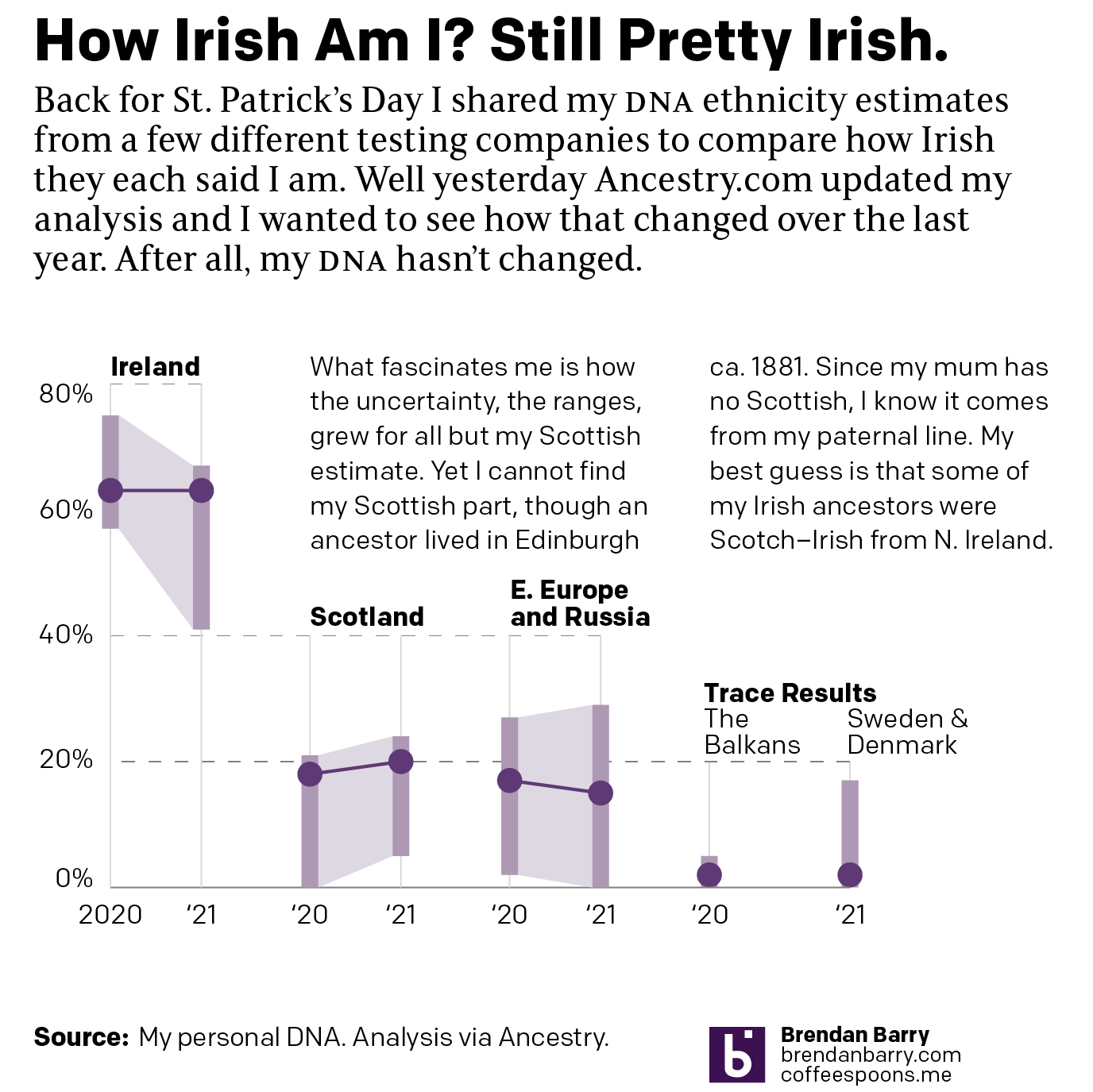

As many long-time readers know, I was long ago bitten by the genealogy bug and that included me taking several DNA tests. The real value remains in the genetic matches, less so the ethnicity estimates. But the estimates are fun, I’ll give you that. Every so often the companies update their analysis of the DNA and you will see your ethnicity results change. I wrote about this last year. Well yesterday I received an e-mail that this year’s updates were released.

