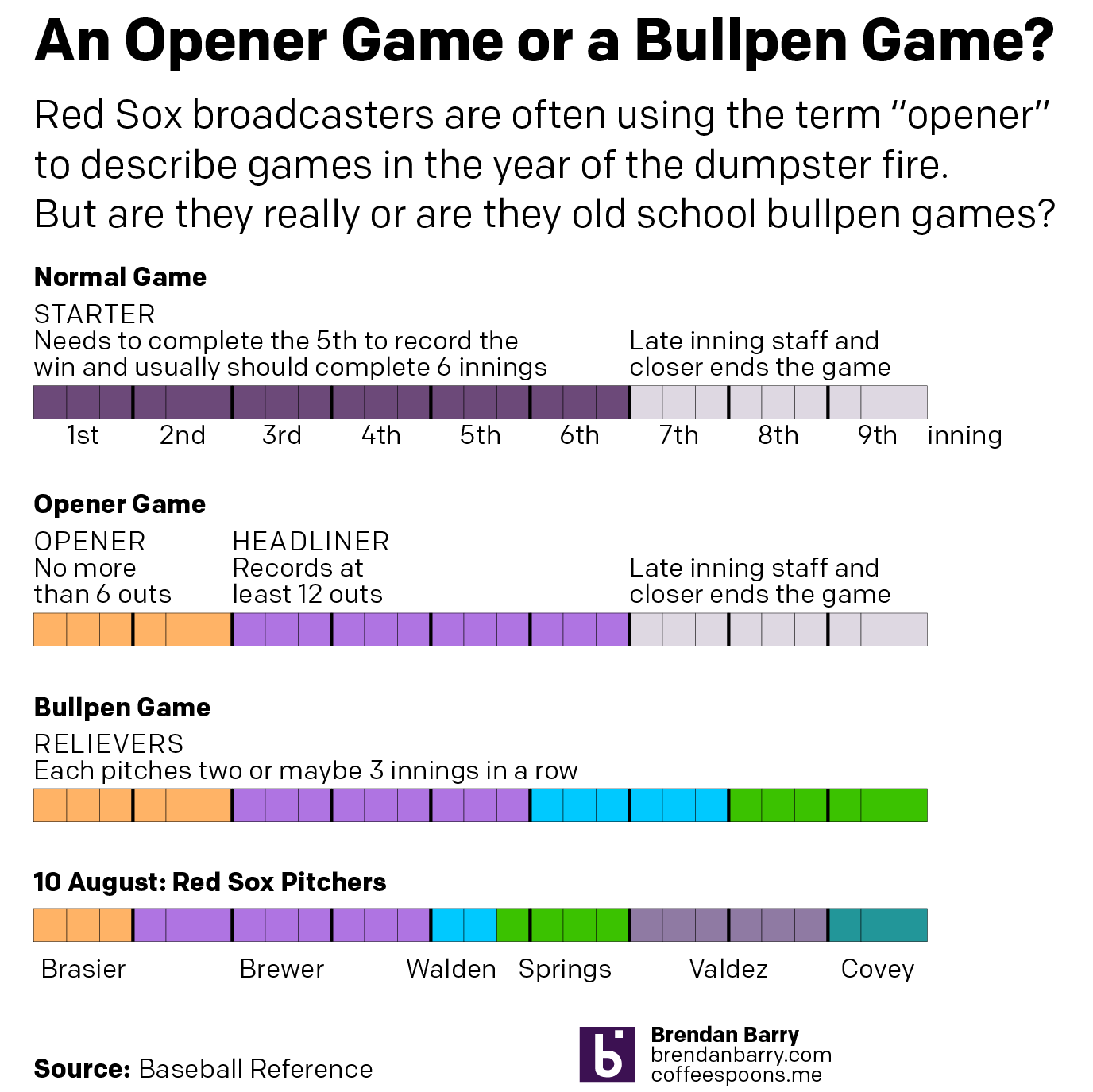

For the non-baseball fans, most are probably aware enough that some guy goes out to a small hill and throws (pitches) a ball at a batter for most of the night. Then towards the end, when the guy’s energy wanes, he is replaced by some guy who throws really fast. That’s over simplified, but that’s a normal ballgame. A starting pitcher records five, but ideally at least six, innings of work before handing the ball over to an eighth-inning setup man and then a ninth-inning closer. Sometimes a really good seventh-inning reliever sets up the setup man.

A bullpen game, by contrast, is when a bunch of those relief pitchers handle the entire game. Usually this would be after a game went into extra innings (since baseball cannot end in a tie, unless you’re in an All Star game), and the next day’s starting pitcher had to finish the long game by pitching several innings. With nobody available to throw six innings, a bunch of relievers come in and try to cover that by pitching one, two, or three innings each.

The opener game is relatively new. The idea is in addition to the really good closer, a really good opener records the first inning or two (3–6 outs) to deal with the opposing team’s best hitters. He then hands the ball over to a mediocre starting pitcher who throws the next four or five innings, who then hands the ball over to the late-inning relief specialists. Doing it this way, the starter avoids one set of at-bats or plate appearances by the opposition’s best hitters.

