Tag: infographic

-

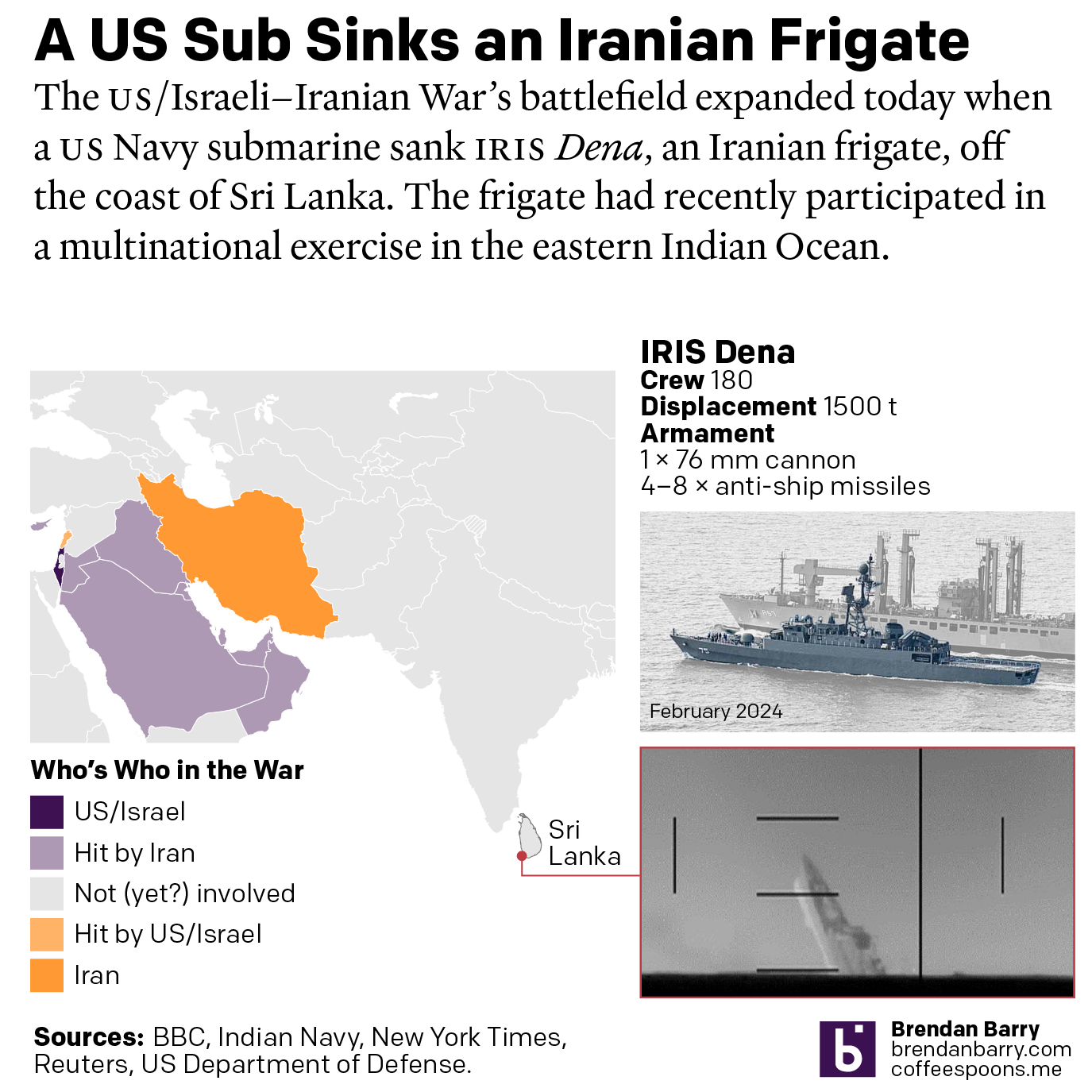

US Sub Sinks Ship off Sri Lanka

I woke up this morning thinking I was going to write about the graphics I mentioned on Monday. Instead, reading the news over breakfast brought me up to speed on the US Navy’s sinking of an Iranian frigate off the southwestern coast of Sri Lanka in the wee hours of the morning local time. Longtime…

