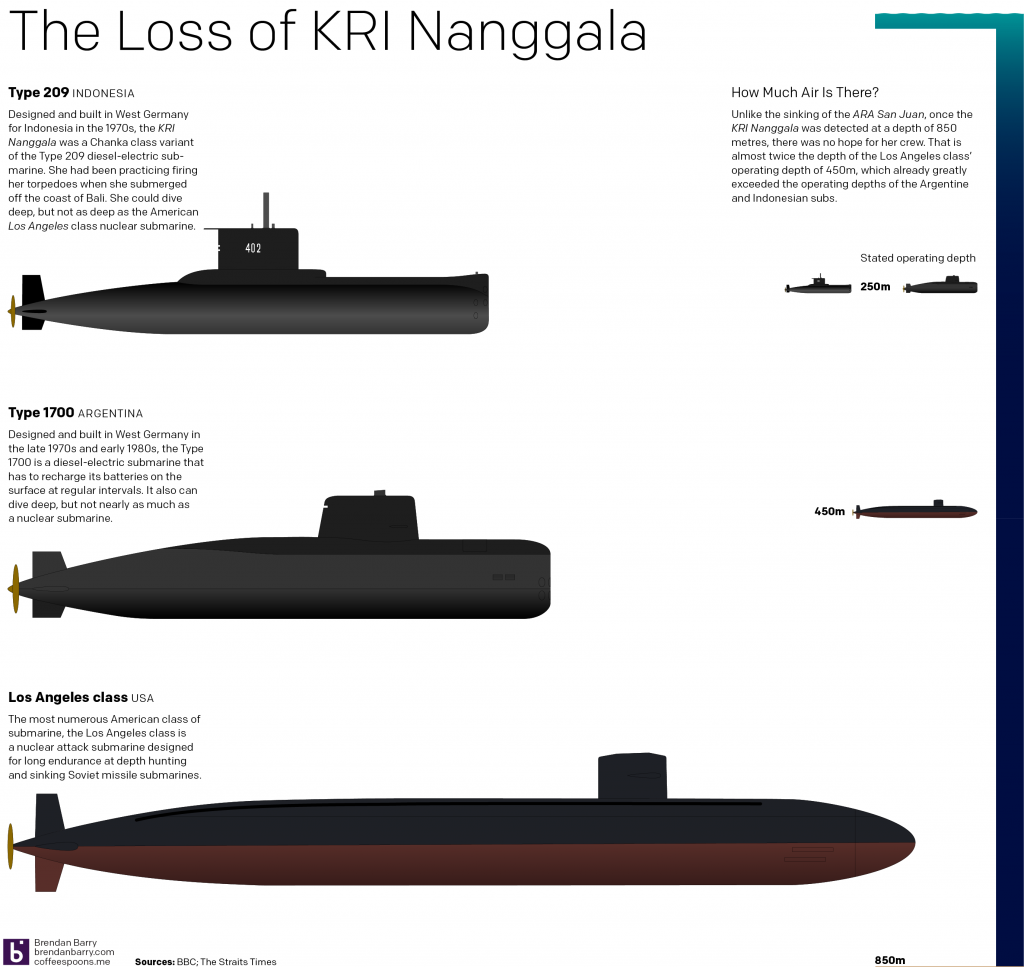

A few years ago, I created a piece about the missing Argentine submarine ARA San Juan. For those that do not remember, back in 2017, the Argentine Navy Type 1700 submarine ARA San Juan disappeared on a voyage from Ushuaia to Mar del Plata. At the time, people thought it may have sunk over the continental shelf where the seafloor was shallow enough the boat could have survived and not imploded. A year later, surveyors discovered the wreck at a much deeper depth east of the continental shelf. But at the time of the loss I made a graphic trying to show how the submarine was much smaller than the standard American submarine, the Los Angeles class, and how much deeper the Los Angeles class can dive.

So when the news broke this week that an Indonesian submarine, KRI Nanggala disappeared north of Bali, Indonesia, I decided to update the graphic. Since I finished the piece, however, the Indonesian Navy discovered the wreck in three pieces at 850 metres, far below even the presumed crush depth of the Los Angeles class. In other words, at that depth there was never any hope to find survivors.

The Indonesia submarine is an even smaller than the Argentine boat, both having an operating depth of about 250 metres—actual depths are generally not disclosed because, well, military secrets. But the graphic shows just how far below that depth the sub’s wreckage rests.

Credit for the piece is mine.