Category: Datagraphic

-

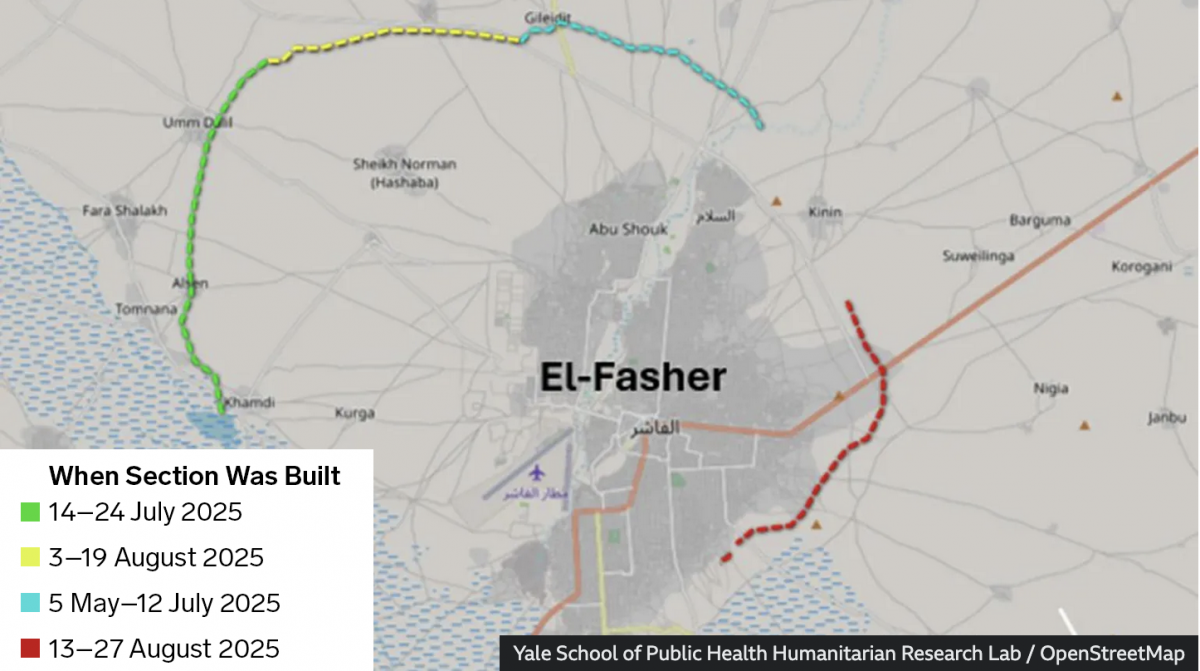

Sudan Side by Side

Conflict—a brutal civil war—continues unabated in Sudan. In the country’s west opposition forces have laid siege to the city of el-Fasher for over a year now. And a recent BBC News article provided readers recent satellite imagery showing the devastation within the city and, most interestingly, one of the most ancient of mankind’s tactics in…