-

Mission Accomplished

Last weekend the United States and Israel preemptively struck Iran and kicked off a regional war. As I type this Monday morning, the US–Israeli strike forced assassinated the ayatollah and numerous other senior Iranian officials—but this seems to have been anticipated to a degree and the regime quickly retaliated and has delegated roles and responsibilities.…

-

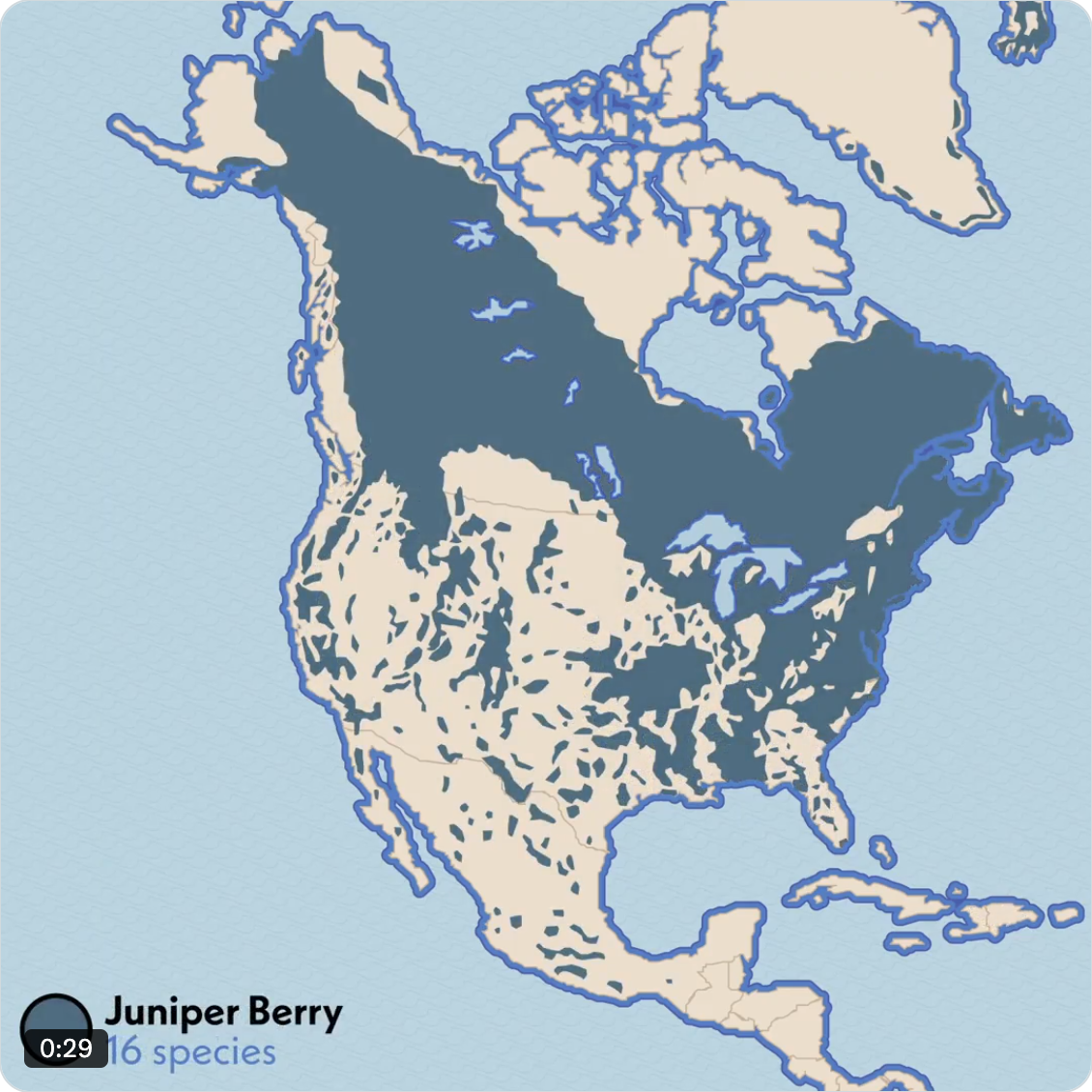

Jumpin’ Juniper

Happy Friday, all. Baseball is back with Spring Training now in full swing. That means checking in on my Twitter feeds for Red Sox baseball coverage. Sometimes that means seeing content not at all related to baseball. And given yesterday was the day before the weekend, this post stuck with me and now you can…

