Tag: bar chart

-

Just a Thought About a Thing That’s Been Nipping at Me

The democratisation of design tools ostensibly allows people to create high-quality graphics. But I think we can all admit to ourselves we see a lot of work that…misses its mark. As a general rule, I do not often post work here by untrained designers. My peers and I have the benefit of education and experience…

-

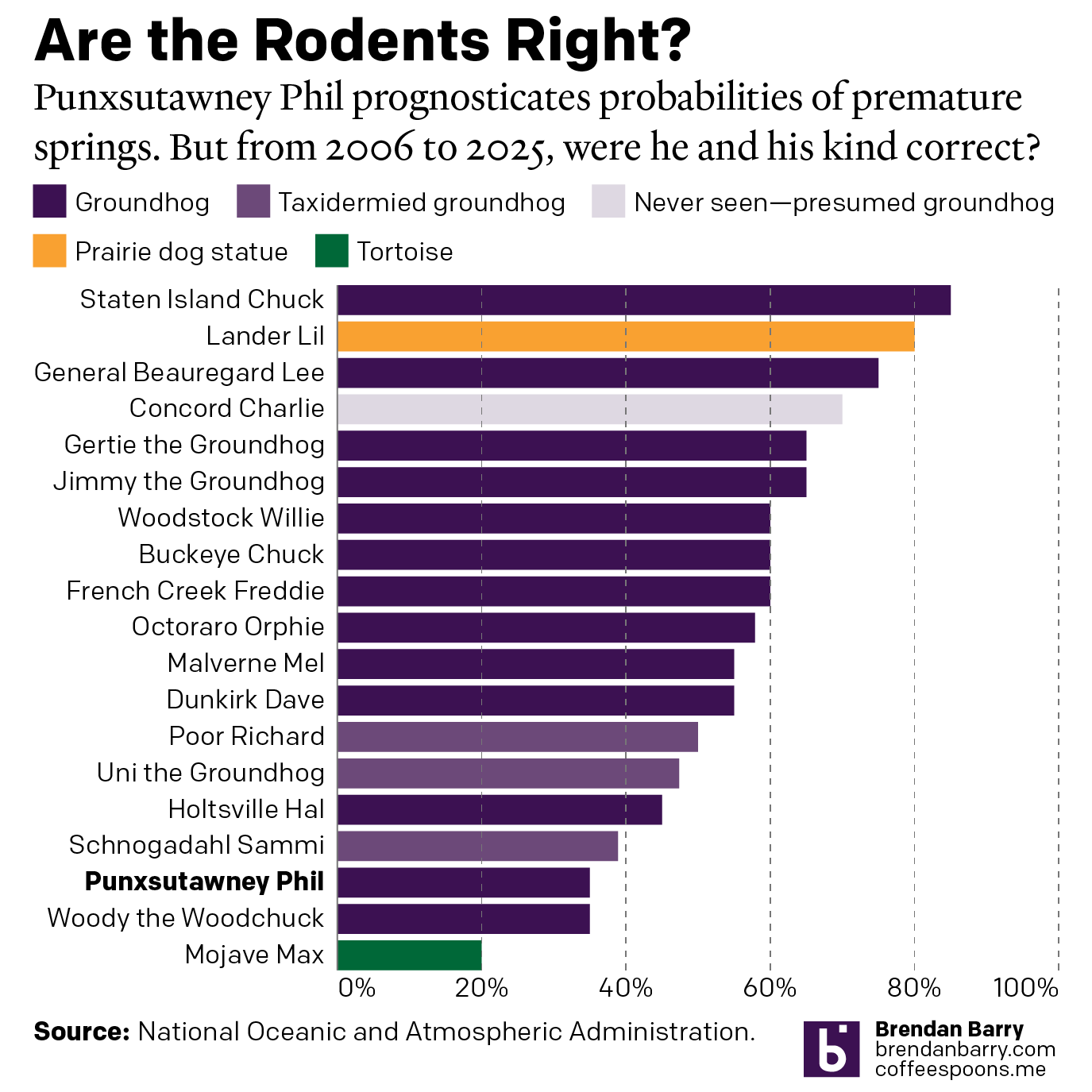

Do We Do This Every Year?

