In several decades…

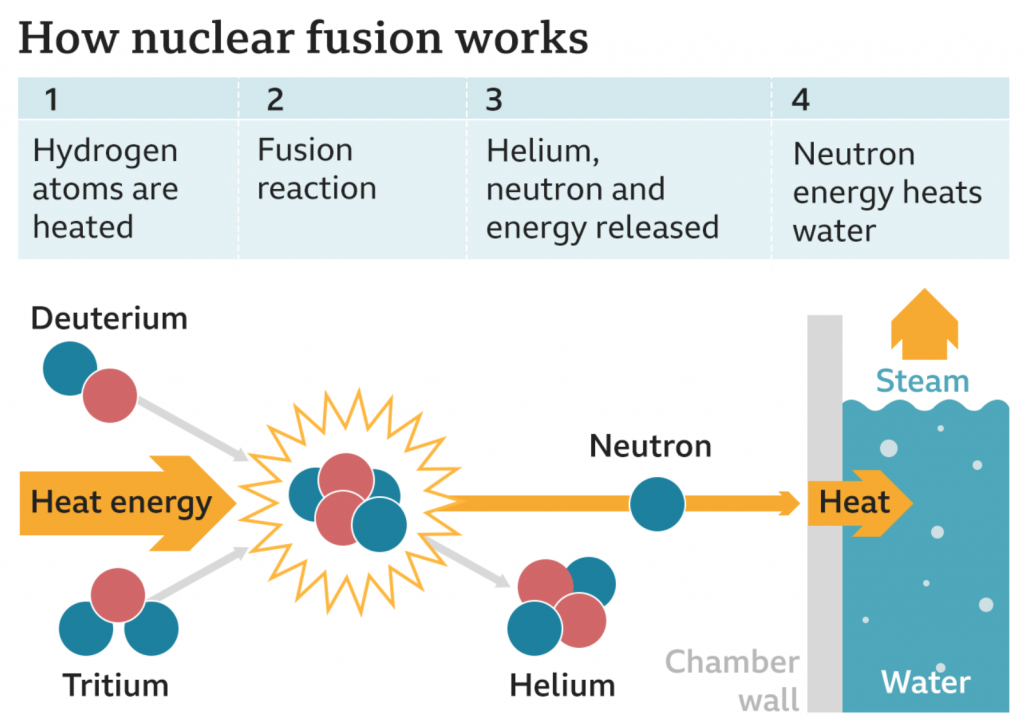

Just a quick little piece today, a neat illustration from the BBC that shows how the process of nuclear fusion works. The graphic supports an article detailing a significant breakthrough in the development of nuclear fusion. Long story short, a smaller sort-of prototype successfully proved the design underpinning a much larger fusion reactor currently under construction in France. We are potentially on our way to proving the viability of nuclear fusion as an energy source.

Why is that important? Well, first of all, no carbon emissions. Nuclear fusion powers the Sun, where hydrogen is fused with hydrogen to produce helium and in the process release an enormous amount of energy. Mankind wants to take that energy and use it to heat water to generate steam to spin turbines to create electricity.

And we use a lot of electricity.

So how does fusion work?

The BBC graphic shows how. This is a bit simplified, even for my tastes, but it’s generally pretty good. For example, I probably would have labelled protons and neutrons earlier (to the left) of the graphic. And my big question mark is about the widths of the arrows, because if the width of the arrows relates to the scale of the energy, as that is the crux of the matter. (See what I did there?)

Basically when we want to generate energy we want to add as little as possible to start a reaction to net as much output as possible. A little bit of energy is used to split a uranium isotope and that generates a tremendous amount of energy. Thus far with nuclear fusion, however, we use a lot of energy to fuse hydrogen into helium and get little back as output. In other words, a net loss.

The graphic omits how this reactor in the UK works, by using a doughnut-shaped vessel to contain the hydrogen reaction. To do this they use superconducting magnets to generate powerful electromagnetic fields. This contains the hydrogen that turns into a superheated plasma. After all, it’s not like there are any materials known to man that can safely contain the temperatures of the Sun. But we have evidence that as the amount of plasma scale up, the closer we get to breaking even. And that’s the goal for the French reactor.

The other big question in the room is how this helps us with climate change, because as I stated up top, no carbon emissions. Unfortunately, not much. The French reactor is still several years away from being complete. And if that works as expected, commercial-scale reactors powering electricity generation stations are many more years away. Fusion will help power us into the 22nd century. And so we will still need nuclear fission and renewables to get us through the 21st.

Credit for the piece goes to the BBC graphics department.