-

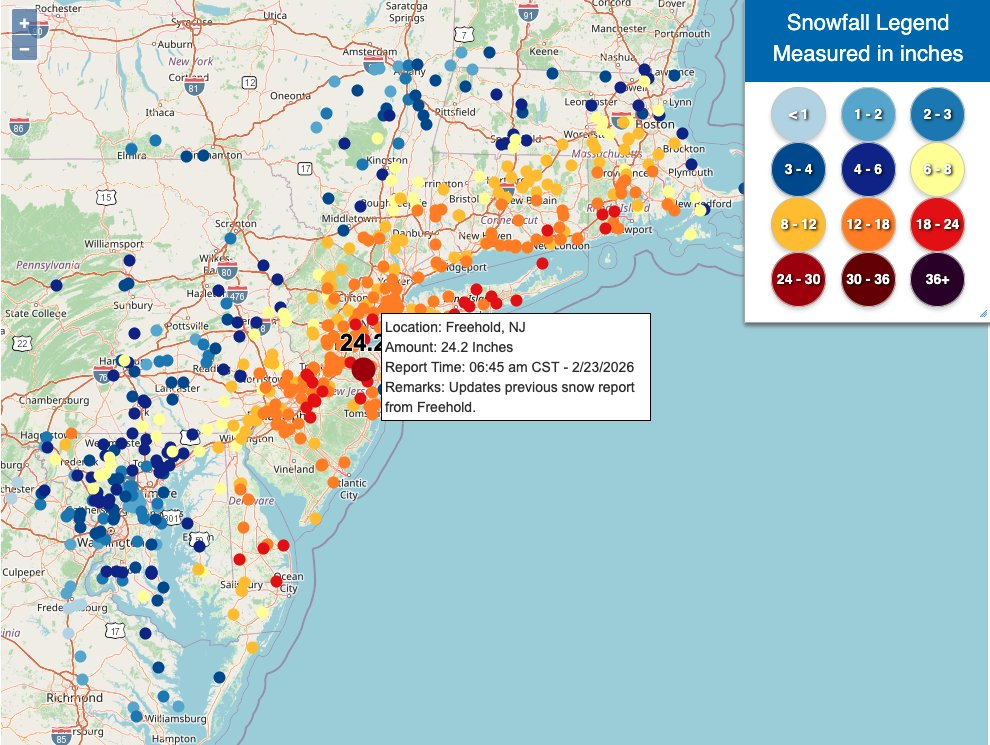

Winter Is Still Here

Ah, a blizzard. Even if the worst of the storm that recently impacted Philadelphia struck mostly at night, it still left a picturesque mess for the morning. I, however, was struck by some of the maps of the snowfall totals and I figured that would be worth sharing today. What got me started on this…