Every year on Groundhog’s Day I feel as if more and more critters crawl up from the Earth to offer their portents of prolonged winter. And every year we look backwards with the fullness of meteorological observations to evaluate the accuracy of these armchair—armburrow?—forecasters. This year, the Philadelphia Inquirer’s required article on the matter included…

-

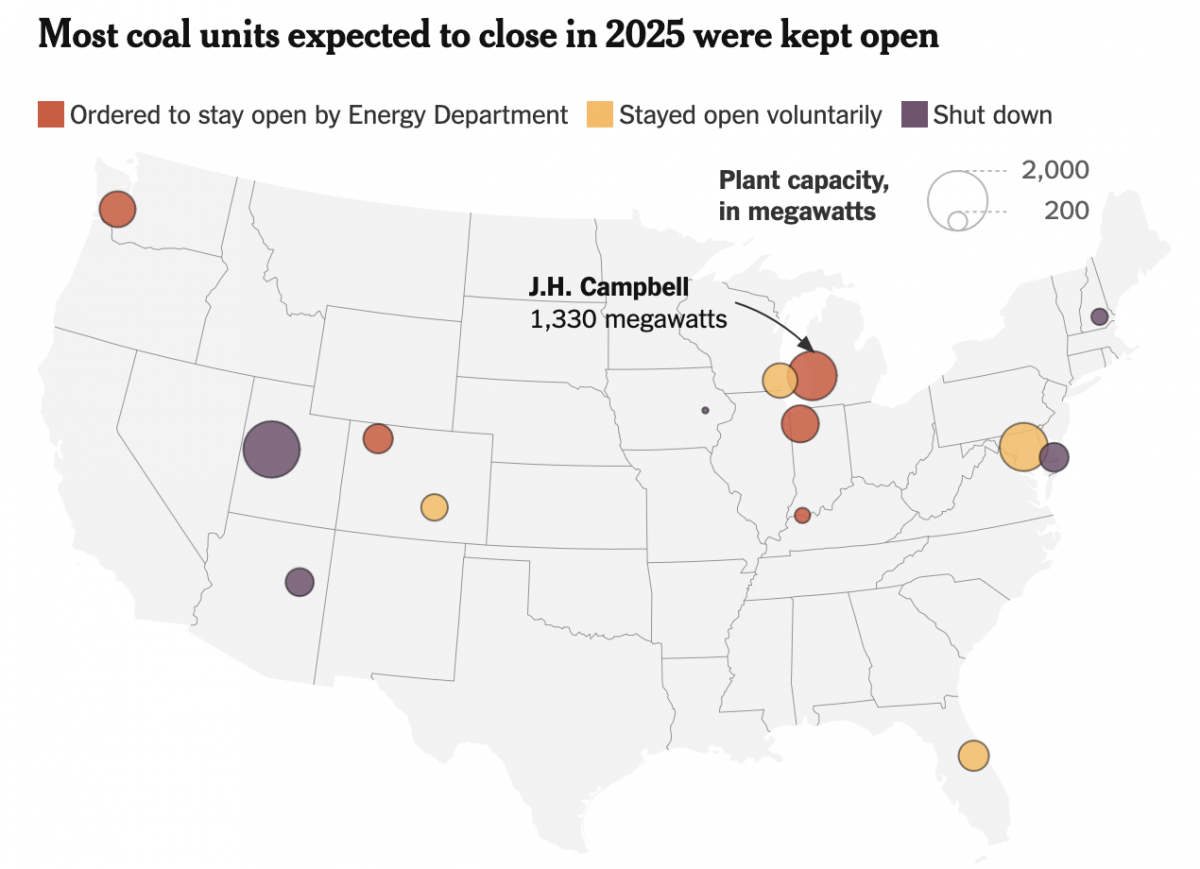

The Phoenix Rises from the Charcoal

To be clear, climate change is real. We know humanity drives the bulk of it via emissions of carbon and other greenhouse gasses, e.g. methane. Electricity generation plays a significant role in the total output, though not all means of generating power are equal. Wind, solar, hydro, and nuclear, for example, produce no carbon emissions.…

