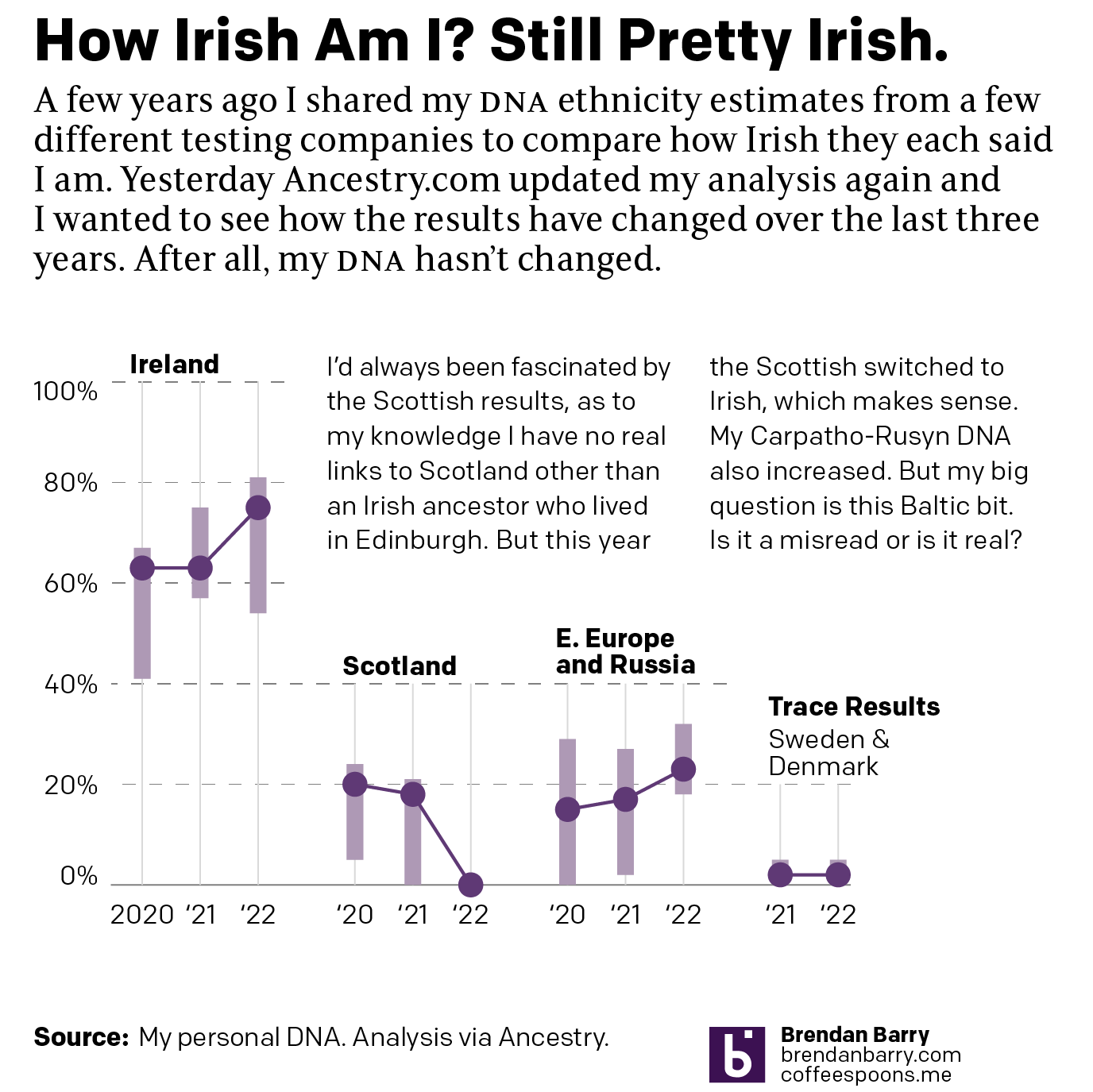

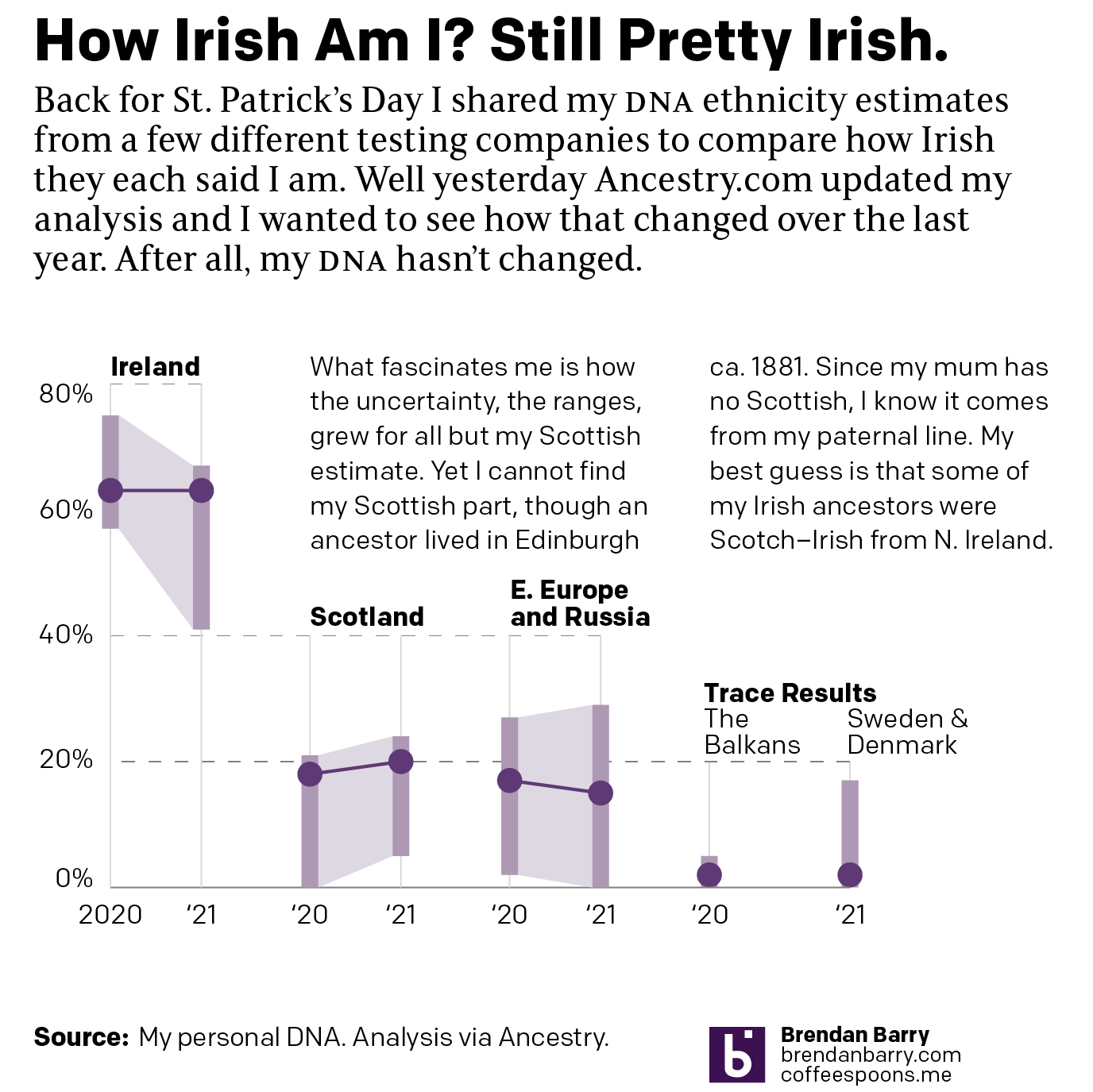

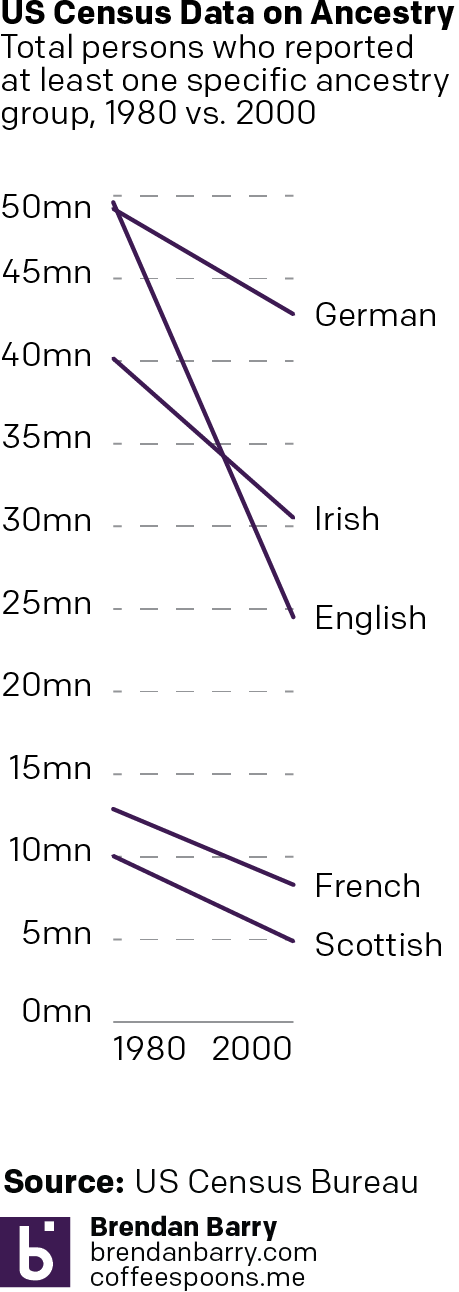

Yesterday was Saint Patrick’s Day and those who have followed me at Coffeespoons—or more generally know me—are well aware that my background is predominantly Irish. Those same people probably also know of my keen interest in genealogy. And that’s what today’s post is all about.