-

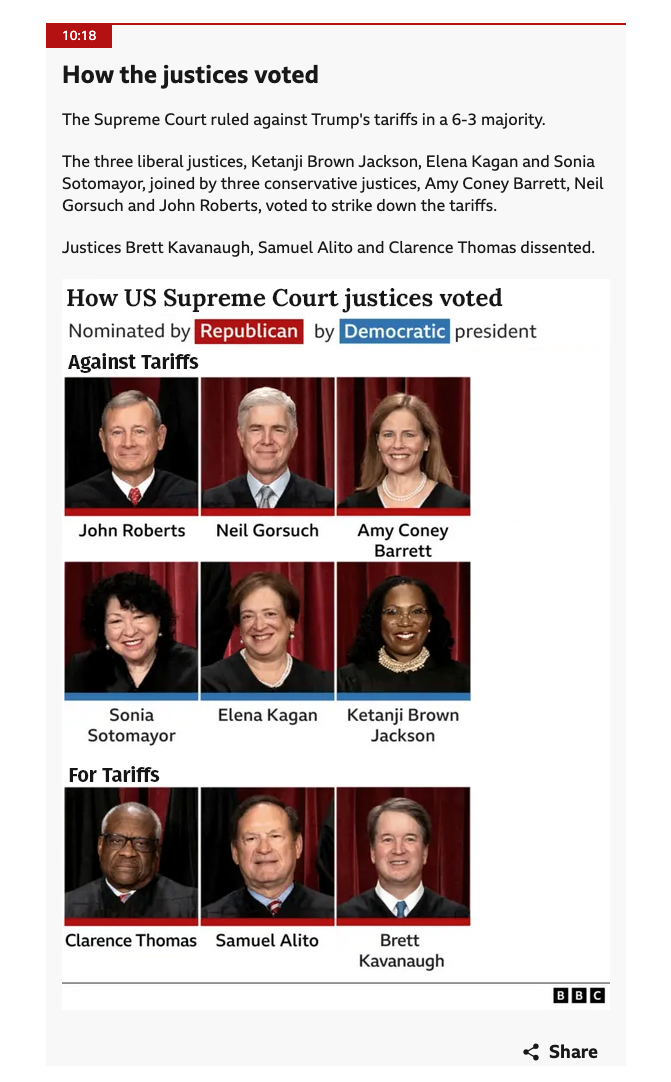

A Little Judgmental

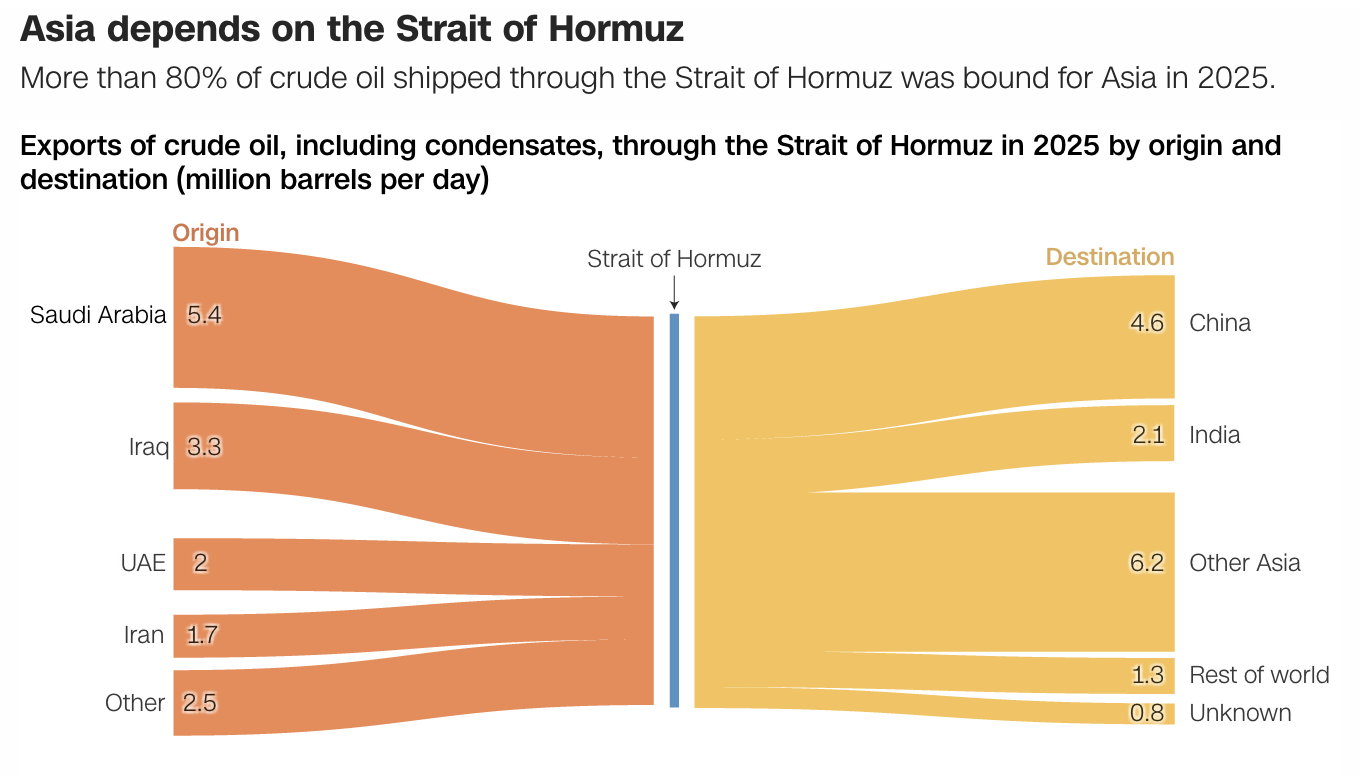

Editor’s note: I wrote this Friday afternoon, and then on Saturday afternoon a new BBC article included a graphic similar to my design. I address later on in this post. (I am also my own editor.) Friday’s US Supreme Court ruling struck down President Trump’s tariffs—mostly, not all—as unconstitutional. I had a browser tab up…

-

Not the Momma

Well, we made it to the weekend once again. Sometimes—often if I’m being honest—I will sit and watch