I work in the field of graphic design—or visual communications design for those of you younger whippersnappers. Regardless of what you call it, the field itself generally did not become a discipline until the early parts of the 20th century. Obviously, painters and illustrators were performing many of the tasks in the 19th century and before then. But design comes from art, from painting and drawing. How old are those?

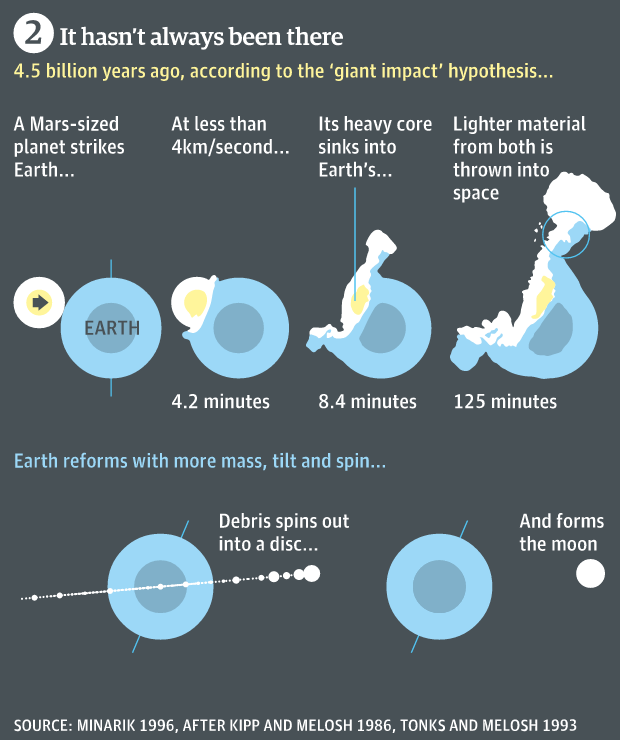

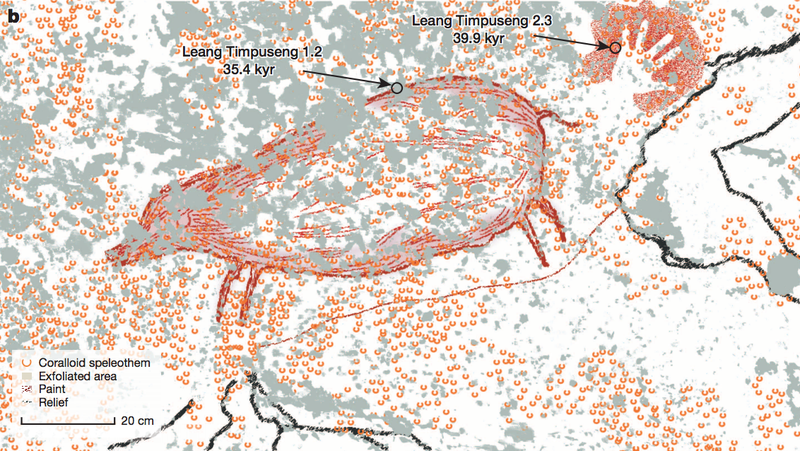

Well recent discoveries have just pointed to some really old paintings in Indonesia that rival the ages of what we already know in the cave paintings in France. The significance is that this means art likely did not spread from Europe to Asia as once thought. It either developed independently or stems from an earlier African ancestry. For the purposes of this blog, the writeup I found included an illustration of how these dates were determined.

Credit for the piece goes to the original authors of the Nature report.