-

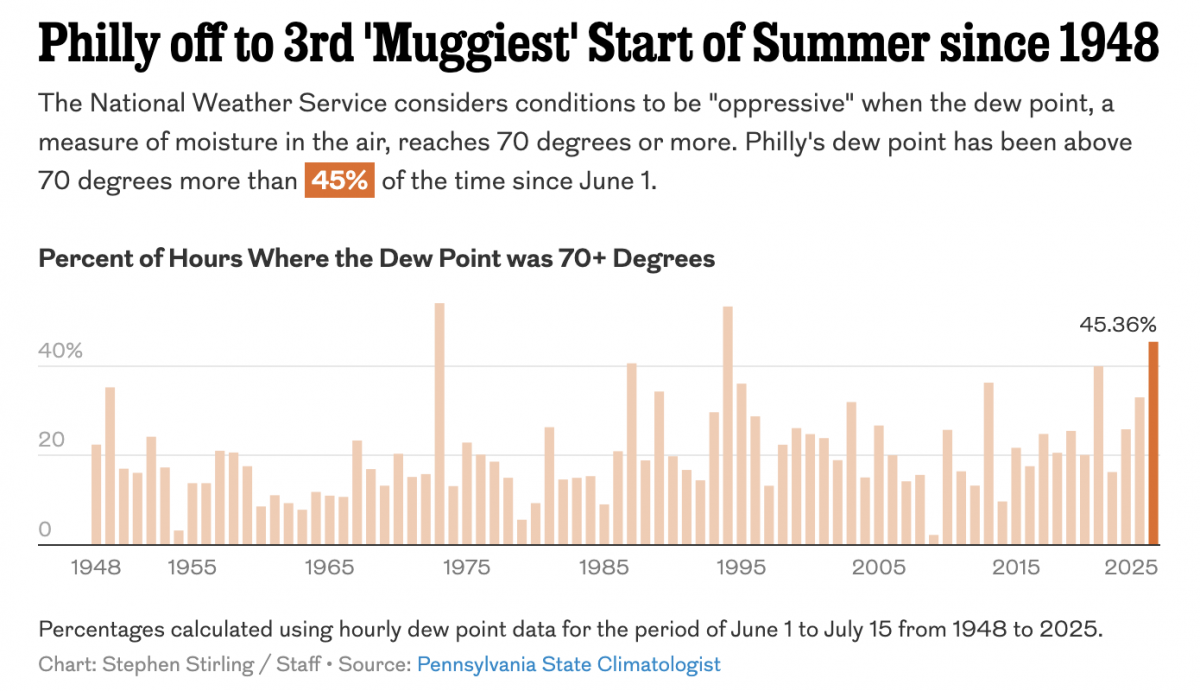

Just a Little Axis if You Please

In my last post, I commented upon a graphic from the Philadelphia Inquirer where a min/max axis line would have been helpful. This post is a quick follow-up of sorts, because a week ago I flagged something similar for me to perhaps mention on Coffee Spoons. So here I shall mention away. We have another…