-

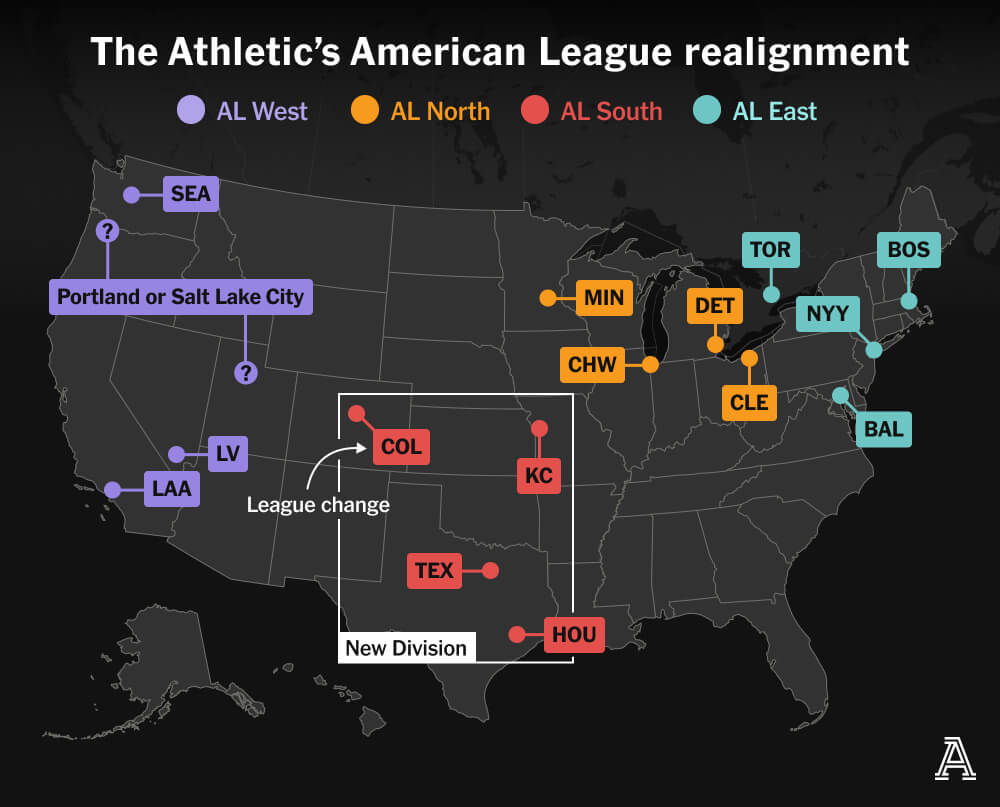

MLB’s Realignment

Last weekend, Major League Baseball Commissioner Rob Manfred created a mild furore when he discussed the sport’s looming expansion and how it would likely prompt a geographic realignment. I am old enough I still recall baseball’s two leagues—the American and National—organised into only two divisions—East and West. In the early 1990s, baseball expanded and created…