birds hop around on my balcony, chirping to each other for a minute or two before they fly off to destinations unknown. And in the back of my mind I am always thinking, that little guy is…

-

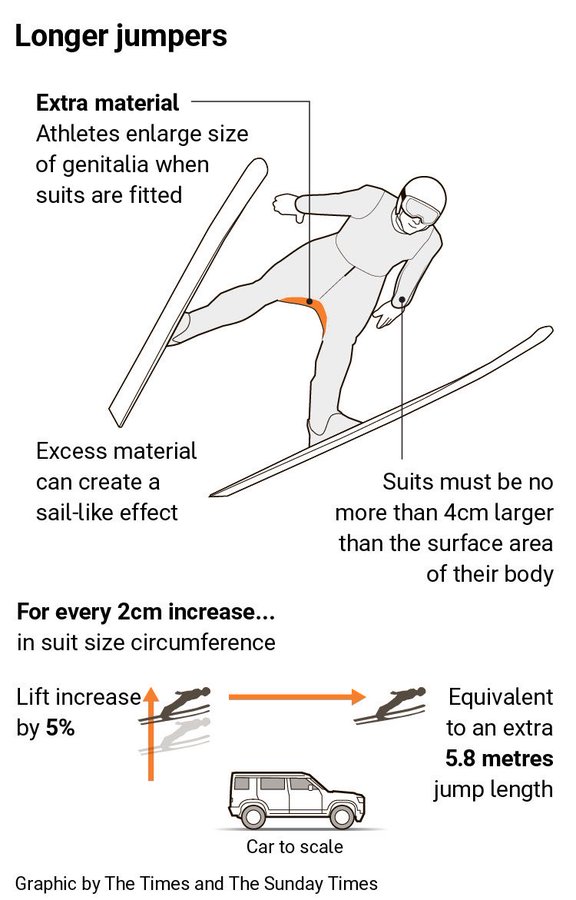

A Matter of Millimetres

Well we have made it to the weekend. And so it is the time to look at the area of men’s genitalia. This week on baseball Twitter the following graphic made the rounds. The graphic itself claims to be from the Times—the original, not the New York version for my American audience—though I have been…