-

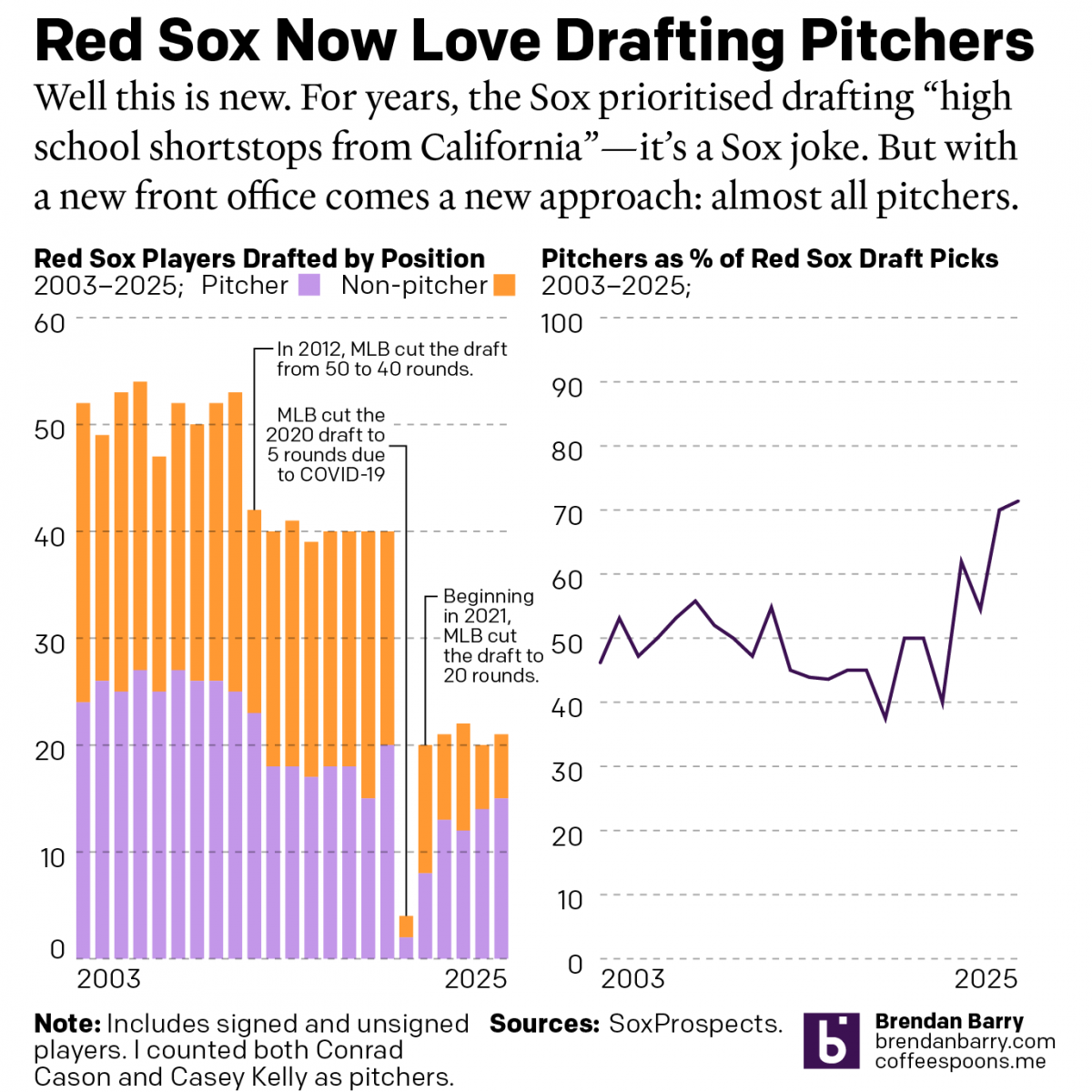

2025 Red Sox Draft Breakdown

Monday and Tuesday, Major League Baseball conducted its amateur player draft, wherein teams select American university and high school players. They have two weeks to sign them and assign them. (Though many will not actually play this year.) Two years ago the Red Sox installed Craig Breslow as their new chief baseball organisation. He has…