-

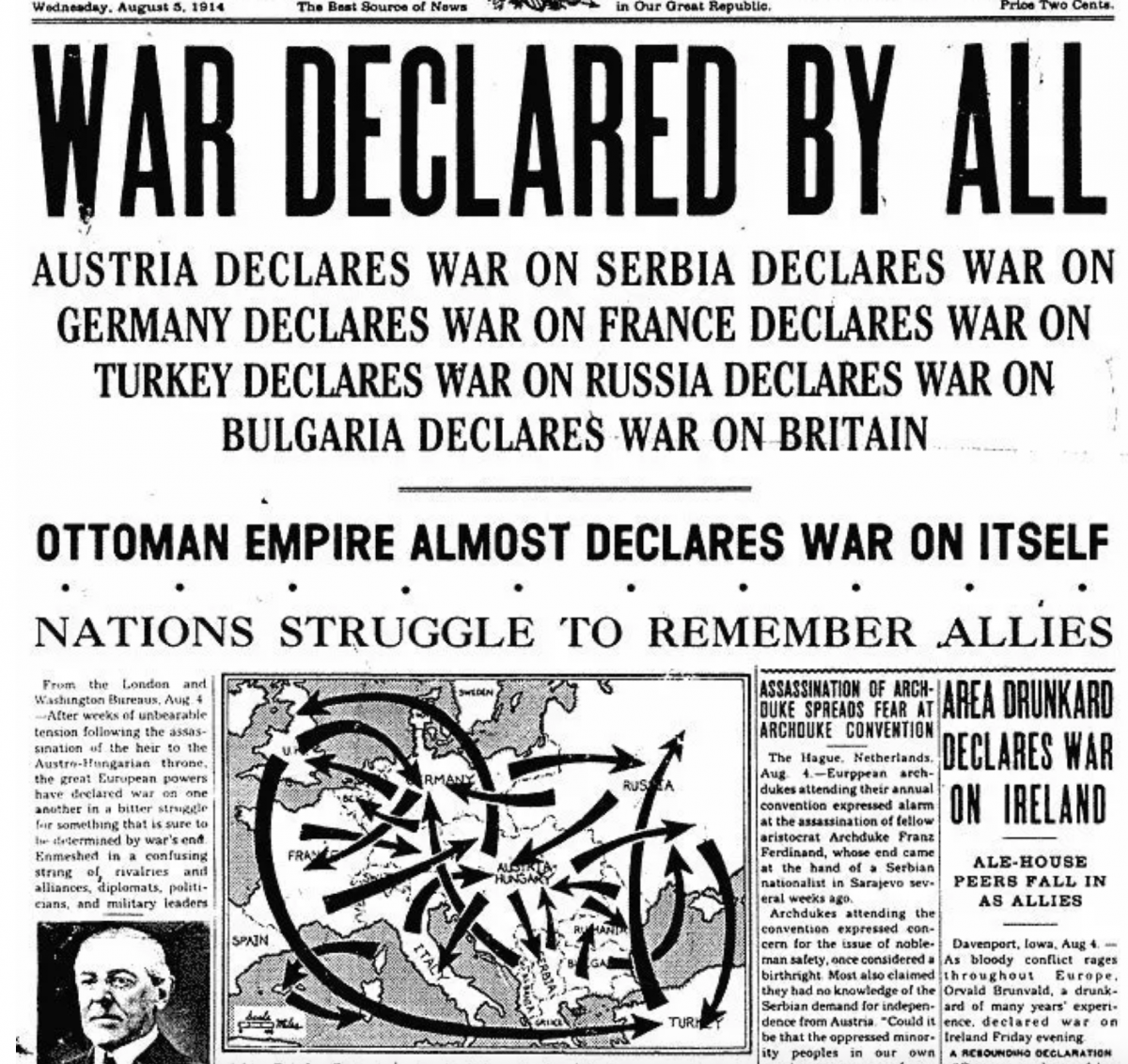

You Get a War, You Get a War, You Get a War…

A good friend of mine sent me this graphic earlier this week. The World Wars fascinate me—to be fair, most history does, and yes, that even includes the obligatory guy thinking of the Roman Empire—and I can see on my bookshelf as I type this post up my books on naval warships from World War…

-