-

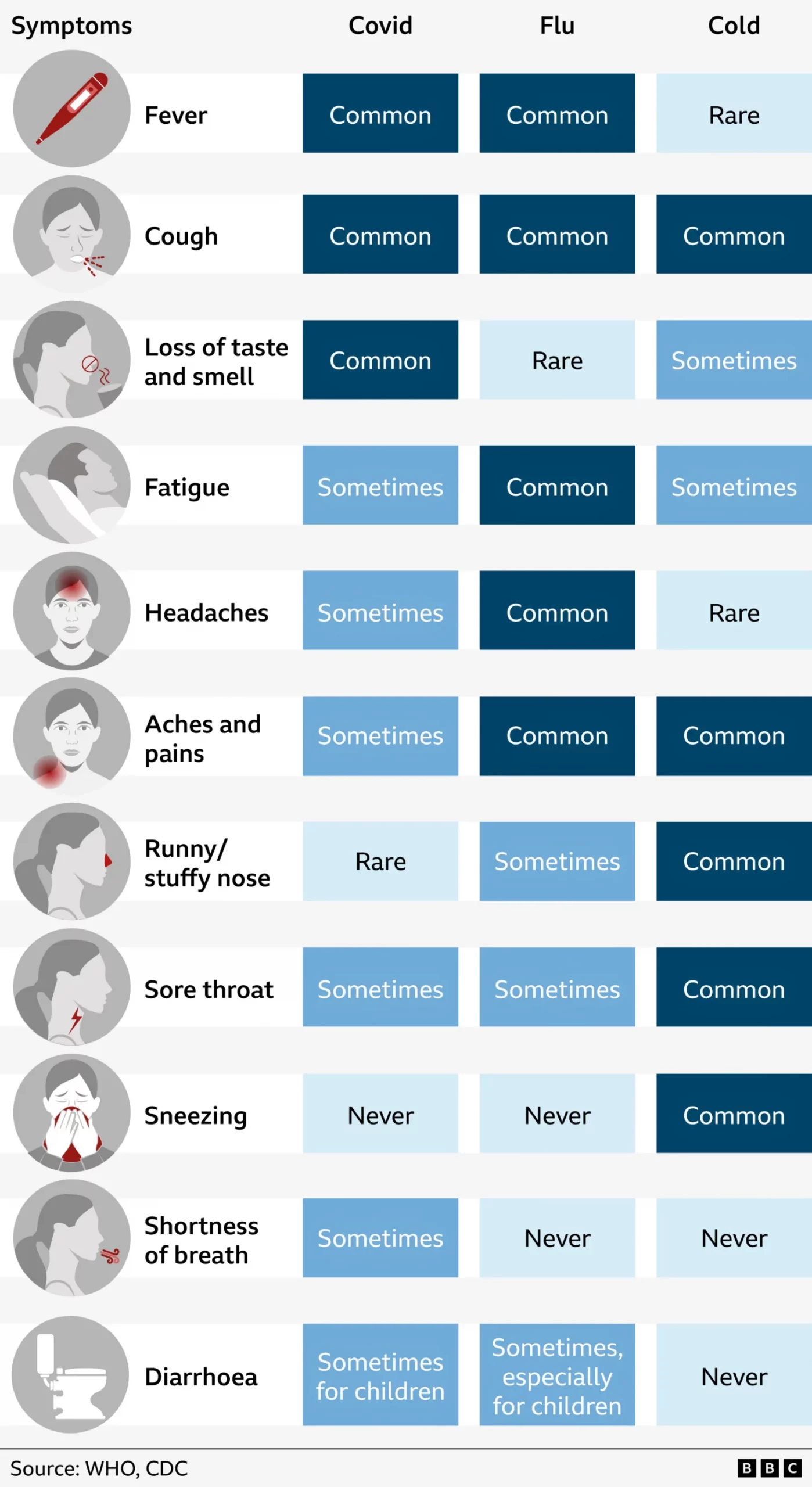

Aches, Fevers, and Chills, Oh My!

