Examining How We Measure Our Lives

Commentary, critiques, and observations on information design and data visualisation

-

The Pandemic’s Influence on Home Design

Read on…: The Pandemic’s Influence on Home DesignI took last week off for the Orthodox Easter holiday. But I am back now. For some of the time I was away, I stayed at an old stone farmhouse that the owners renovated into a short-term rental. That made me think about what I would want or need in my own space. Of course […]

-

Waiting for the Family Tree

Read on…: Waiting for the Family TreeI spent the past weekend in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania on a brief holiday to go watch some minor league baseball. That explains the lack of posting the last few days. (Housekeeping note, this coming weekend is Orthodox Easter, so I’ll be on holiday for that as well.) Whilst in Harrisburg I did other things besides watch […]

-

Where Are We?

Read on…: Where Are We?It’s been another week. And that’s why I thought of this post from Indexed last week. It seems to adequately describe where are at in this crazy world. But we all made it, so happy weekend, everyone. Credit for the piece goes to Jessica Hagy.

-

The B-52s

Read on…: The B-52sNot the band, but the long-range strategic bomber employed by the United States Air Force. This isn’t strictly related to Ukraine, but it’s military adjacent if you will. I thought about creating a graphic a few years ago to celebrate the longevity of the B-52 Stratofortress, more commonly called the BUFF, Big Ugly Fat Fucker. […]

-

Battalion Tactical Groups

Read on…: Battalion Tactical GroupsAs Russia redeploys its forces in and around Ukraine, you can expect to hear more about how they are attempting to reconstitute their battalion tactical groups. But what exactly is a battalion tactical group? Recently in Russia, the army has been reorganised increasingly away from regiments and divisions and towards smaller, more integrated units that […]

-

Keeping Things in Scale

Read on…: Keeping Things in ScaleAnother week of amazing, happy, awesome news. So let’s keep it all in perspective with this graphic from xkcd. We all made it to Friday, so enjoy your weekend, everyone. Credit for the piece goes to Randall Munroe.