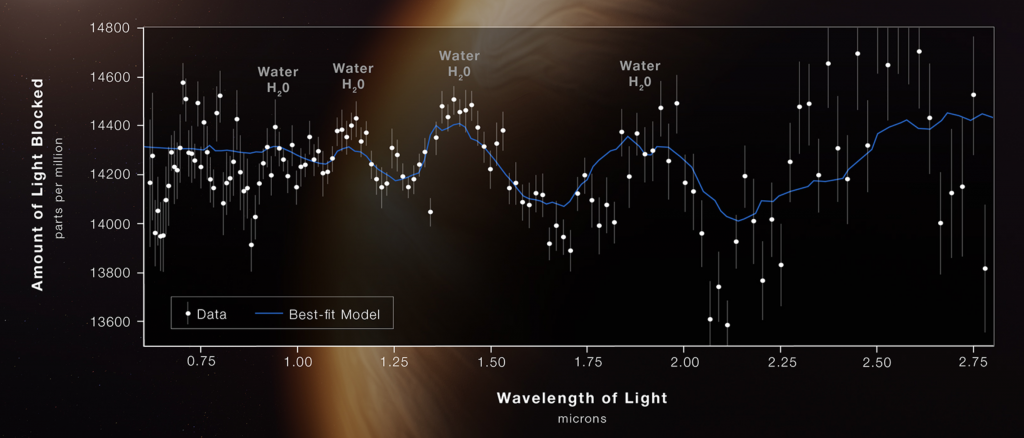

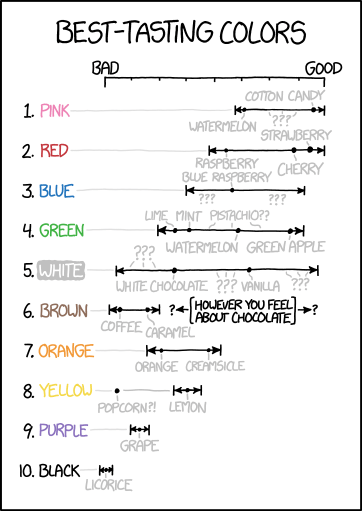

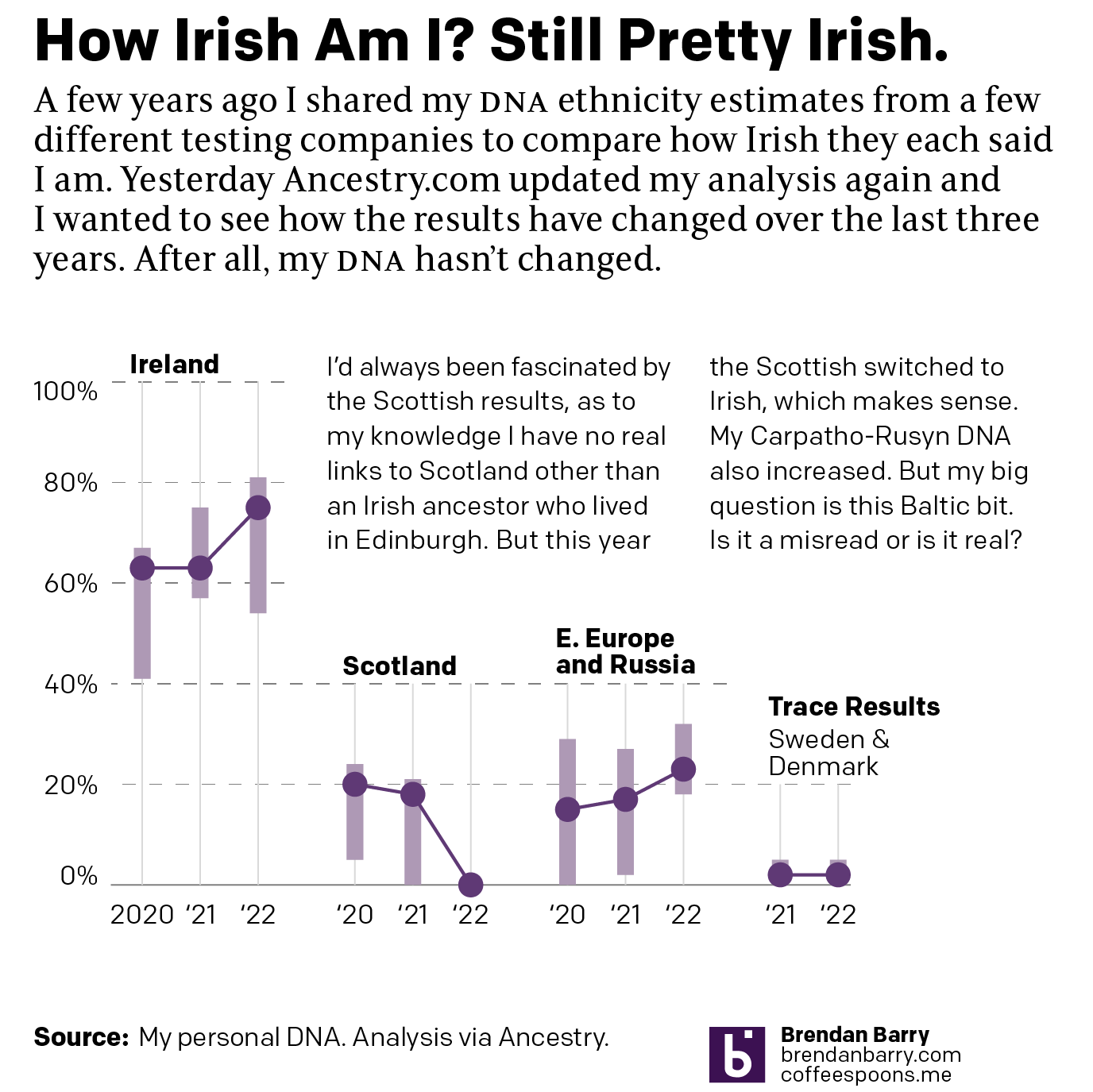

So you get another graphic.

The clearest change is that the Scottish bit has disappeared. How do you go from nearly 20% Scottish to 0%? Because population groups in the British isles have mixed for centuries. When the Scottish colonised northern Ireland, they brought Scottish DNA with them. And as I am fairly certain that I have Irish ancestors from present-day Northern Ireland, it would make sense that my DNA could read as Scottish. But clearly with the latest analysis, Ancestry is able to better point to that bit as Irish instead of Scottish. And this shouldn’t surprise you or me, because those purple bars represent their confidence bands. I might have been 20% Scottish, but I also could have been reasonably 0% Scottish.

Contrast that to the Carpatho-Rusyn, identified here as Eastern European and Russian. That hovers around 20%, which makes sense because my maternal grandfather was 100% Carpatho-Rusyn—his mother was born in the old country, present-day Slovakia. We inherit 50% of our DNA from each of our parents, but because they also inherit 50%, we don’t necessarily inherit exactly 25% from our grandparents and 12.5% from our great-grandparents, &c.

But also note how the confidence band for my Carpatho-Rusyn side has narrowed considerably over the last three years. As Ancestry.com has collected more samples, they’re better able to identify that type of DNA as Carpatho-Rusyn.

Finally we have the trace results. Often these are misreads. A tiny bit of DNA may look like something else. Often these come and go each year with each update. But the Sweden and Denmark bit persisted this year with the exact same values. If I compare my matches, my paternal side almost always has some Swedish and Danish ethnicity, not so for my maternal side. And importantly, those matches have more. Remember, because of that inheritance my matches further up on my tree should have more DNA, and that holds true.

That leads me to believe this likely isn’t a misread, but rather is an indication that I probably have an ancestor who was from what today we call Sweden or Denmark. Could be. Maybe. But at 2%, assuming the DNA all came from one person, it’s probably a 4th to a 6th great-grandparent depending on how much I and my direct ancestors inherited.

Clearly there’s more work to do.