Last week I suffered from the aforetitled and wondered what just might be ailing me. My sore throat woke me up in the middle of the night with intense, sharp pain and reminded me of stories I had read earlier this flu season about “razor blade” sore throat associated with the latest COVID strain, Nimbus.…

-

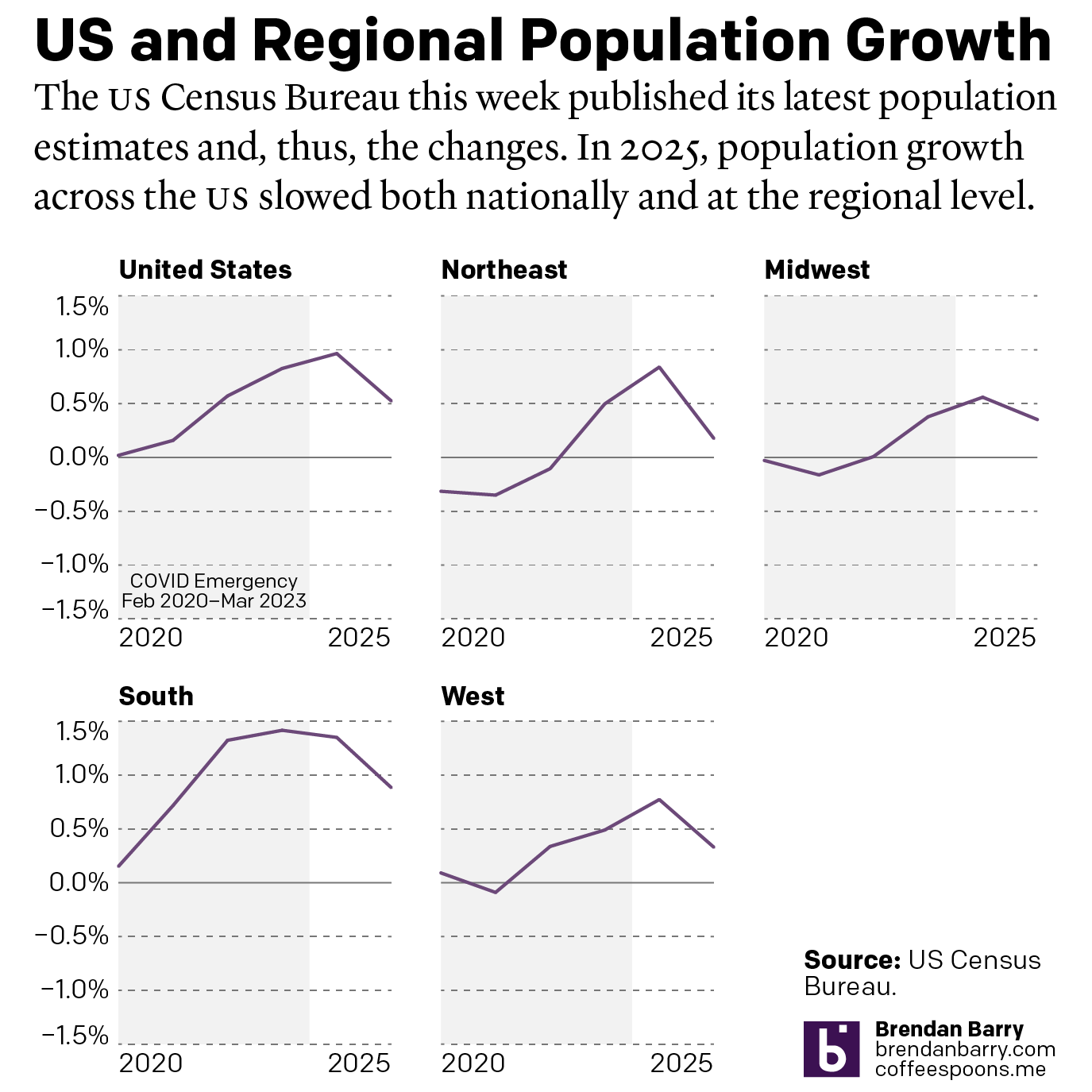

The Slowing of the Growth

This week the US Census Bureau released their population estimates for the most recent year and that includes the rate changes for the US, the Census Bureau defined regions, and the 50 states and Puerto Rico. I spent this morning digging into some of the data and whilst I will try to later to get…