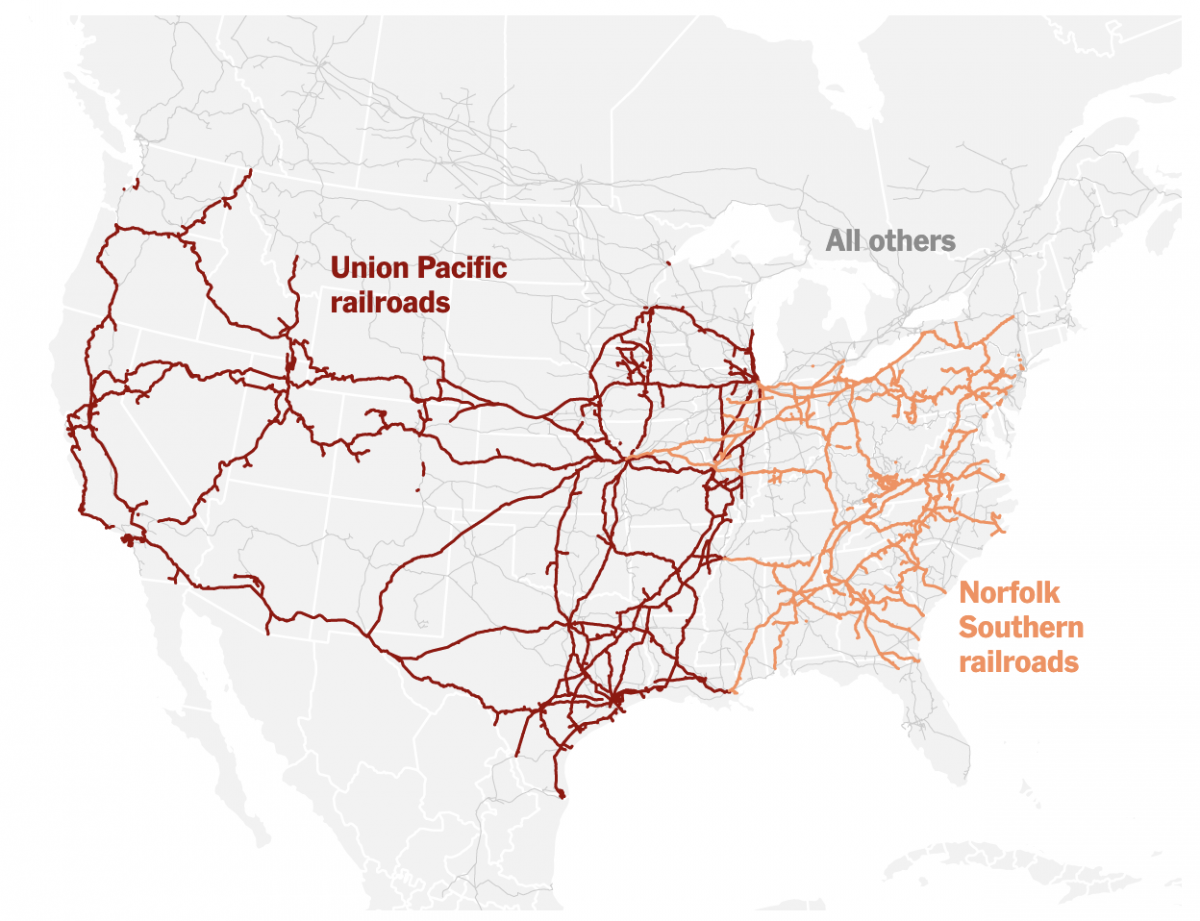

Truly Transcontinental

Last week two of the largest American freight railroads agreed to a merger with Union Pacific purchasing Norfolk Southern. Railroads have long played an important part in the history of the United States, from the Second Industrial Revolution to settlement and development of the West, through to the time zones in which we live and…