But when is an opener just a bullpen game? Well, it’s when that mediocre starting pitcher isn’t really a starting pitcher. And when he doesn’t even throw four or five innings. Basically all the Red Sox games this year.

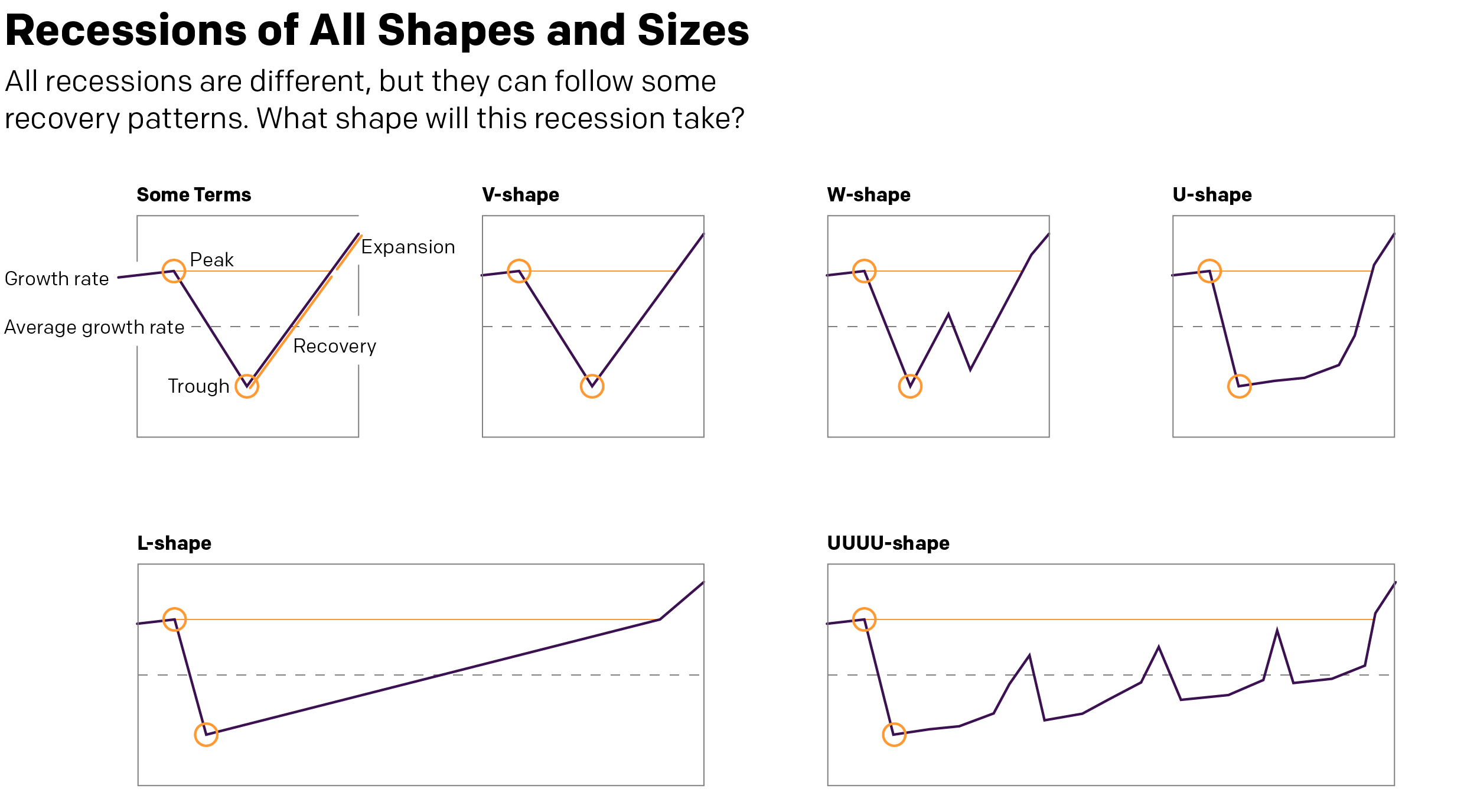

I made a graphic this morning to contrast those different types of games and compare them to a game I watched two nights ago between the Red Sox and the Tampa Bay Rays. The game was teed up as an opener with a good relief pitcher by the name of Ryan Brasier starting the first inning. But then instead of a mediocre starter pitching four or five innings, we got a mediocre reliever pitching three innings. He handed it over to a guy who was supposed to go maybe two, but couldn’t get through his second inning. He handed it over to another guy, who handed it over to another guy, who handed it over to a final guy. And none of those last guys were the good relievers you would typically expect to see. (Though, to be fair, the Sox weren’t winning, so why use your best relievers?)

Credit for the piece is mine.

Credit for the Red Sox dumpster fire of a season goes to John Henry and ownership.