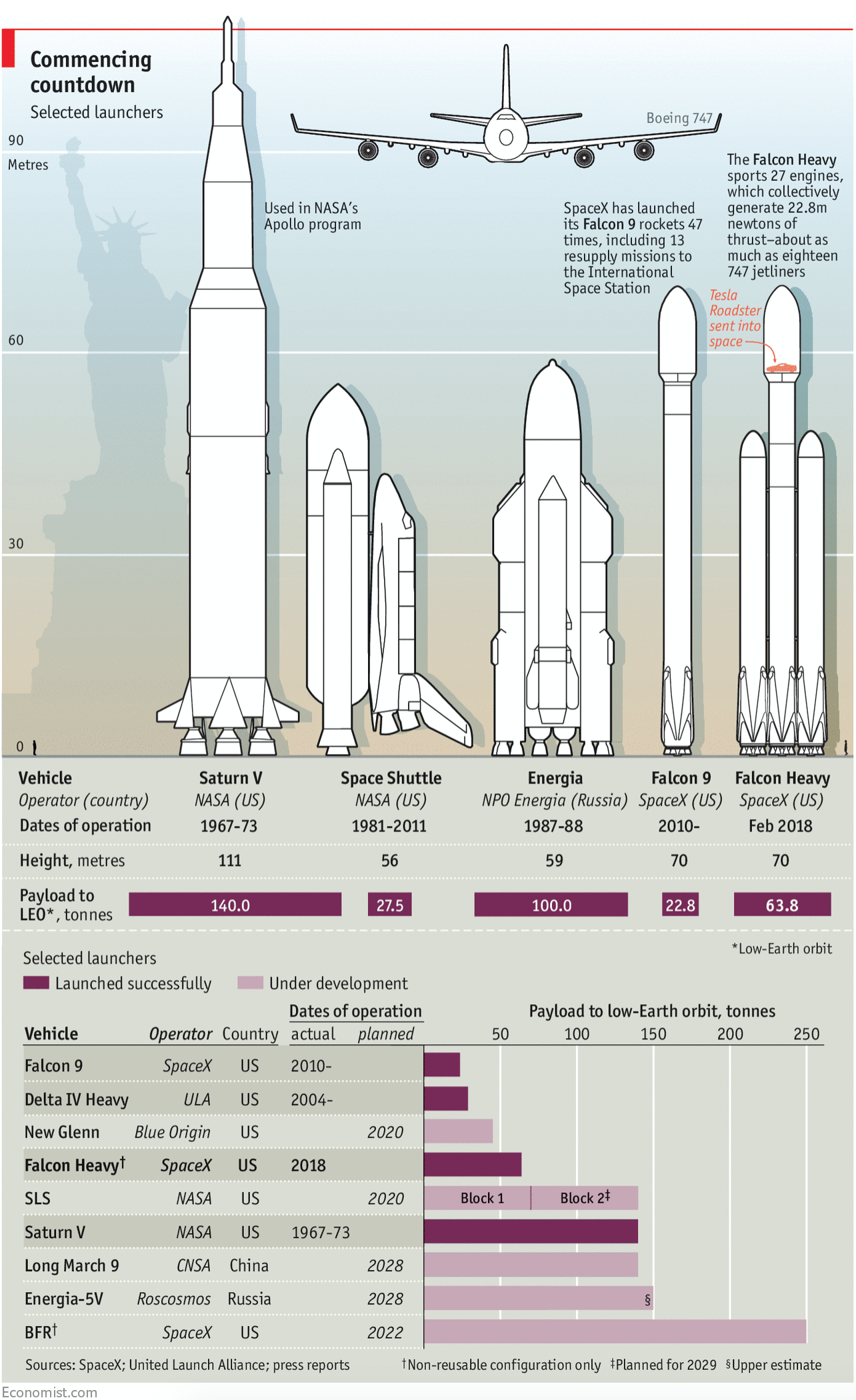

Yesterday SpaceX launched the Falcon Heavy rocket on its maiden voyage, and then recaptured several, though not all, of its reusable rockets. The Falcon Heavy represents the most powerful rocket available to mankind today, though NASA’s Saturn V of the Apollo programme era was considerably more powerful. That was all the stuff you could read in the news yesterday and today.

But how much more powerful? Thankfully we have the Economist who put together a nice graphic detailing not just the standard size comparisons of the Falcon series to the Saturn V and other famous rocket systems, e.g. the Space Shuttle and its boosters. The Economist graphic also adds information about the payload capabilities and timeframes for either historical operation or expected service dates.

From the illustrative side, there were three really nice touches. First, the faint Statue of Liberty to give the rocket height context to famous landmark buildings. Two, the little human figure on the left-hand side to give context to ourselves, these things are big. Three, the ridiculousness of the Saturn V is captured by having its peak break the top frame of the chrome or graphic device, i.e. the red bar, standard on Economist graphics.

Overall a solid piece. (Yes, I know these are liquid fueled.)

Credit for the piece goes to the Economist’s graphics team.