-

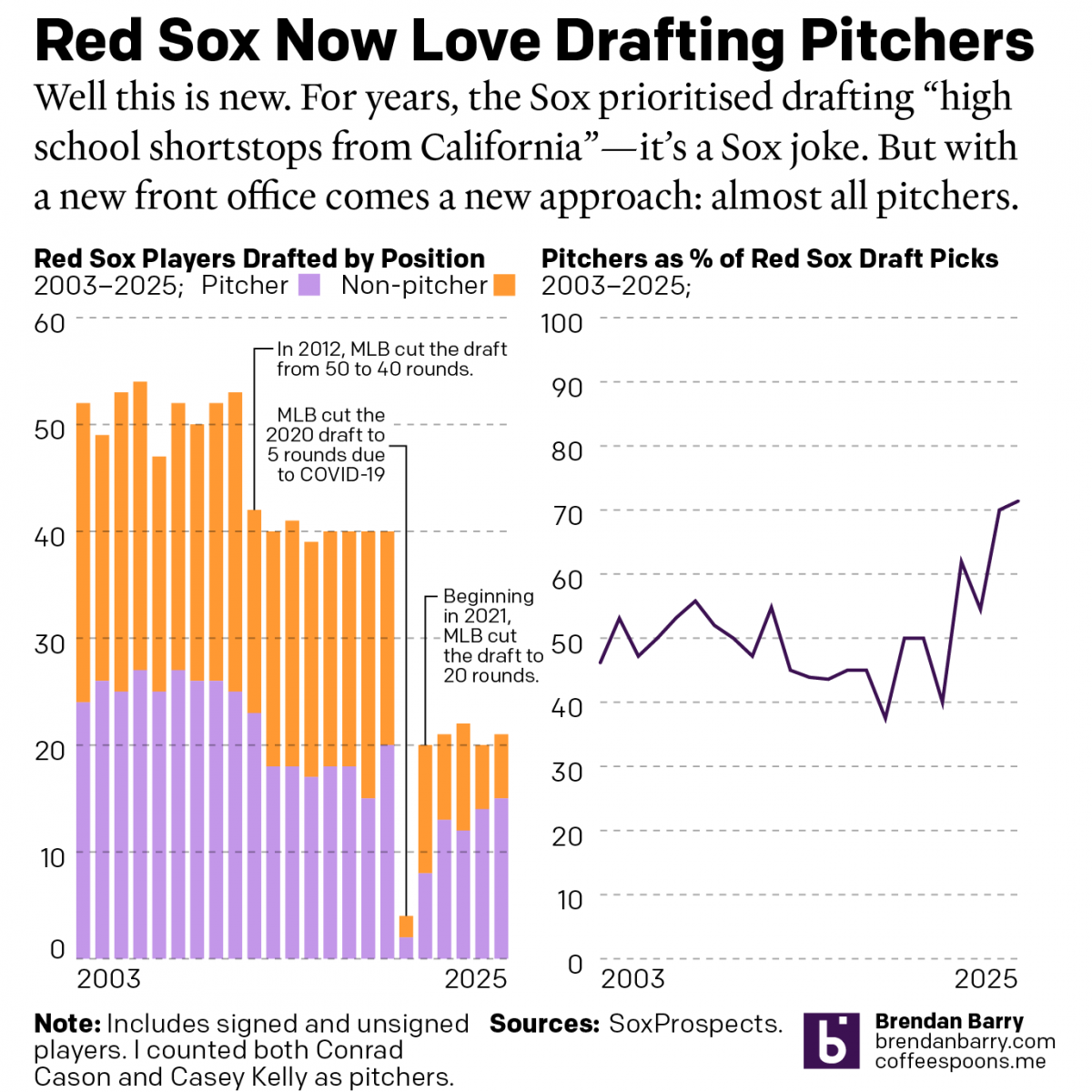

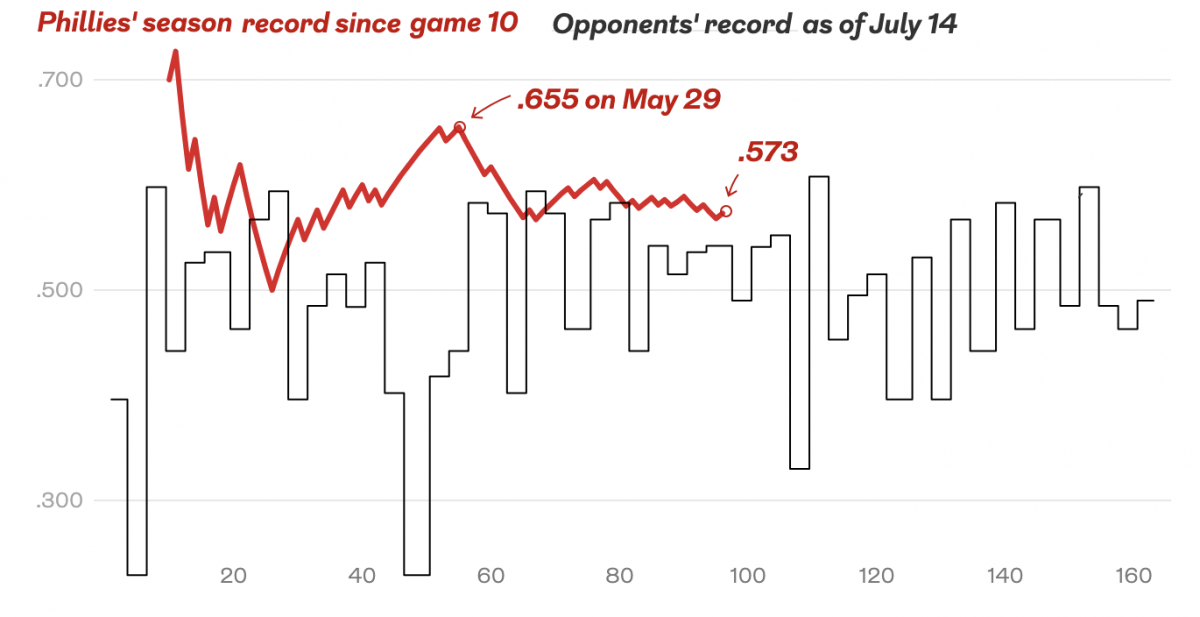

Bring on the Beantown Boys

For my longtime readers, you know that despite living in both Chicago and now Philadelphia, I am and have been since way back in 1999, a Boston Red Sox fan. And this week, the Carmine Hose make their biennial visit down I-95 to South Philadelphia. And I will be there in person to watch. This…