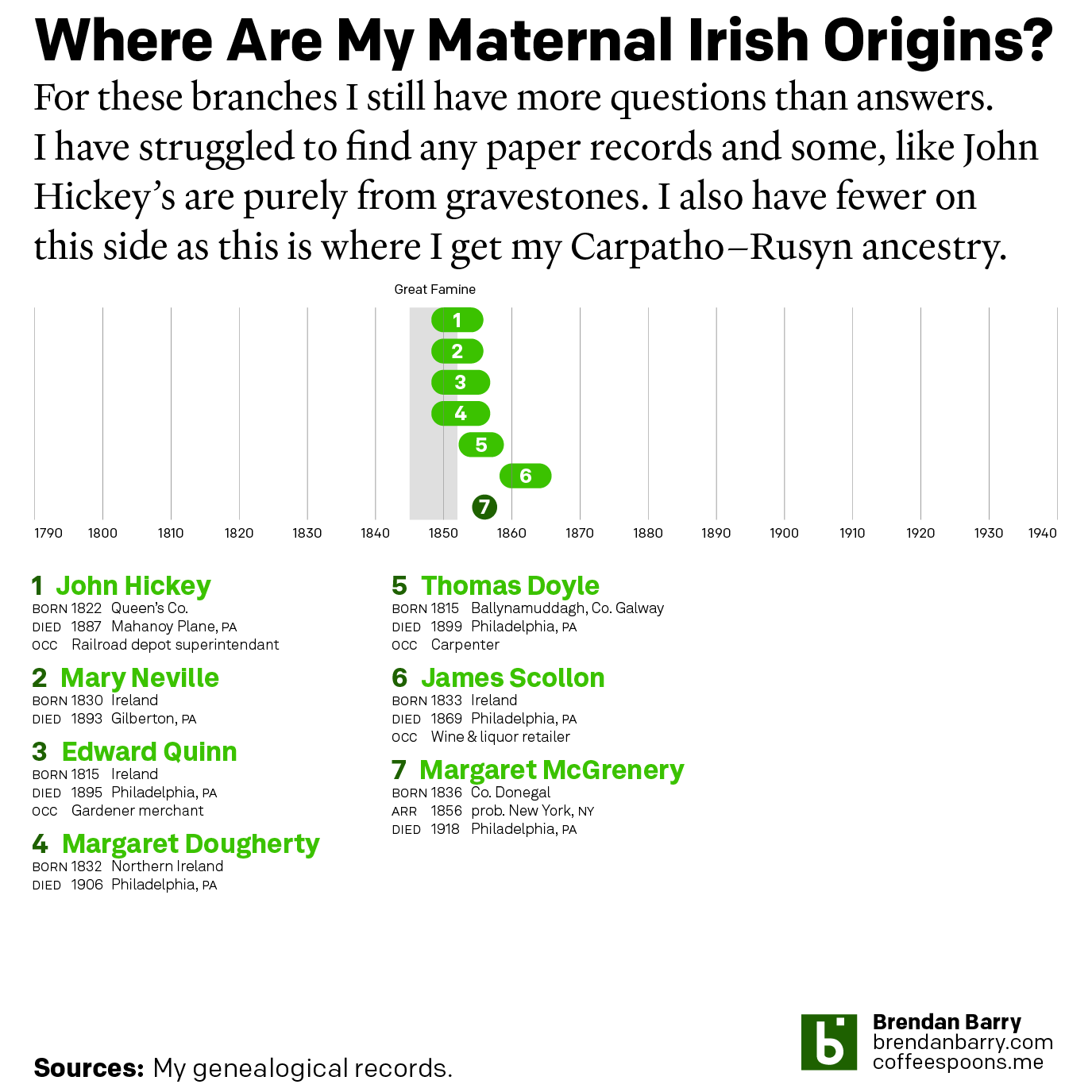

Irish genealogy is difficult because of the lack of records and lack of record access. My struggle is often in connecting an ancestor to a specific place in Ireland, necessary for any work to identify baptism, marriage, or death records. Starting with my maternal lines, it’s easy to see how ancestors were from “Ireland”, but I’ve been able to place precious few into a specific geographic context.

Thomas Doyle is the only ancestor I can place into a specific parish, and he wasn’t the key person who allowed it. For those interested in genealogy, it’s always worthwhile to investigate siblings, cousins, aunts, uncles, and sometimes even friends and neighbours because they often can provide clues, as it did in the case of the Doyles.

Sometimes you also need to step outside and get lost in a cemetery. I took a drive one weekend before the pandemic to find the graves of John Hickey and his family. Until that point, I knew nothing about the origins of him or his wife. Luckily his gravestone went one step beyond Ireland and stated he was born in Queen’s County, now County Laois. But I’ve still found no evidence of where in Laois he was born and so tracking the rest of his family is difficult, perhaps impossible.

Furthermore, you can also see that I have little specific information about when these ancestors all arrived. None were present in the 1850 US Census, so we can reasonably work from a starting hypothesis that they arrived after 1850 and then when each had children documented born in the US—or the rarer occasion of a US marriage record—we can reasonably assume they arrived between 1850 and the child’s birth.

On my maternal side there is a lot of work to do, which belies all the effort put into just getting this far over the last decade plus. Contrast that to my paternal side.