-

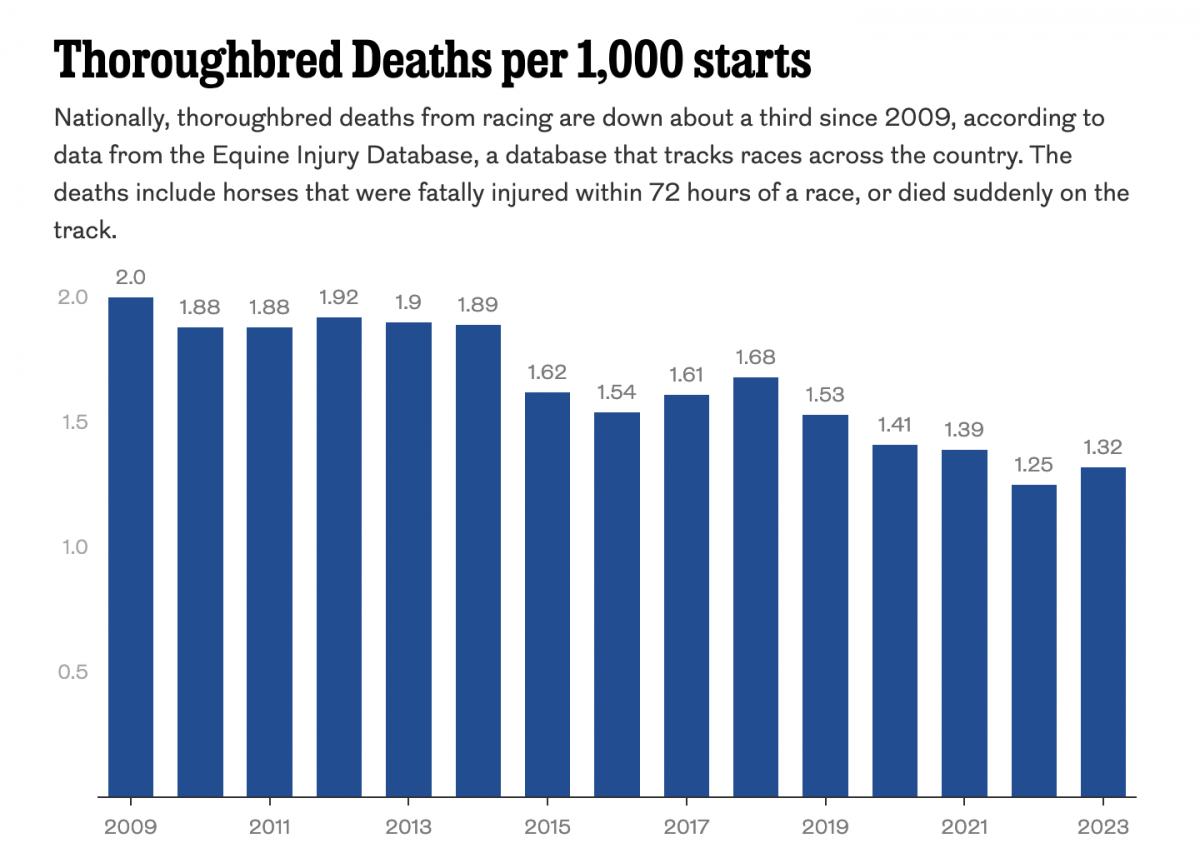

Racing to the Final Finish Line

Thoroughbred racing is big business. And Philadelphia’s Parx Casino owns a racing track that, in a recent article in the Philadelphia Inquirer, has seen a number of horse deaths. The article includes a single graphic worth noting, a bar chart showing the thoroughbred death rate. The graphic contrasts rising deaths at Parx with a national…