-

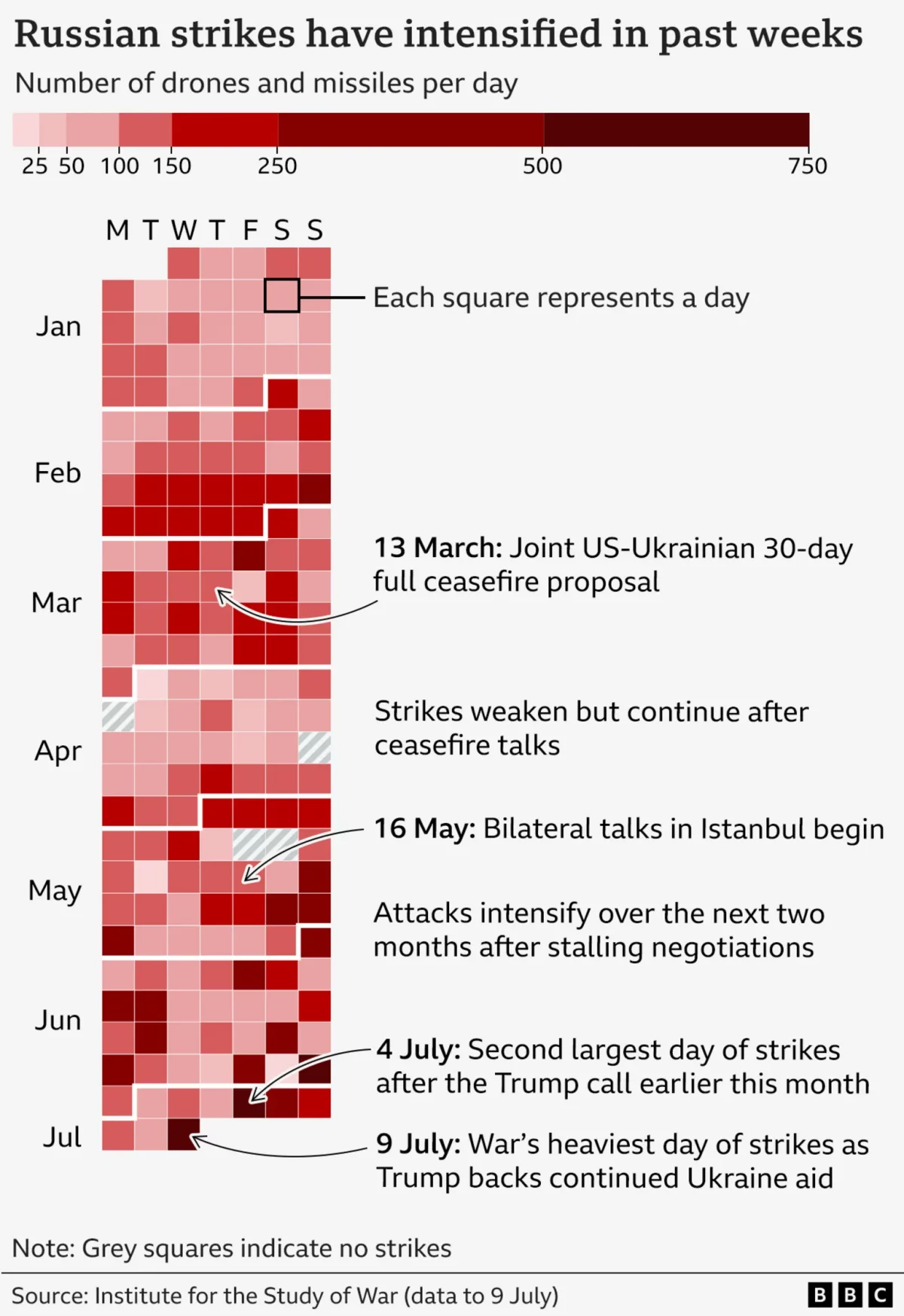

It’s Raining Drones

Last Friday the BBC published an article about the US’ resumption of supplying military assistance to Ukraine in its defence of Russia’s invasion. But in that article, the author referenced the increased intensity of Russian drone and missile strikes on Ukraine over that week. To show the intensity, the BBC included this graphic, which incorporates…

