Well, it’s Friday. We made it to the weekend. So here’s a nice Venn diagram from Indexed that captures that guy we all know.

Credit for the piece goes to Jessica Hagy.

For the last two days I have been writing about the Fort Pitt Museum and some infographics, environmental graphics, diagrams, and dioramas that help explain the strategic value and thus history behind the peninsula at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers. In particular, we looked at Fort Duquesne, the French attempt to fortify the position, and then Fort Pitt, the far more successful British attempt.

But a fortress without weaponry is like a snapping turtle without a sharpened beak. And once the fortifications were built, the British began moving in artillery pieces and hundreds of soldiers to defend their claim on the land. Local Native American tribes invited the British in and to station soldiers, but relations soured after a few years when it became clear the British, unlike the French, were more interested in settling the land.

In 1763, Native American discontent coalesced around Pontiac, an Ottawa warrior chief, who directed the outrage into violent actions in the western colonial lands. Pontiac’s War had begun. The British, recently victorious over the French, suffered several defeats as Native American forces took several British forts and raided settlements killing unknown numbers of settlers.

At the forks of the Ohio, local Native Americans besieged Fort Pitt. For two months, Fort Pitt was cut off from resupply and local settlers, who had poured into the fort, even took up arms. But the biggest weapons the British had were the artillery at the fortress.

Though it should be noted this was the incident during which a small smallpox outbreak occurred amongst the settlers and British military forces used smallpox infected blankets as gifts to the Native Americans. In later letters, this tactic was commended by senior British military officials. However, the efficacy of the action from a military perspective is debatable at best.