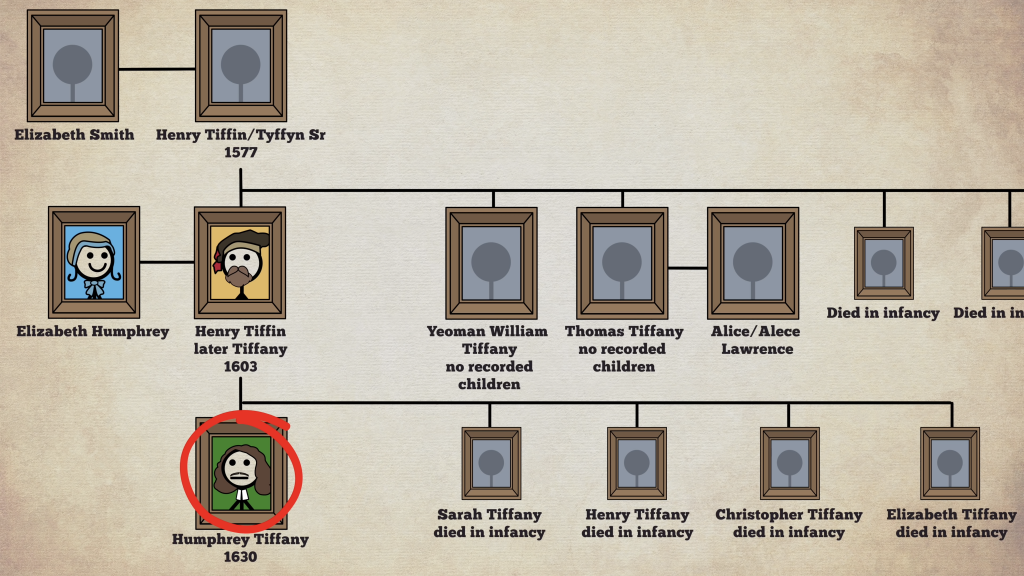

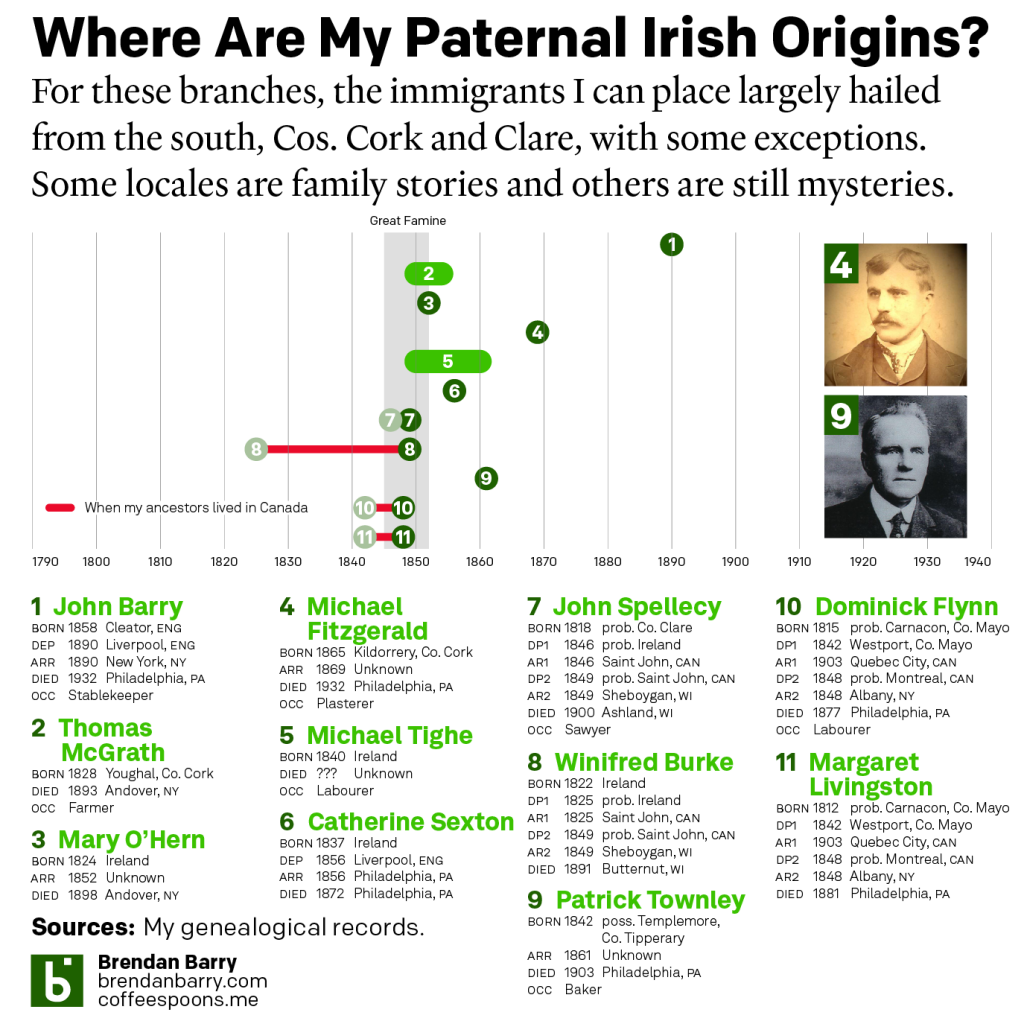

Here I have more Irish ancestors to investigate and I’m fortunate that I have more of an American paper trail, which when stitched together allowed me to get snippets of counties of birth or marriage, which, with some helpfully uncommon names, allowed me to dial in on specific parishes and towns. In other cases, my Irish ancestors first settled in Canada or the United Kingdom, which have much better preserved records. And finally a few have had family histories written and documented elsewhere, which allowed me to check the paper trail and validate the work.

And obviously when dealing with people in the mid-19th century, we don’t have a lot of photography and I’m lucky to have found a website—no longer extant, rest in peace Geocities—that had photos of my ancestors and a cousin over in Ireland who had a few photos sent my ancestors to their relations—though we’re not sure how they’re related, another story for another day—that I can put two faces to 18 names of direct Irish immigrant ancestors.