-

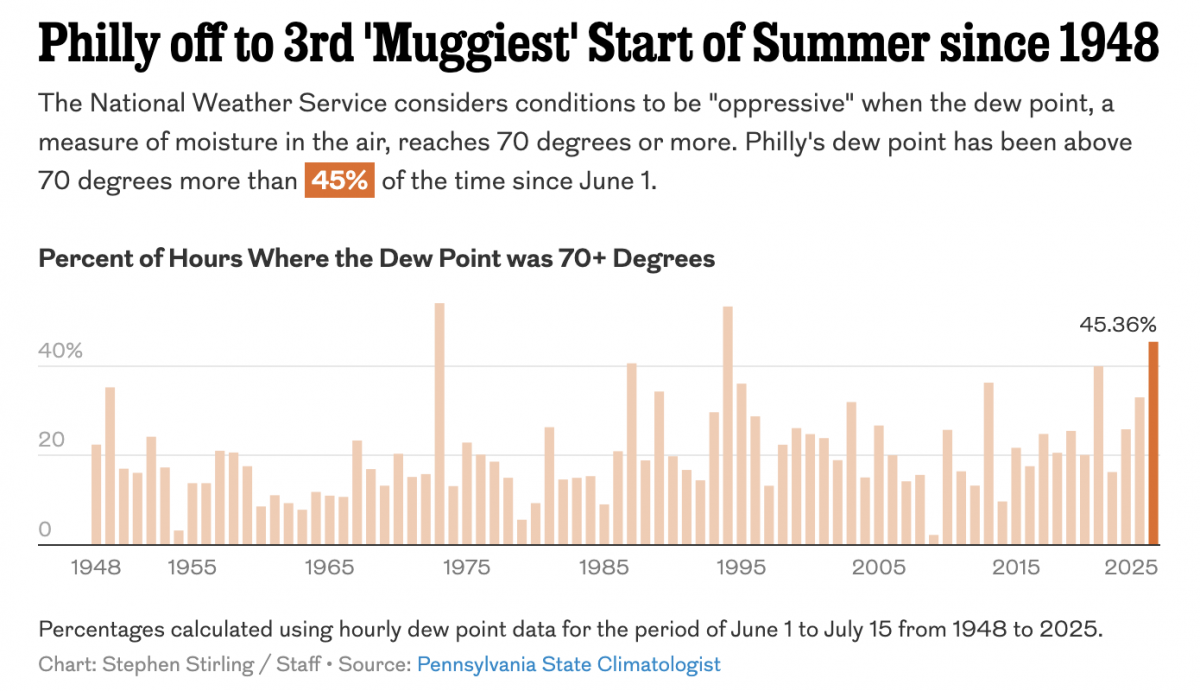

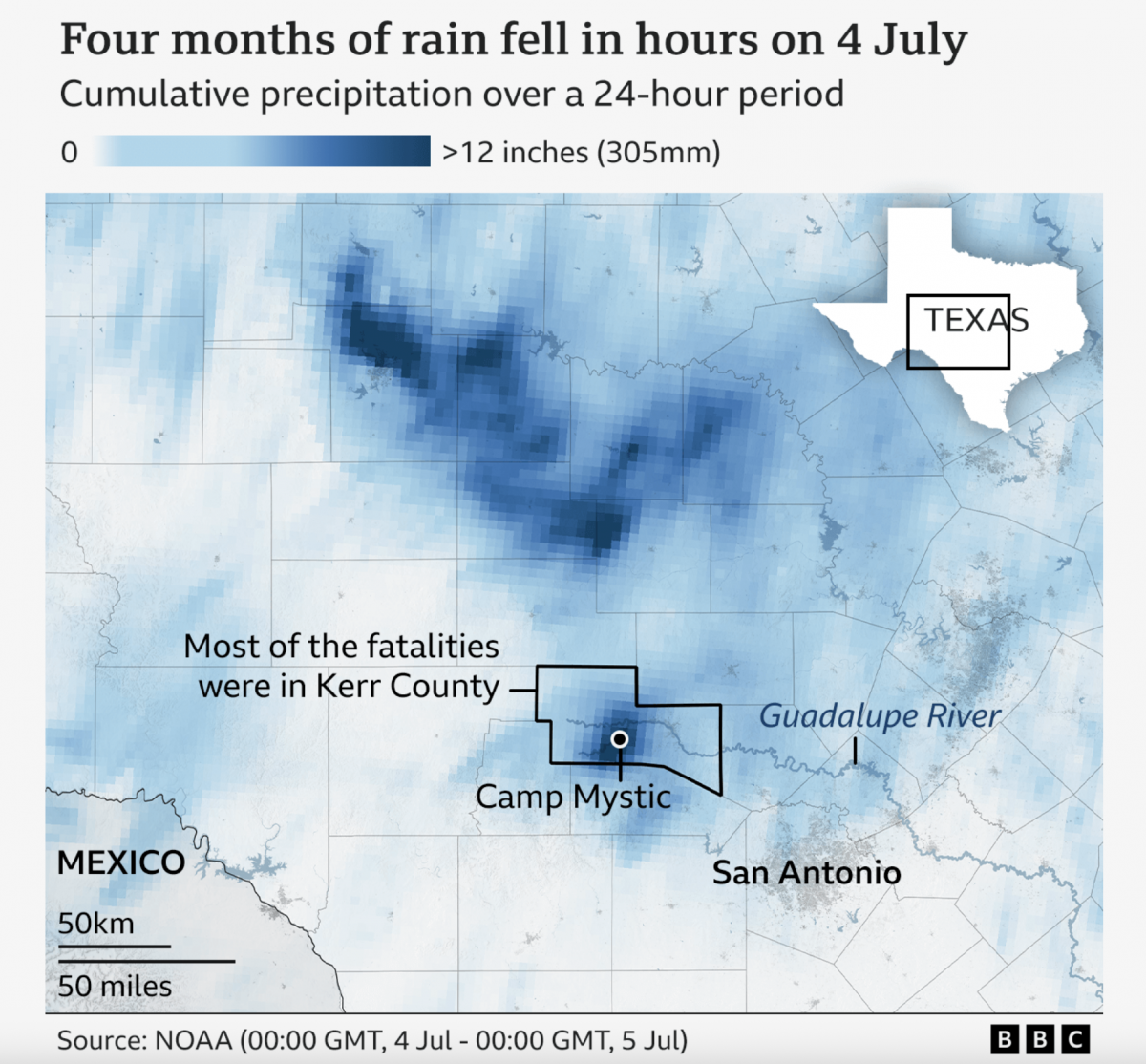

A Warming Climate Floods All Rivers

Last weekend, the United States’ 4th of July holiday weekend, the remnants of a tropical system inundated a central Texas river valley with months’ worth of rain in just a few short hours. The result? The tragic loss of over 100 lives (and authorities are still searching for missing people). Debate rages about why the…