-

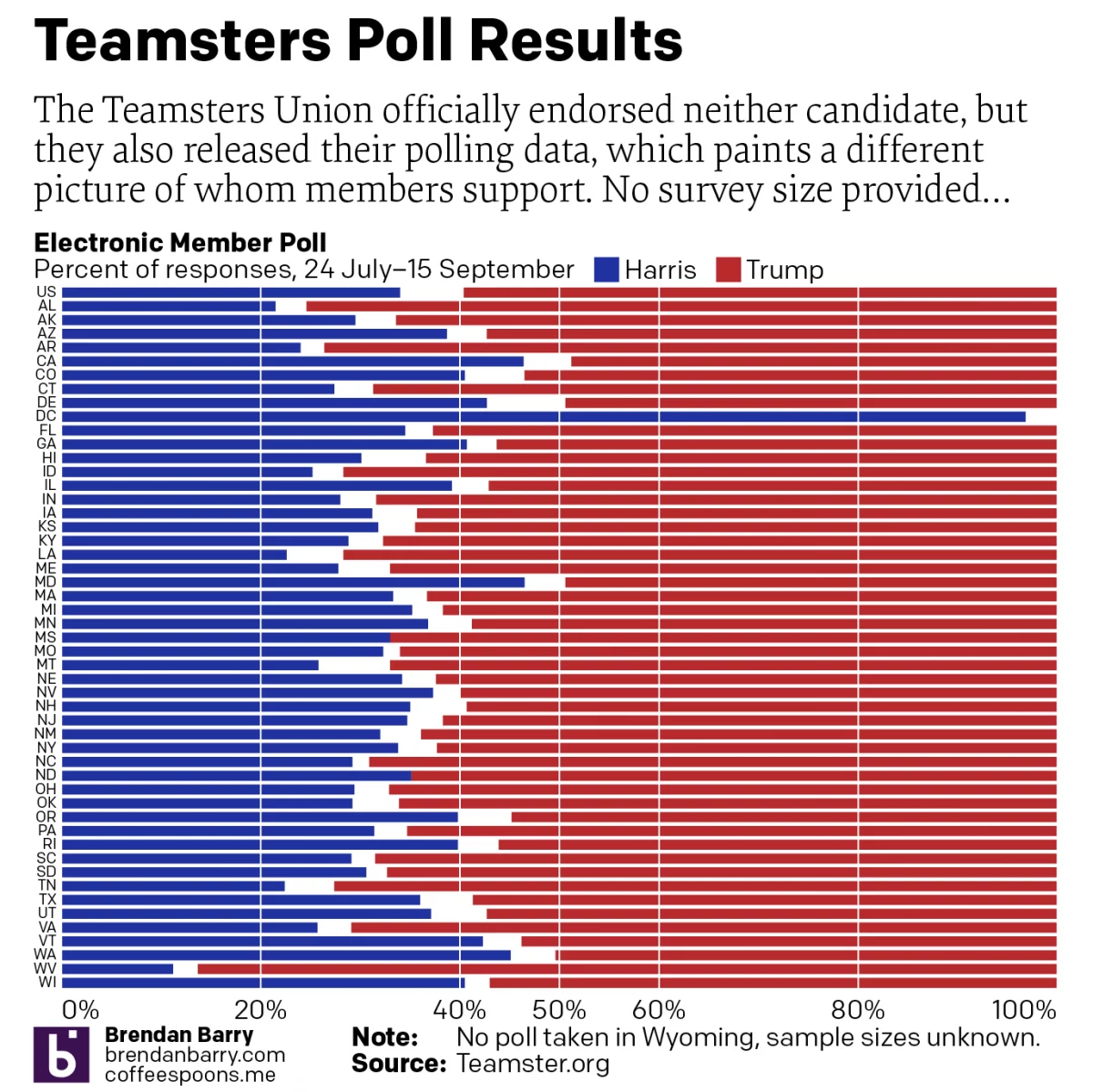

For Whom the Teamsters Poll Tolls

The Teamsters Union decided to officially endorse neither candidate in the 2024 US presidential election. Prior to their non-announcement announcement, however, the union surveyed its members and then released the polling data ahead of the announcement. Of course, the teamsters represent but a single union in a large and diverse country. More importantly, the survey…

