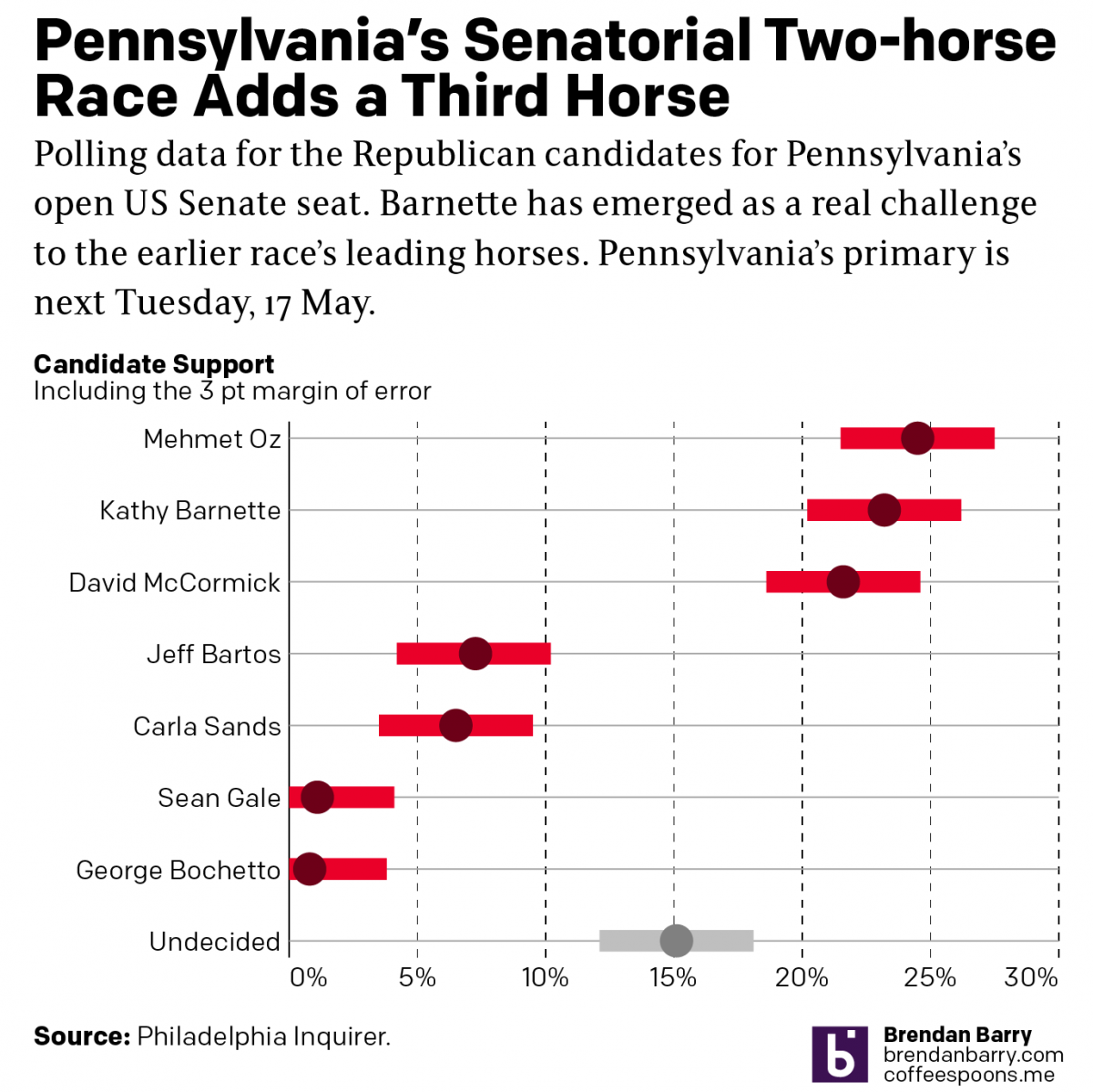

Tag: Philadelphia Inquirer

-

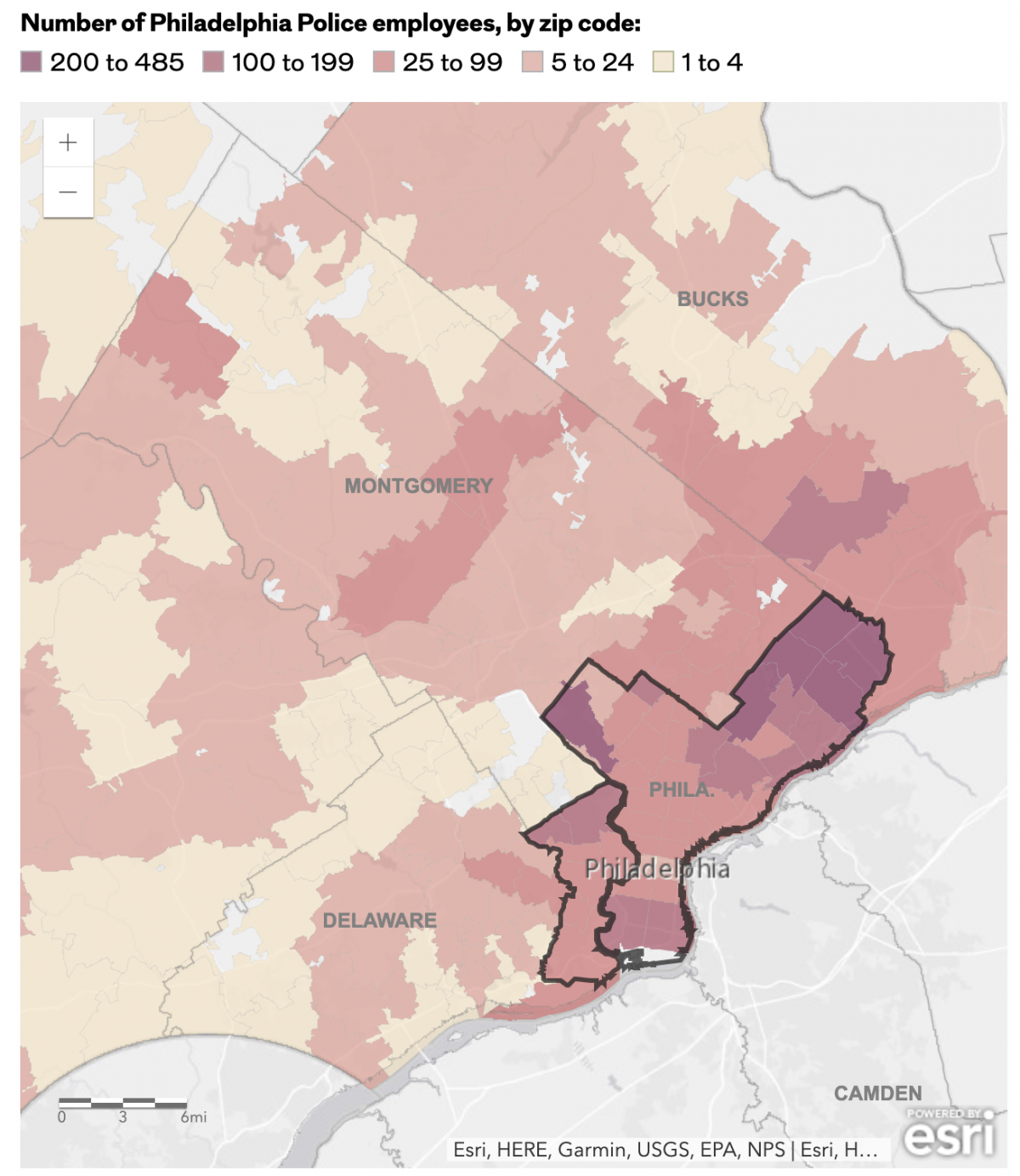

The Philadelphia Beat is Pretty Big

Early last week I read an article in the Philadelphia Inquirer about where the city’s police officers live, an important issue given the city’s loose requirement they reside within the city limits. Whilst most do, especially in the far Northeast, the Northwest, and South Philadelphia, a significant number live outside the city. (The city of…