-

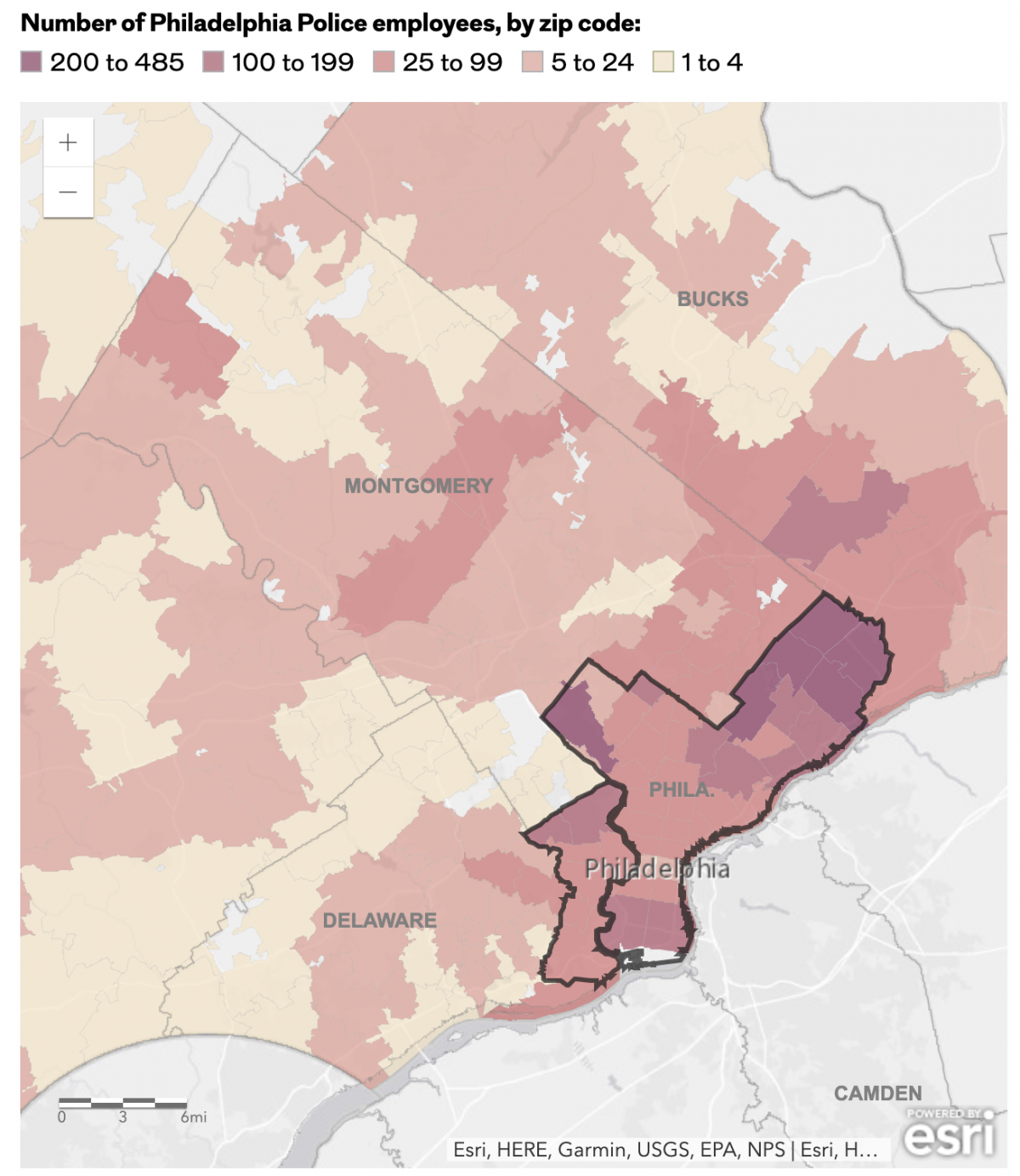

The Philadelphia Beat is Pretty Big

Early last week I read an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer about where the city’s police officers live, an important issue given the city’s loose requirement they reside within the city limits. Whilst most do, especially in the far Northeast, the Northwest, and South Philadelphia, a significant number live outside the city. (The city of…