Yesterday we looked at a piece by the Boston Globe that mapped out all of David Ortiz’s home runs. We did that because he has just been voted into baseball’s Hall of Fame. But to be voted in means there must be votes and a few weeks after the deadline, the Globe posted an article about how that publication’s eligible voters, well, voted.

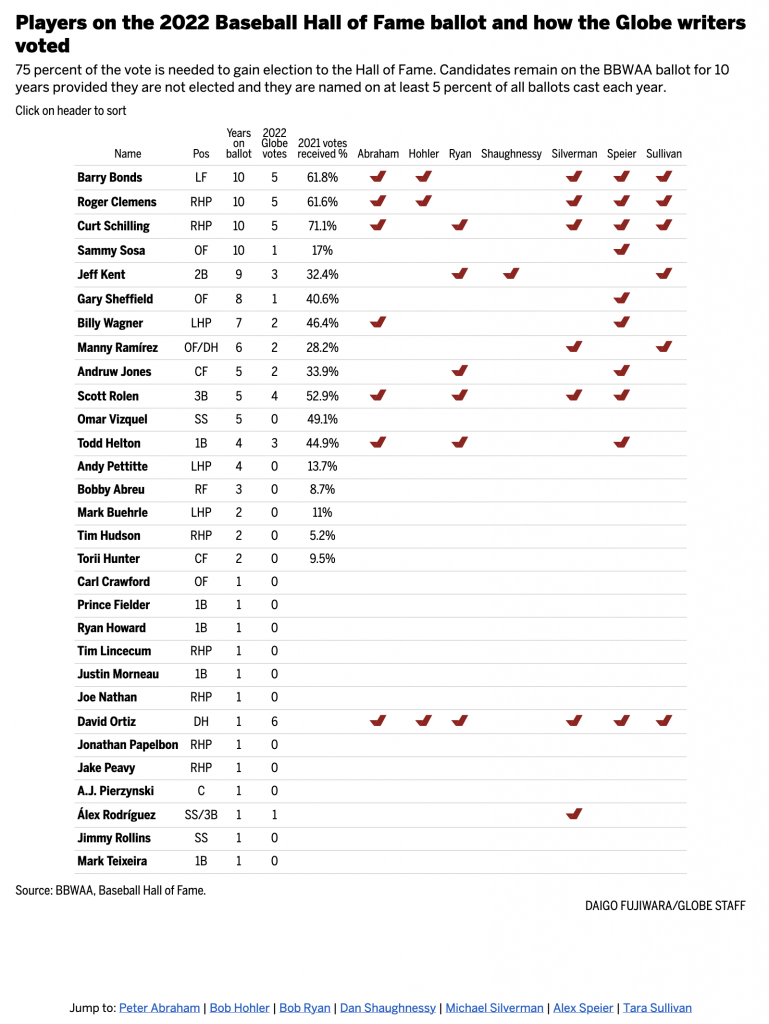

The graphic here was a simple table. But as I’ll always say, tables aren’t an inherently bad or easy-way-out form of data visualisation. They are great at organising information in such a way that you can quickly find or reference specific data points. For example, let’s say you wanted to find out whether or not a specific writer voted for a specific ballplayer.

Simple red check marks represent those players for whom the Globe’s eligible staff voted. I really like some of the columns on the left that provide context on the vote. For the unfamiliar, players can only remain on the list for up to ten years. And so for the first four, this was their last year of eligibility. None made the cut. Then there’s a column for the total number of votes made by the Globe’s staff. Following that is more context, the share of votes received in 2021. Here the magic number if 75% to be elected. Conversely, if you do not make 5% you drop off the following year. Almost all of those on their first year ballot failed to reach that threshold.

The only potential drawback to this table is that by the time you reach the end of the table, there are few check marks to create implicit rules or lines that guide you from writer to player. David Ortiz’s placement helps because six—remarkably not all Globe writers voted for him—it grounds you for the only person below him (alphabetically) to receive a vote. And we need that because otherwise quickly linking Alex Rodriguez to Alex Speier would be difficult.