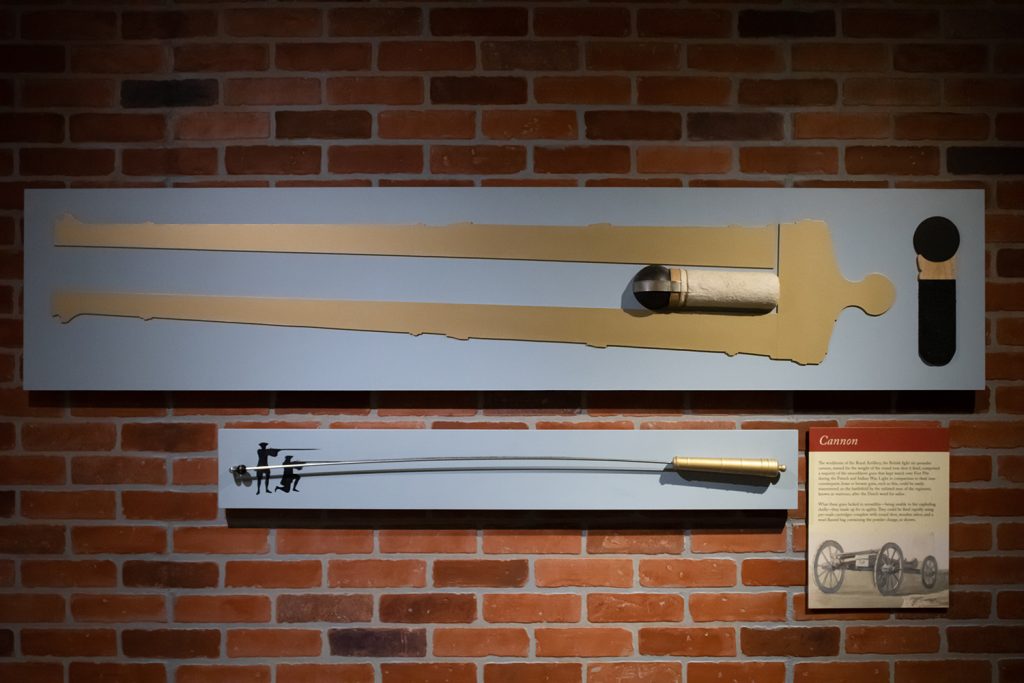

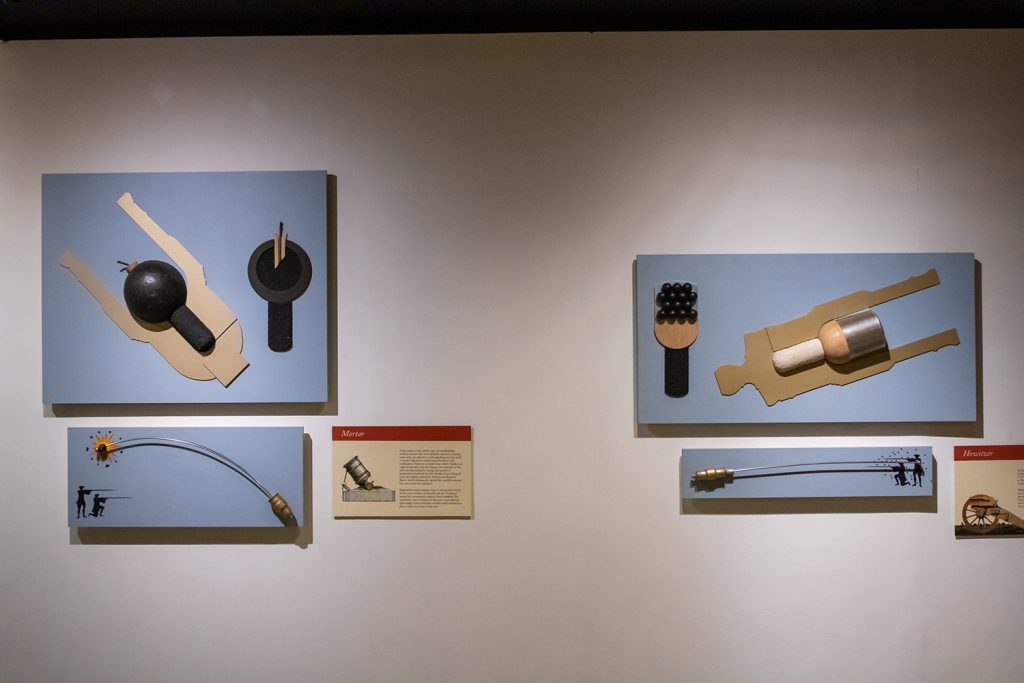

The British had three main types of artillery at their disposal: cannon, howitzers, and mortars. And if you have no idea what the differences are, no worries, because the Fort Pitt Museum has several great graphics explaining their differences and the pros and cons to each.

Above we have a diagram of a cannon. At the time cannon differentiated themselves by being relatively easier to construct and maintain. They fired solid, non-explosive projectiles at relatively flat trajectories. If you ever saw the Patriot with Mel Gibson, the scene where a gun fires a ball that then bounces through ranks of infantry and severs numerous legs, most likely that was a cannon.

The remaining two types were used for launching projectiles at higher angles, almost lobbing them up and over fortifications or enemy troop formations. Howitzers were the longer-ranged of the two and whilst broadly similar to cannon, at the time they differentiated themselves by being able to fire explosive projectiles. In other words, instead of a solid ball of iron as described above, this could explode and send shrapnel down on a larger area of massed infantry.

The mortar, in that sense, is similar to the howitzer. It could send explosive shells above troops and fortifications, but it was designed to do so at high-angles. This was particularly important in counter-siege warfare when the British defenders needed ways to fire at Native American soldiers who closely approached Fort Pitt’s defensive walls.

The graphics do a great job showing just how these three types of artillery were different and could be used to different effects. The graphics don’t do too much and don’t use elaborate illustrations. They are very effective and very efficient. Well done.

Credit for the pieces goes to the Fort Pitt Museum design staff.

Yesterday I discussed some of the work at the Fort Pitt Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Specifically we looked at Fort Duquesne, the French fortification that guarded the linchpin of their colonies along the Saint Lawrence Seaway and the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.