-

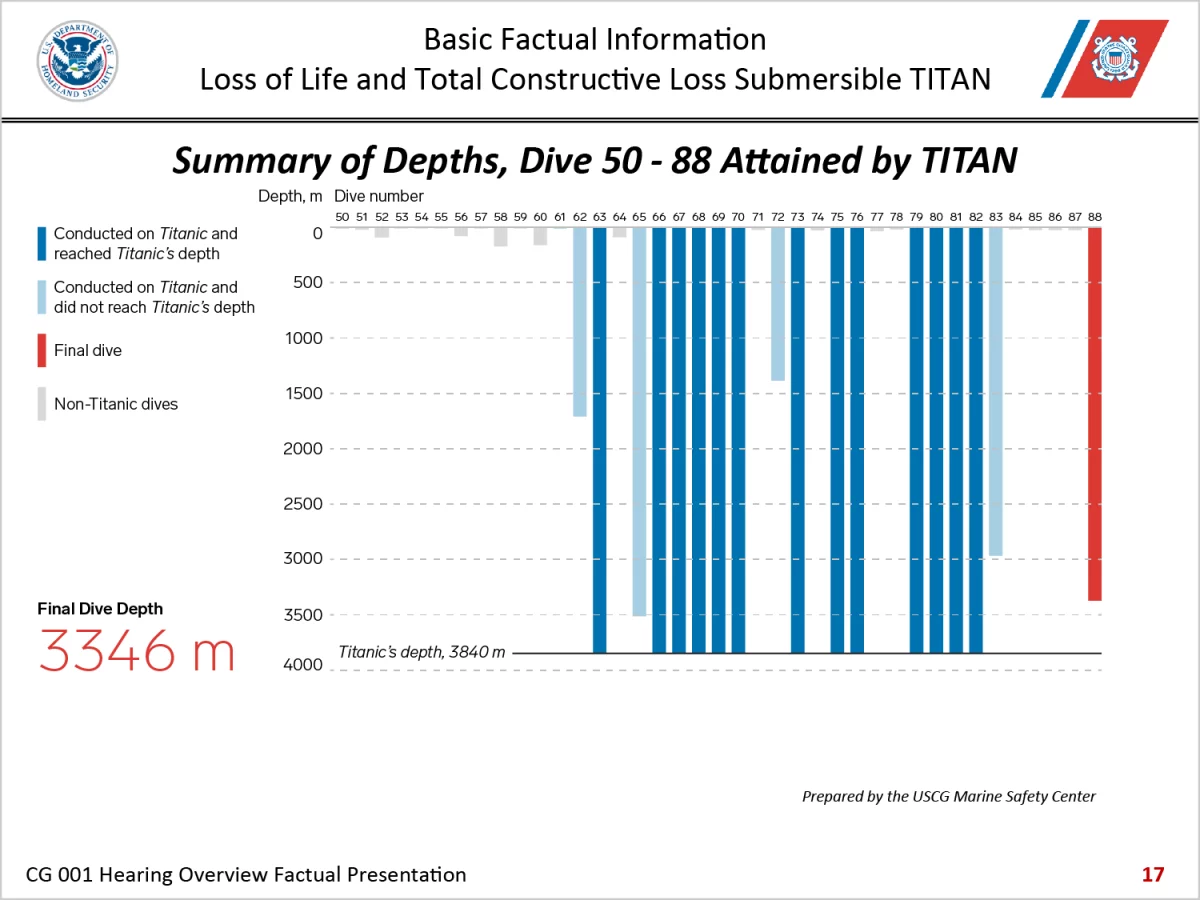

Three-dimensional Charts Are Back, Baby

I thought three-dimensional charts died back in the 2010s. Alas, here we are in 2024 and I have to discuss one once again. have been following the Titan Inquiry this week and the opening presentation included this gem of data visualisation. To be fair, I do not know how many designers, let alone specialist information…

-

To X or Not to X

As it happens, the Latino culture largely remains x’ed out on using the term Latinx, according to a new survey from Pew Research. The issue of supplanting Latino/Latina with Latinx as a gender neutral replacement—or as a complementary alternative—emerged in the general discourse in that oh-so-fun year of 2020 when everything went well. One common…

