After working pretty much non-stop all spring and summer, your humble author finally took a few days off and throw in a bank holiday and you are looking at a five-day weekend. But, because this is 2020 travelling was out of the question and so instead I hunkered down to finish writing/designing an article I have been working on for the last several weeks/few months.

The main write-up—it is a lengthy-ish read so you may want to brew a cup of tea—is over at my data projects site. This is the first project I have really written about for that since spring/summer 2016. Some of my longer-listening readers may recall that the penultimate piece there I wrote about Pennsyltucky was inspired by work I did here at Coffeespoons.

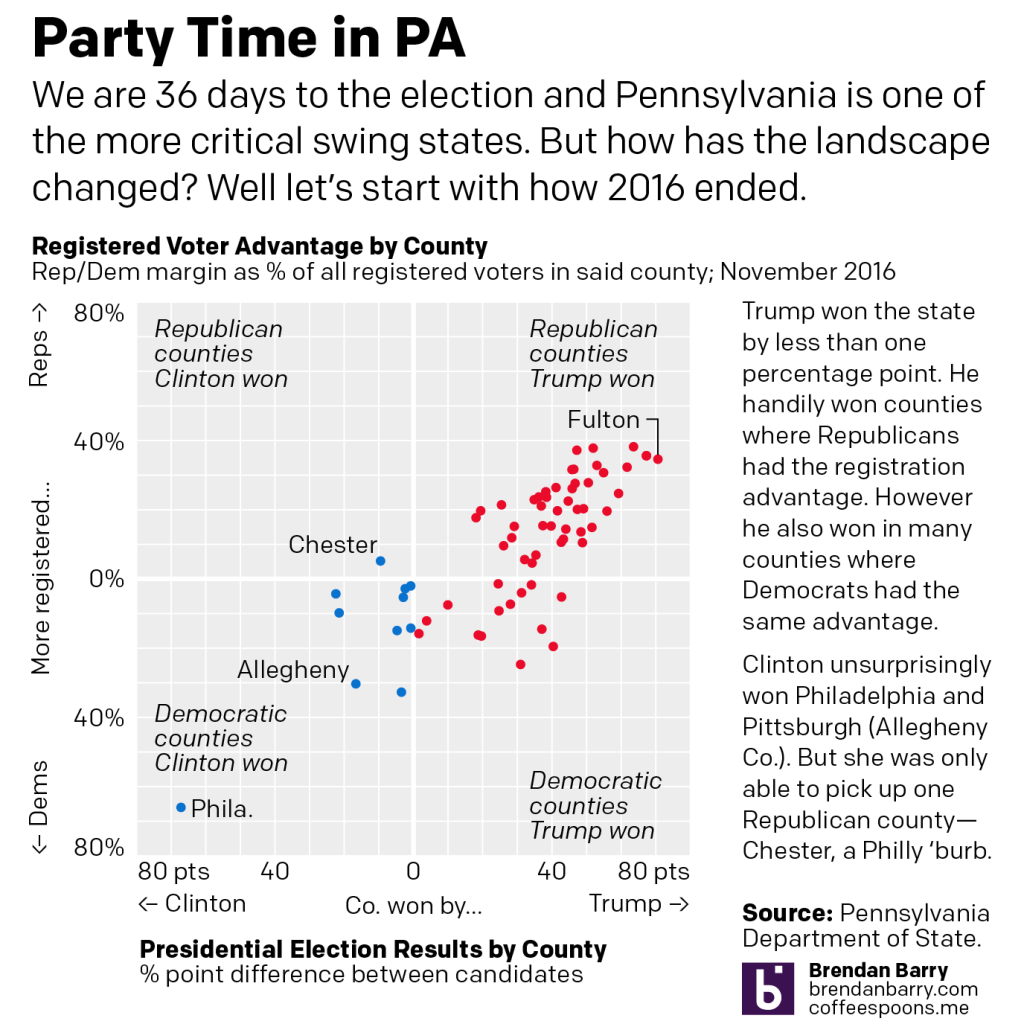

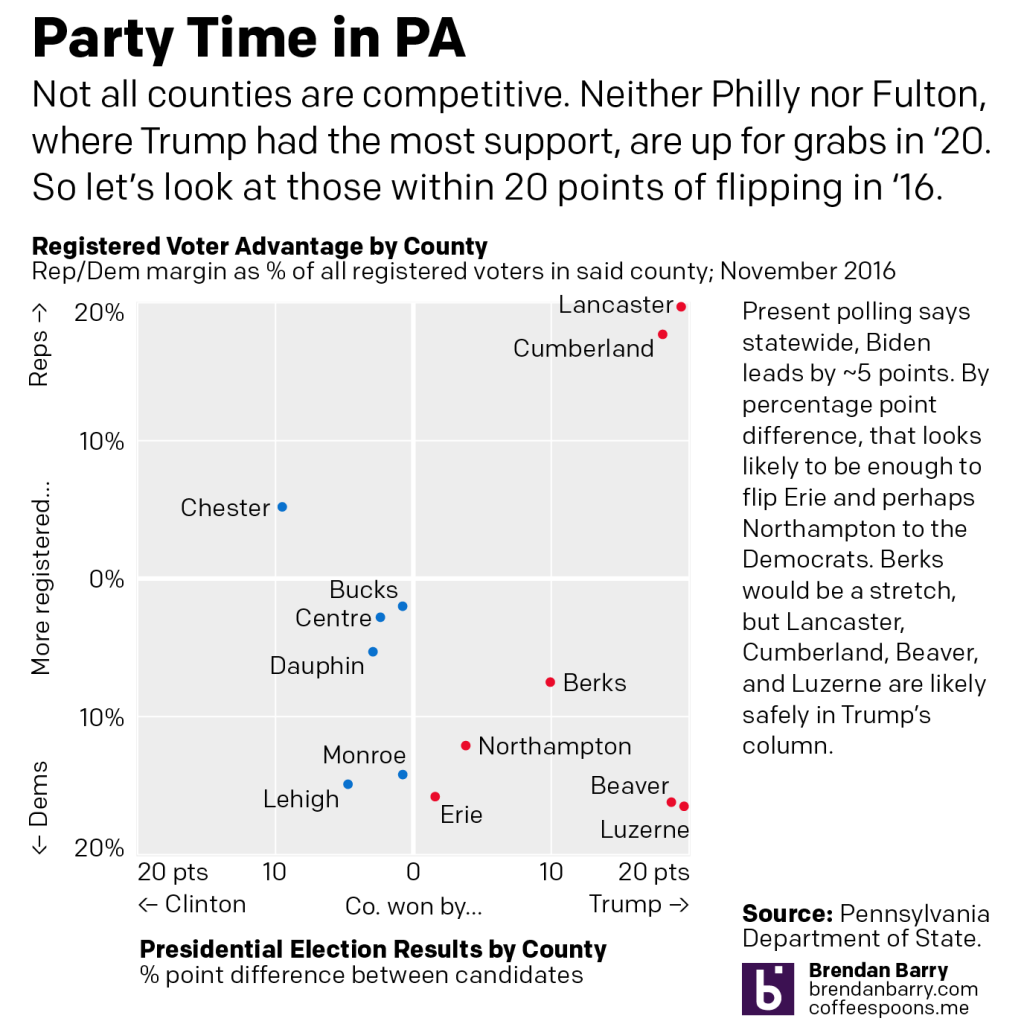

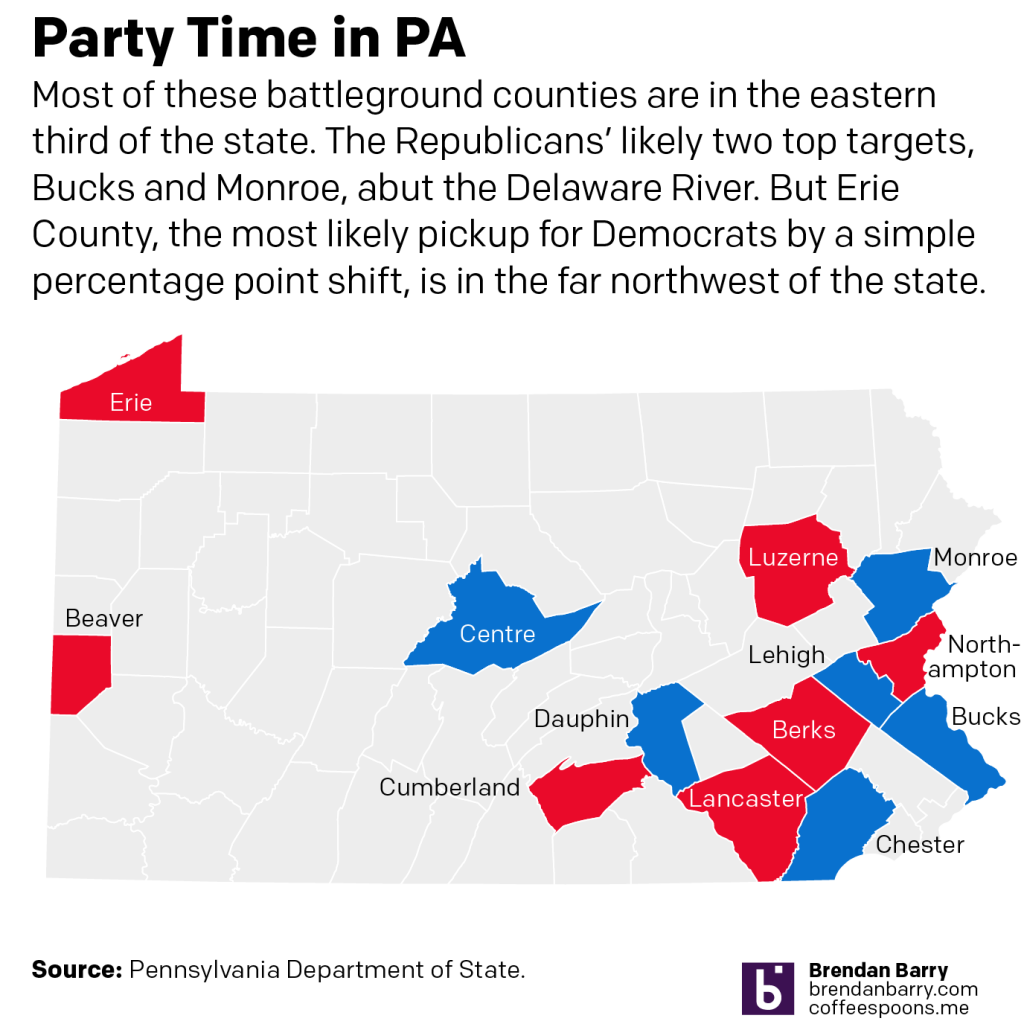

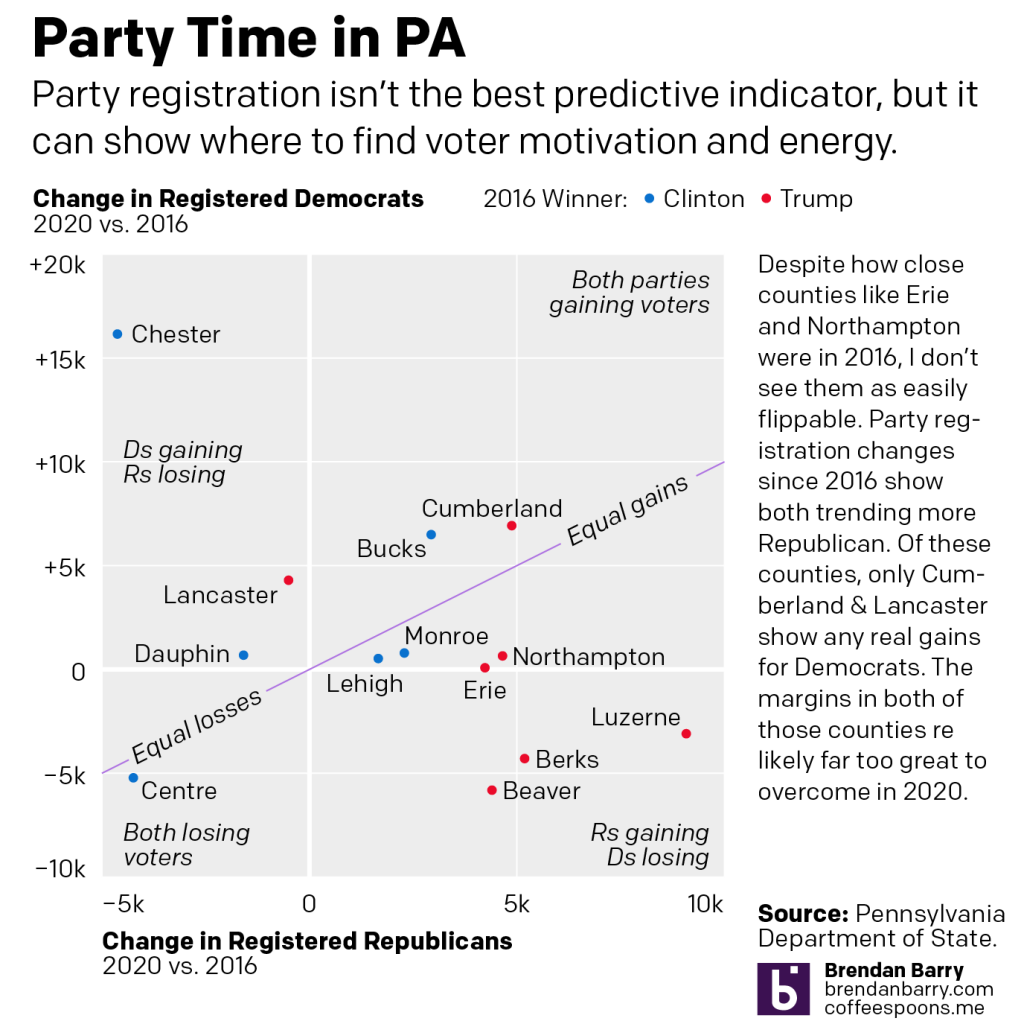