In 1753, the royal governor of Virginia dispatched a British colonial military officer, a lieutenant colonel, to demand the French withdraw from the chain of forts along the Allegheny River. The French politely refused. Undeterred, the lieutenant colonel, after returning the refusal, was sent with several dozen soldiers to push the British claim.

The lieutenant colonel discovered a French force south of present-day Pittsburgh. After largely surrounding the French force, the lieutenant colonel ordered his soldiers to open fire and in the ensuing battle the French force was destroyed by killing or capturing the vast majority of the force. That was the opening battle of the Seven Years War, a global conflict that stretched across North America, South America, Africa, India, and Asia.

The lieutenant colonel who started it all? George Washington.

At the war’s outset, Washington was involved—but did not lead—in another operation to oust the French from Fort Duquesne. This operation failed spectacularly with the death of its commander, Major General Edward Braddock. Three years later, British forces had sufficiently regrouped that they again attempted to take Fort Duquesne. After some tactical losses, the British continued to press the French. The French, seeing the vastly superior numbers of British soldiers, decided to withdraw and in blowing up their ammunition stores, destroyed Fort Duquesne.

The British, operationally commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Bouquet, a Swiss-born veteran British officer, occupied the smoldering ruins. There they proceeded to build an even larger fortification named after the British prime minister who ordered the site taken. The prime minister? William Pitt the Elder. The fort? Fort Pitt. The town that would develop around the fort? Pittsburgh.

When completed, Fort Pitt was the largest and most sophisticated British fortification west of the Appalachian Mountains. It guarded British colonial interests from both French and native forces who would have gladly retaken control of the area.