-

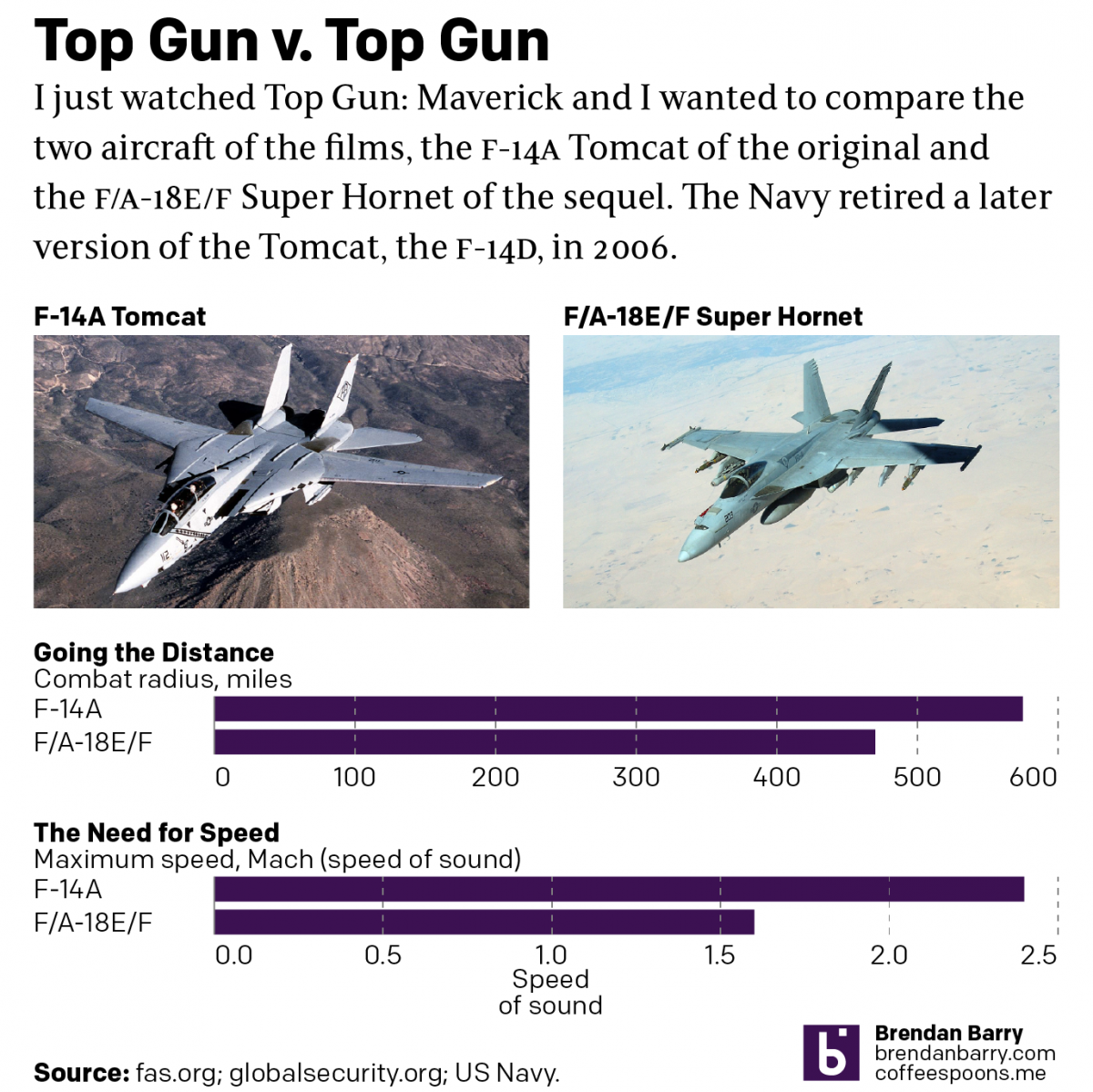

Top Gun

Last night I went to see Top Gun: Maverick, the sequel to the 1986 film Top Gun. Don’t worry, no spoilers here. But for those that don’t know, the first film starred Tom Cruise as a naval aviator, pilot, who flew around in F-14 Tomcats learning to become an expert dogfighter. Top Gun is the…