-

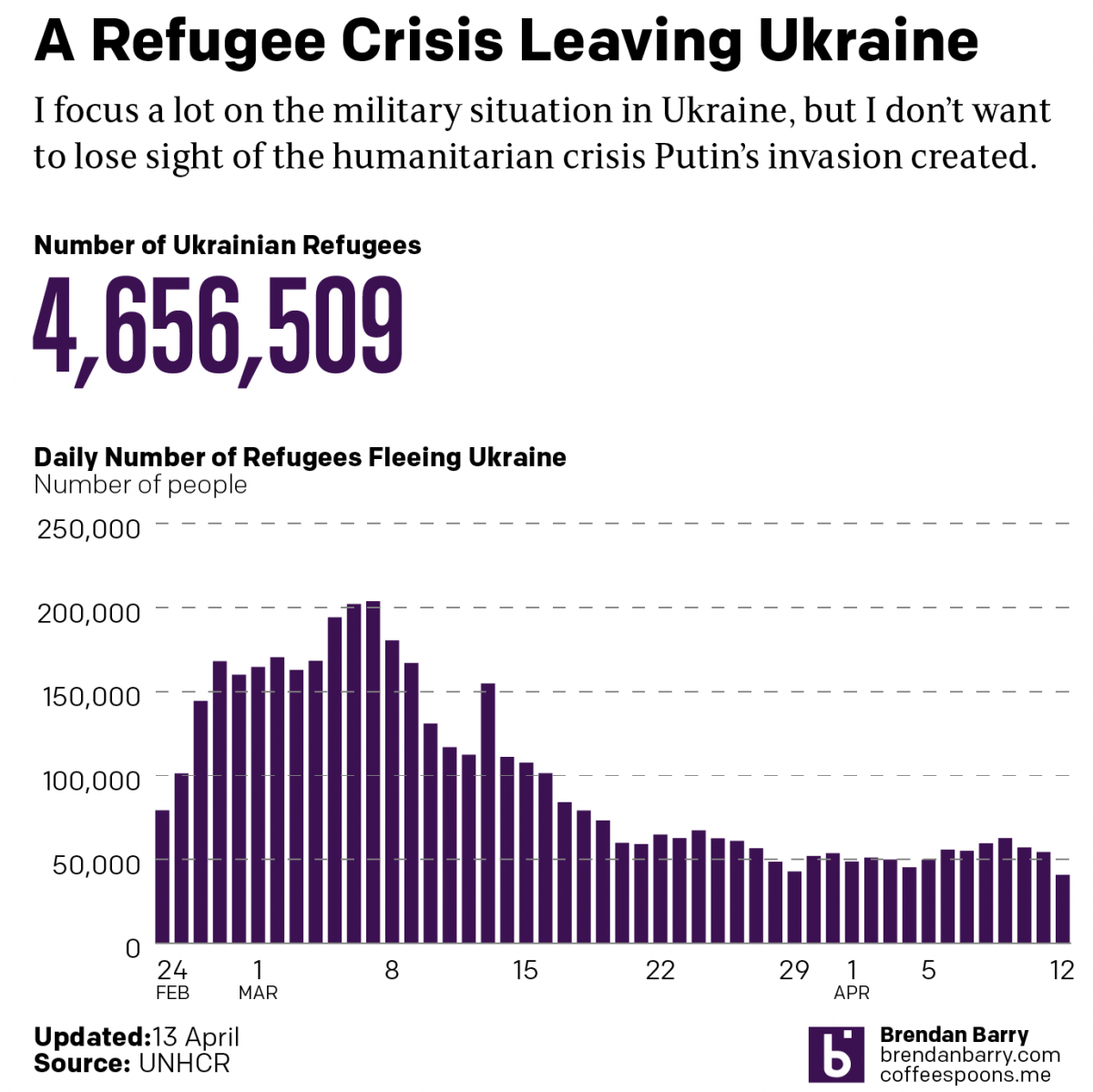

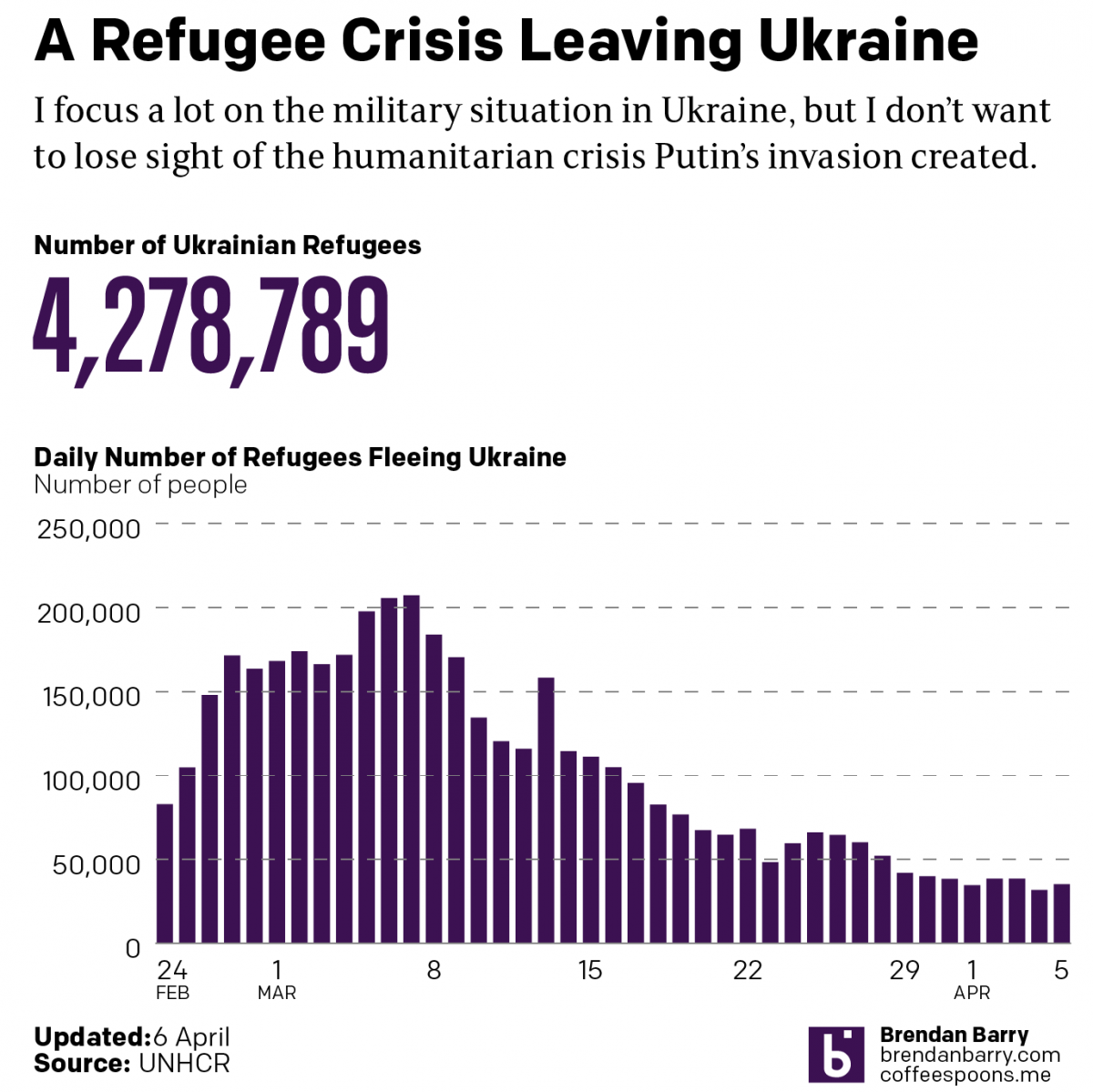

Russo-Ukrainian War Update: 6 April

Read on…: Russo-Ukrainian War Update: 6 April

Read on…: Russo-Ukrainian War Update: 6 AprilIt’s been a week since my last update and that’s in part because a lot has changed. When we last spoke, the Russians had announced they had successfully completed the first phase of the “special military operation”. They didn’t. Instead, Russian forces have completed a full-on retreat from northern Ukraine, sending troops and equipment back […]