-

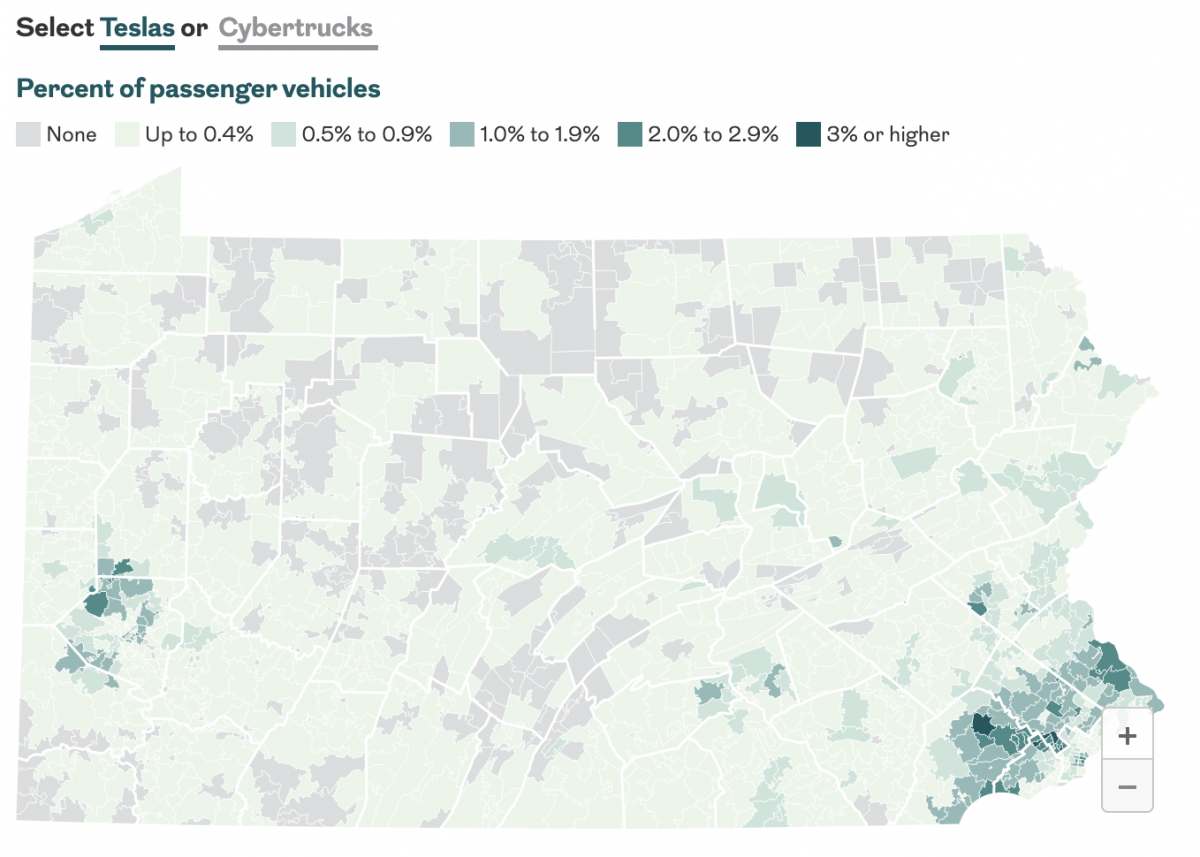

Baby You Can Drive My Car

Last month the Philadelphia Inquirer published an article examining the geographic distribution of Teslas and Cybertrucks and whether or not your car is liberal or conservative. The interactive graphics focused more on a sortable table, which allowed you to find your vehicle type. The sortable list offers users option by brand and body type—not model.…