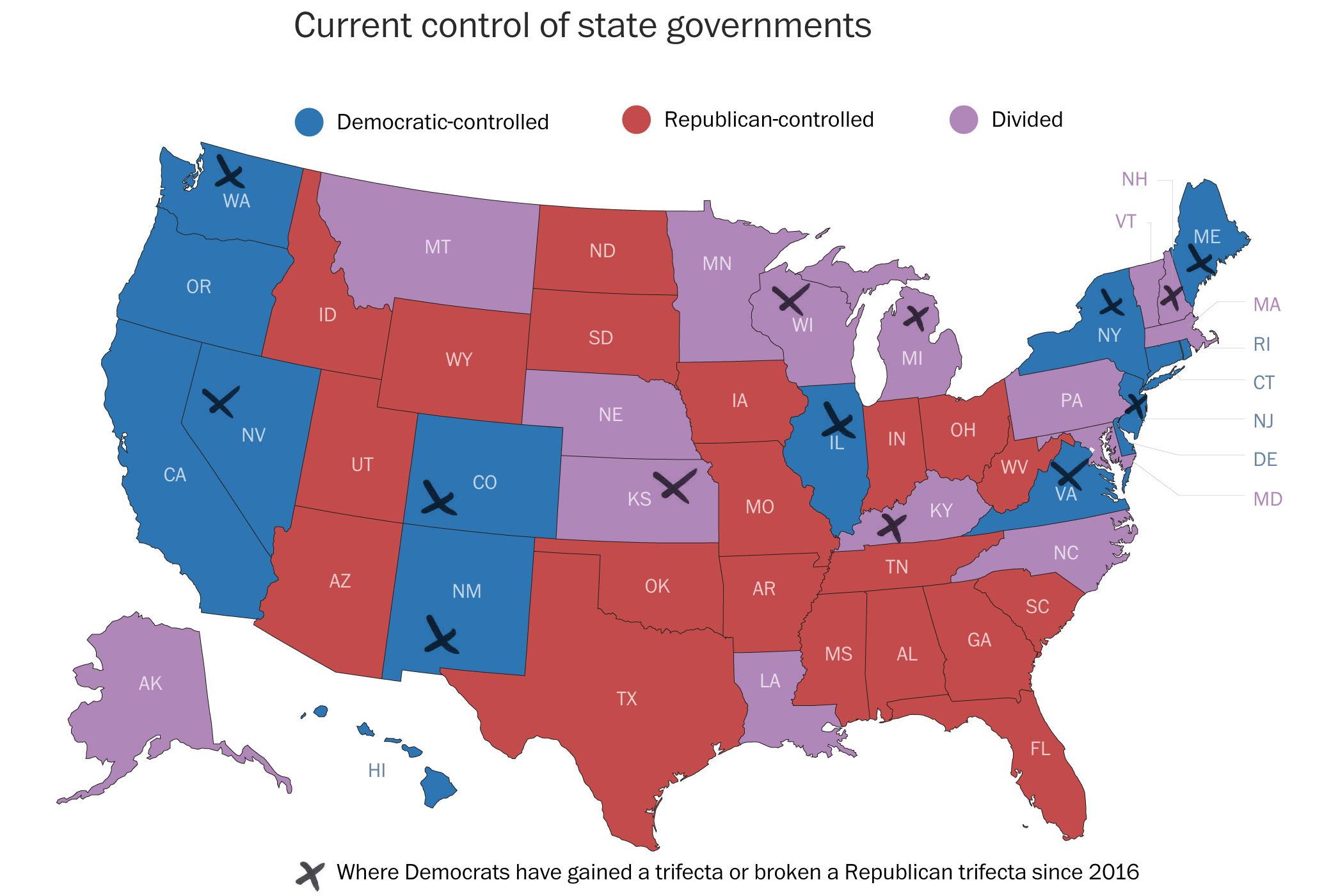

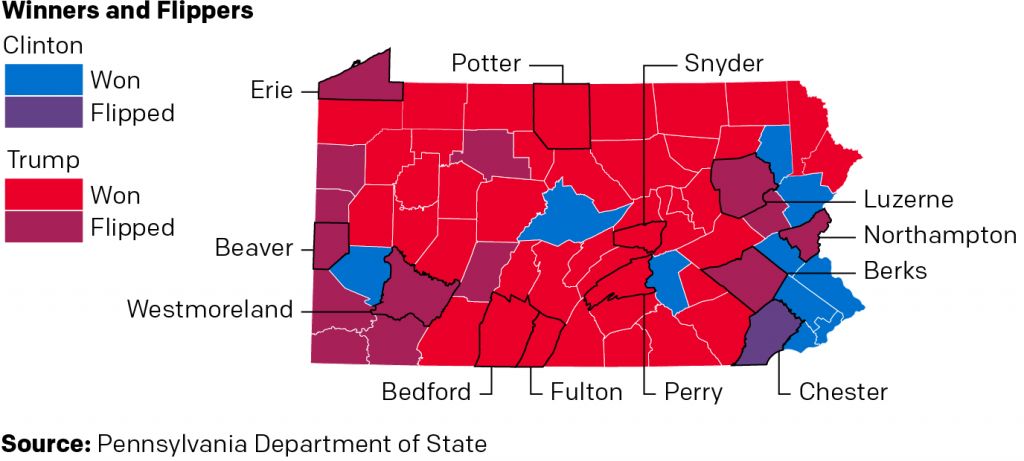

To an extent, so is this piece. I wrote about Trumpsylvania, the political realignment of the state of Pennsylvania. 2016 and the state’s vote for Donald Trump was less an aberration than many think. It was the near-end result of a decades-long transformation of the state’s political geography. And so I looked at the data underlying the shift and how and where it occurred.

And originally, I had a slightly different conclusion as to how this related to Pennsylvania in the upcoming 2020 election. But, the whole 2020 thing made me shift my thinking slightly. But you’ll have to read the whole thing to understand what I’m talking about. I will leave you with one of the graphics I made for the piece. It looks at who won each county in the state, but also whether or not the candidate was able to flip the county. In other words, was Clinton able to flip a Republican county? Was Trump able to flip a Democratic county?

Let me know what you think.

And of course, many, many thanks to all the people who suffered my ideas, thoughts, and early drafts over the last several weeks. And even more thanks to those who edited it. Any and all mistakes or errors in the piece are all mine and not theirs.

Credit for the piece is mine.