-

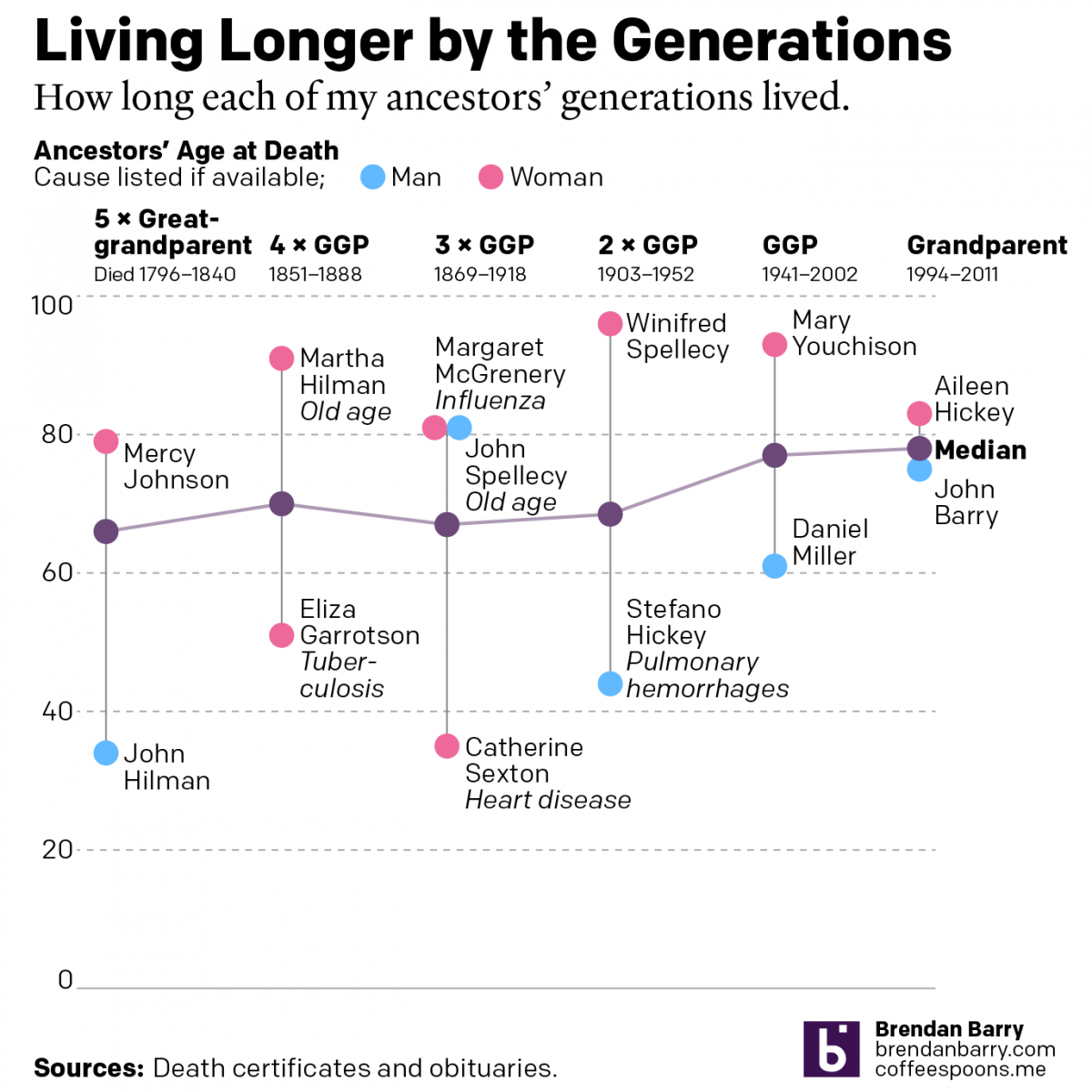

Living Longer by the Generations

Last weekend was Easter—for both the Catholics and the Orthodox—and I visited the Appalachian ancestral home of the Carpatho–Rusyn side of my family. Before leaving town I drove up to the old cemetery on a hill overlooking the old church and the Juniata River to pay my respects to those who came before me and…