Finally below the table we have jump links to each writer’s writings about their selections. And if you’ll allow a brief screenshot of that…

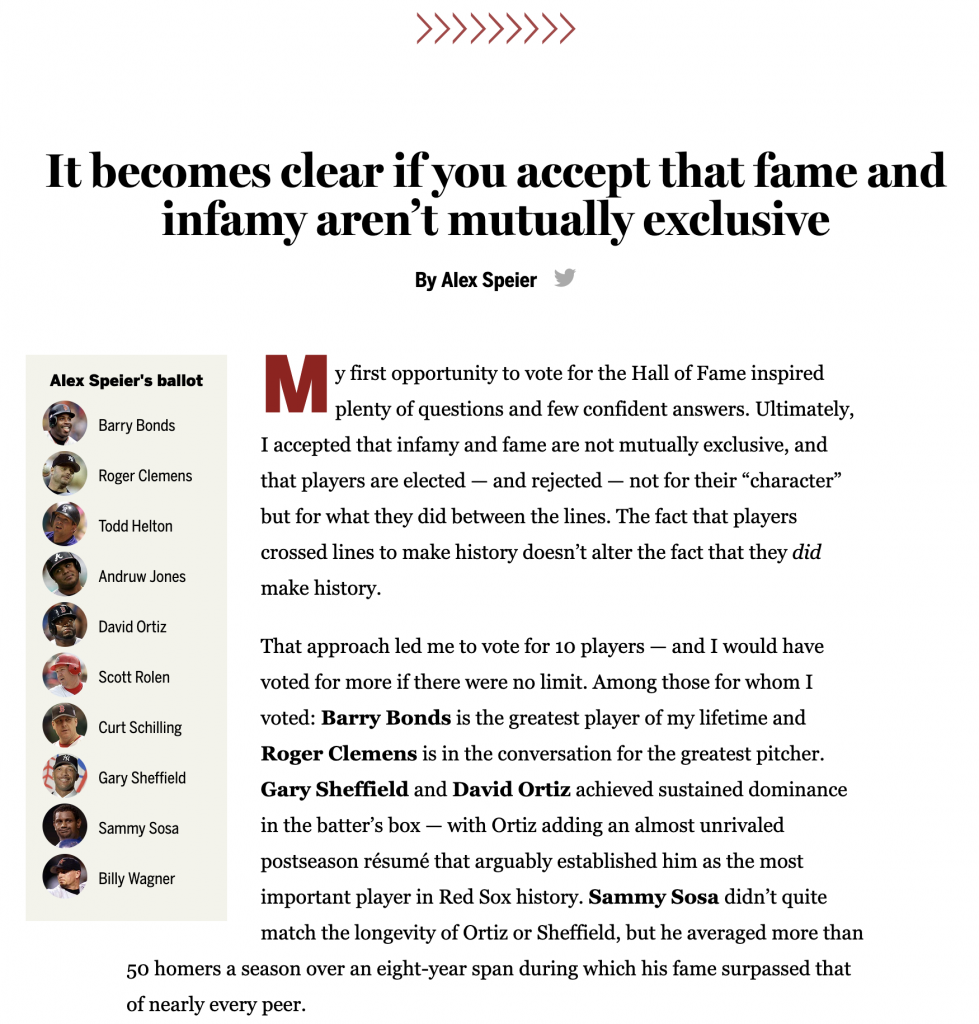

We have a nicely designed section here. Designers delineated each author’s section with red arrows that evoke the red stitching on a baseball. It’s a nice design tough. Then each author receives a headline and a small call out box inside which are the players—and their headshots—for whom the author voted. An initial dropped capital (drop cap), here a big red M, grabs the reader’s attention and draws them into the author’s own words.

Overall this was a solidly designed piece. I really enjoyed it. And for those who don’t follow the sport, the table is also an indicator of how divisive the voting can be. Even the Globe’s writers couldn’t unanimously agree on voting for David Ortiz.

Credit for the piece goes to Daigo Fujiwara and Ryan Huddle.