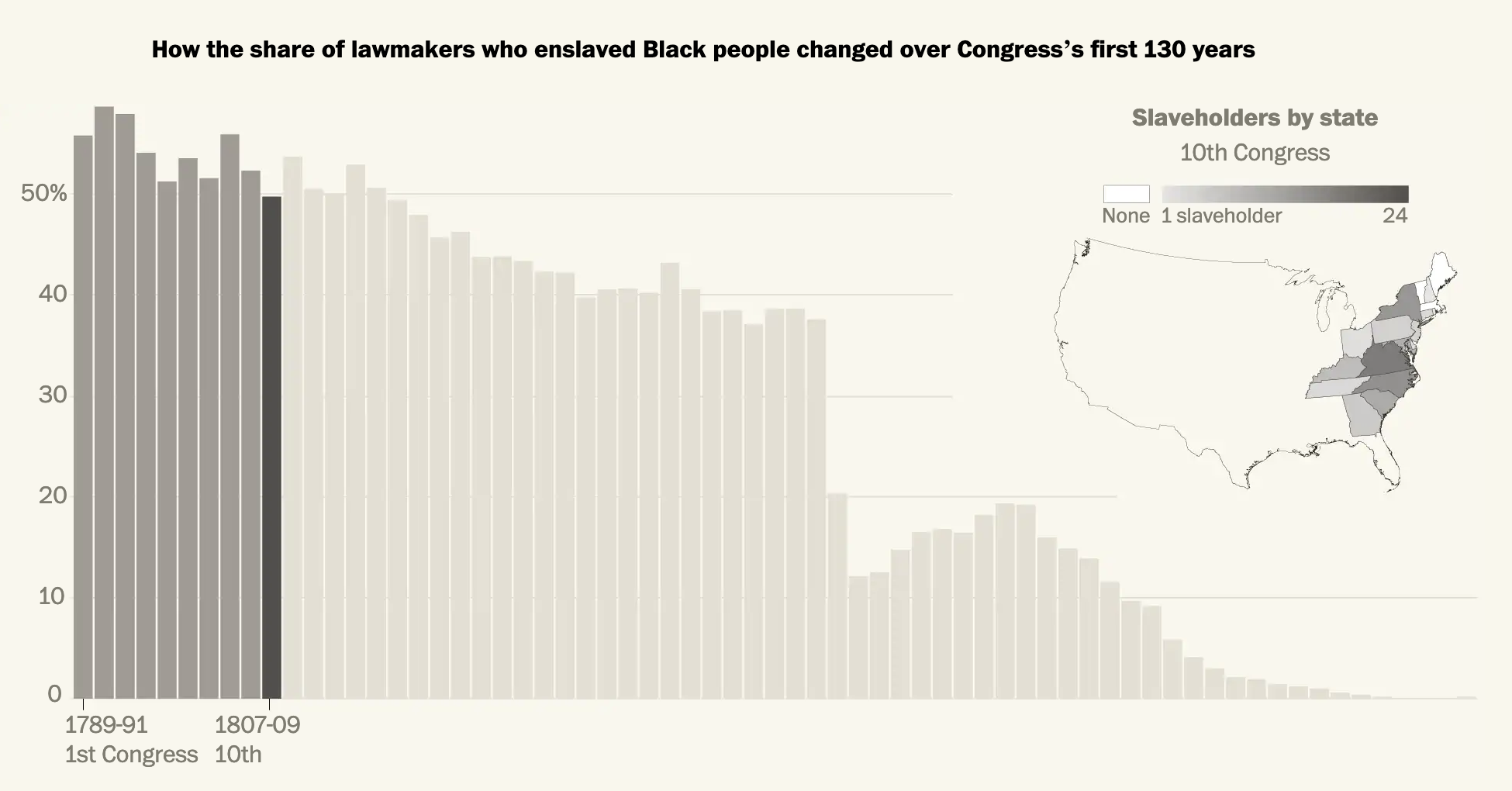

And of course the thing of note for all these people is that grey bar in the middle of the timeline: the Great Famine. In a roughly seven year period, over one million Irish died in Ireland and another over one million people left Ireland for places like the UK, Canada, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, among other places. It’s partly the reason for the massive Irish diaspora and why Saint Patrick’s Day is celebrated globally.

You can see some of my Irish ancestry is clearly unrelated, at least directly, to the Great Famine. But when you dig a bit deeper, you see the indirect connection. That John Barry who was an Irish stablekeeper who left Edinburgh for Philadelphia via Liverpool and New York, he was born to Irish parents in Cumberland, England—now Cumbria—who married there just after the end of the Great Famine and for whom there is no record prior to the Great Famine. In other words, they likely fled their home for fear of starvation and then in one generation their children all left England for America.

Irish genealogy is incredibly difficult, but it can also be incredibly rewarding. But you have have to keep digging and digging for even sometimes the shallowest roots.

Credit for the piece is mine.