-

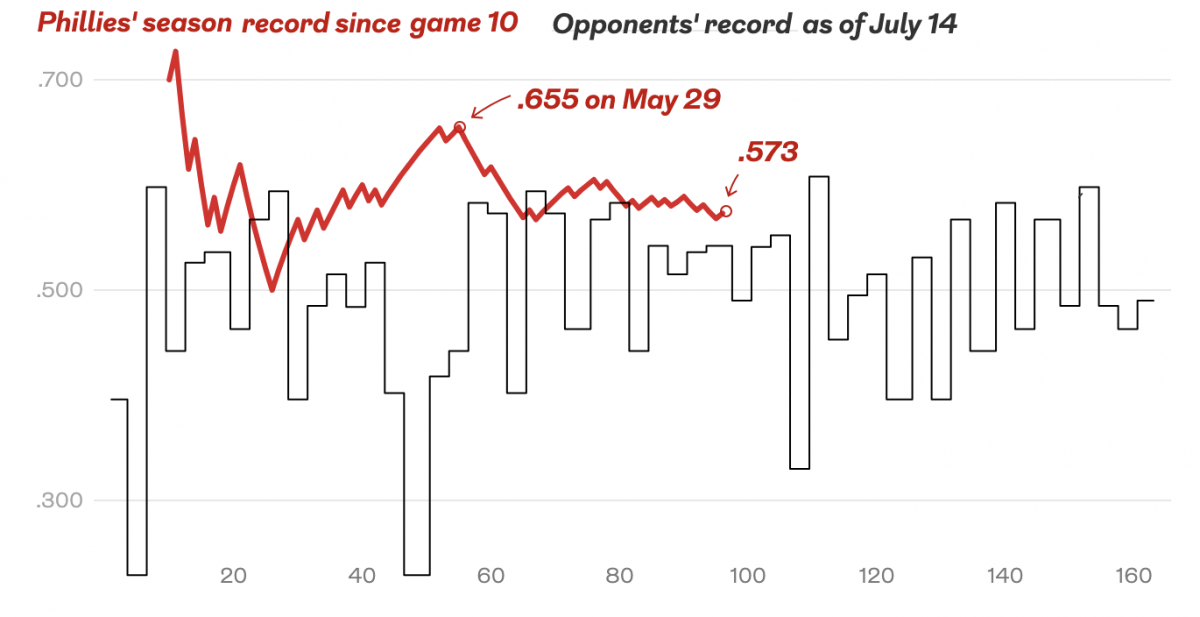

Bring on the Beantown Boys

For my longtime readers, you know that despite living in both Chicago and now Philadelphia, I am and have been since way back in 1999, a Boston Red Sox fan. And this week, the Carmine Hose make their biennial visit down I-95 to South Philadelphia. And I will be there in person to watch. This…

-

Cavalcante Captured

Well, I’ve had to update this since I first wrote, but had not yet published, this article. Because this morning police captured Danelo Cavalcante, the murderer on the lam after escaping from Chester County Prison, with details to follow later today. This story fascinates me because it understandably made headlines in Philadelphia, from which the…

-

A New Downtown Arena for Philadelphia?

I woke up this morning and the breaking news was that the local basketball team, the 76ers, proposed a new downtown arena just four blocks from my office. The article included a graphic showing the precise location of the site. For our purposes this is just a little locator map in a larger article. But…

-

Legendary Adjustments

The other day I was reading an article about the coming property tax rises in Philadelphia. After three years—has anything happened in those three years?—the city has reassessed properties and rates are scheduled to go up. In some neighbourhoods by significant amounts. I went down the related story link rabbit hole and wound up on…