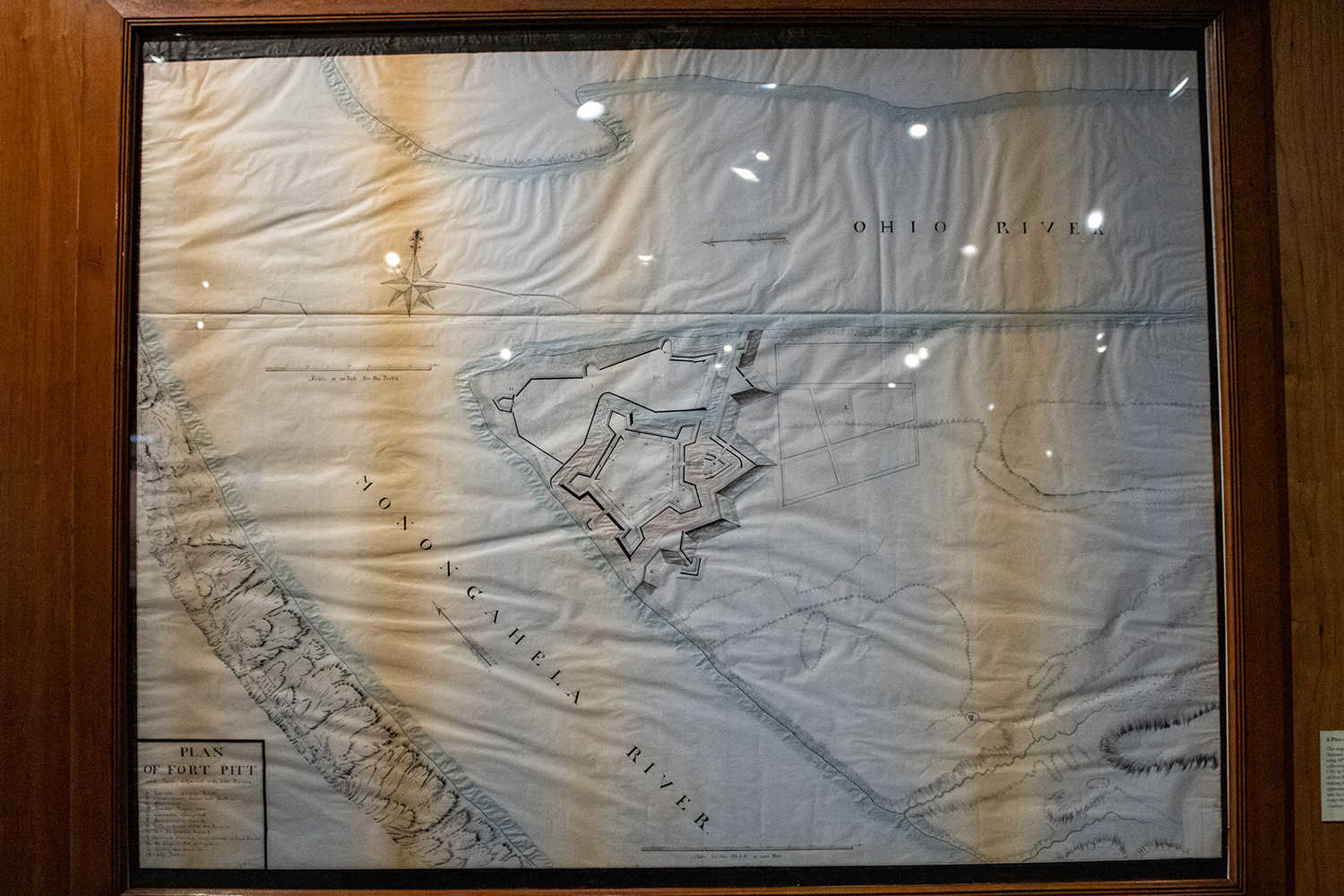

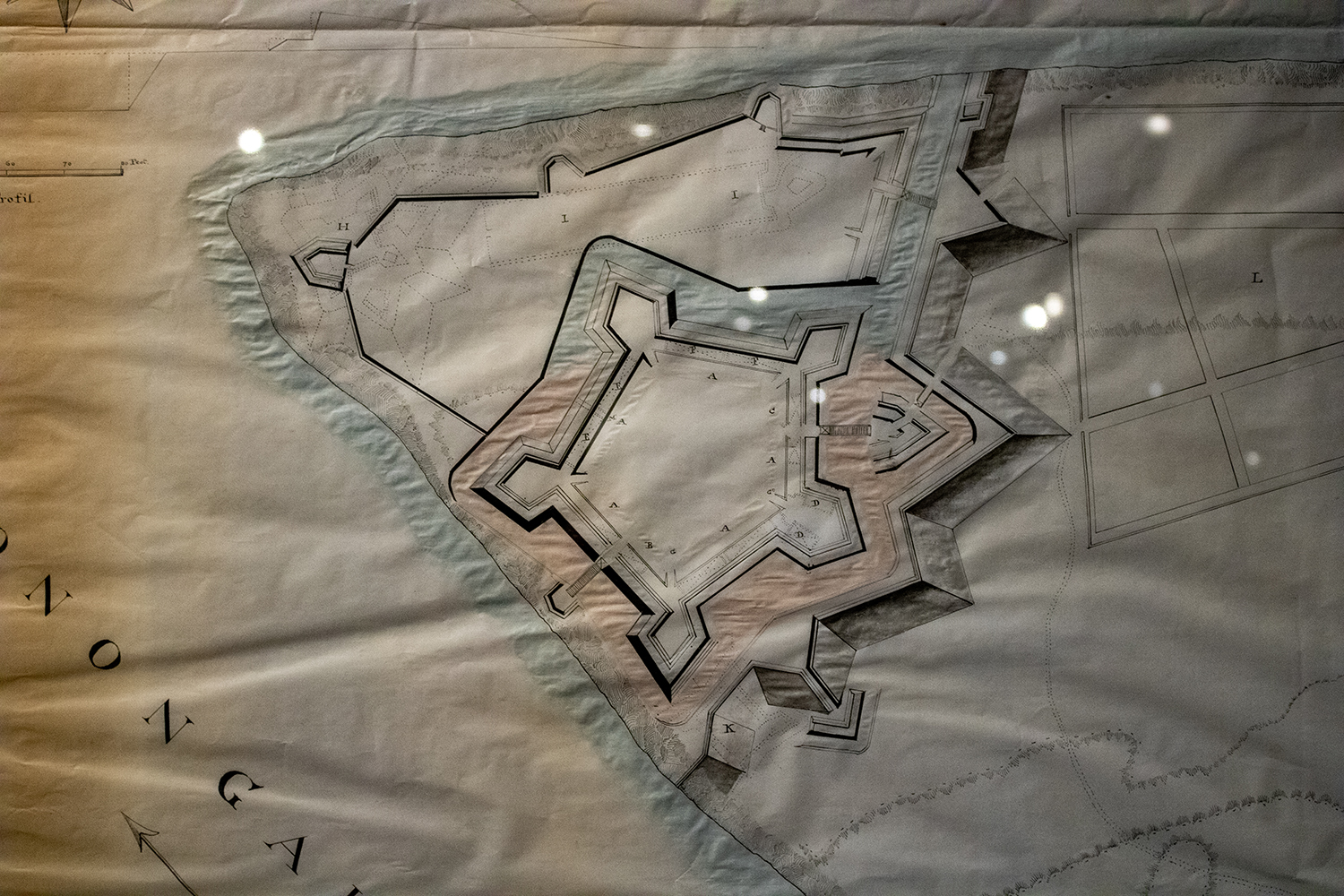

Today the Fort Pitt Museum has several diagrams and dioramas detailing what was at its completion. The photograph below is a reproduction of a diagram made in 1761 just prior to the fort’s completion of the fort and its immediate environs. Even the reproduction is itself a reproduction in that the creators used the same materials and methods as would have been used in the 18th century, lending it some of that aged quality.

And here we have a closer view of the fort itself. If you look closely to the left, nearer the forks of the Ohio, you can see the outline of the far smaller Fort Duquesne.

But for me the amazing part was walking into the museum where you are greeted with an amazing diorama of the Fort as it appeared in 1765. You can already see the emerging town of Pittsburgh outside the fortifications.

Credit for the original diagram goes to British military engineer Bernard Ratzer, its recreation was made by artists from the Carnegie Museum.

Credit for the diorama goes to Holiday Displays.

Pittsburgh exists because of the city sits at the confluence of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio Rivers. As far back as the early 18th century, English and French colonists had recognised the strategic value of the site and as imperial ambitions ramped up, the French finally wrested control of the area from the English and constructed a fort to defend the forks of the Ohio. They named it Fort Du Quesne (now Fort Duquesne) after Governor-General of New France, Marquis Du Quesne.

Fort Duquesne anchored a north-south chain of French forts linking the Ohio River to Lake Erie via the Allegheny River. Since the Allegheny drains into the Ohio and not Lake Erie, the French used a navigable tributary of the Allegheny, the imaginatively named French Creek, to reach just a few miles from the fort on Lake Erie, Fort Presque Isle, from which they portaged overland to Fort Le Bœuf. From there they travelled down the river or overland via the Venango Path to Fort Machault situated at the confluence of French Creek and the Allegheny River.

This chain of forts and the control they established over the Ohio allowed the French to link their colony of New France in present day Québec along the Saint Lawrence River to their colonies along the Mississippi in the Illinois Country via Lake Erie then the Allegheny and Ohio Rivers, which feed into the Mississippi River. The Mississippi of course then empties into the Gulf of Mexico through the then French colony of Louisiana and New Orleans. Strategically this allowed the French to surround and choke the British colonies along the eastern seaboard from territory and resources west of the Appalachian Mountains.

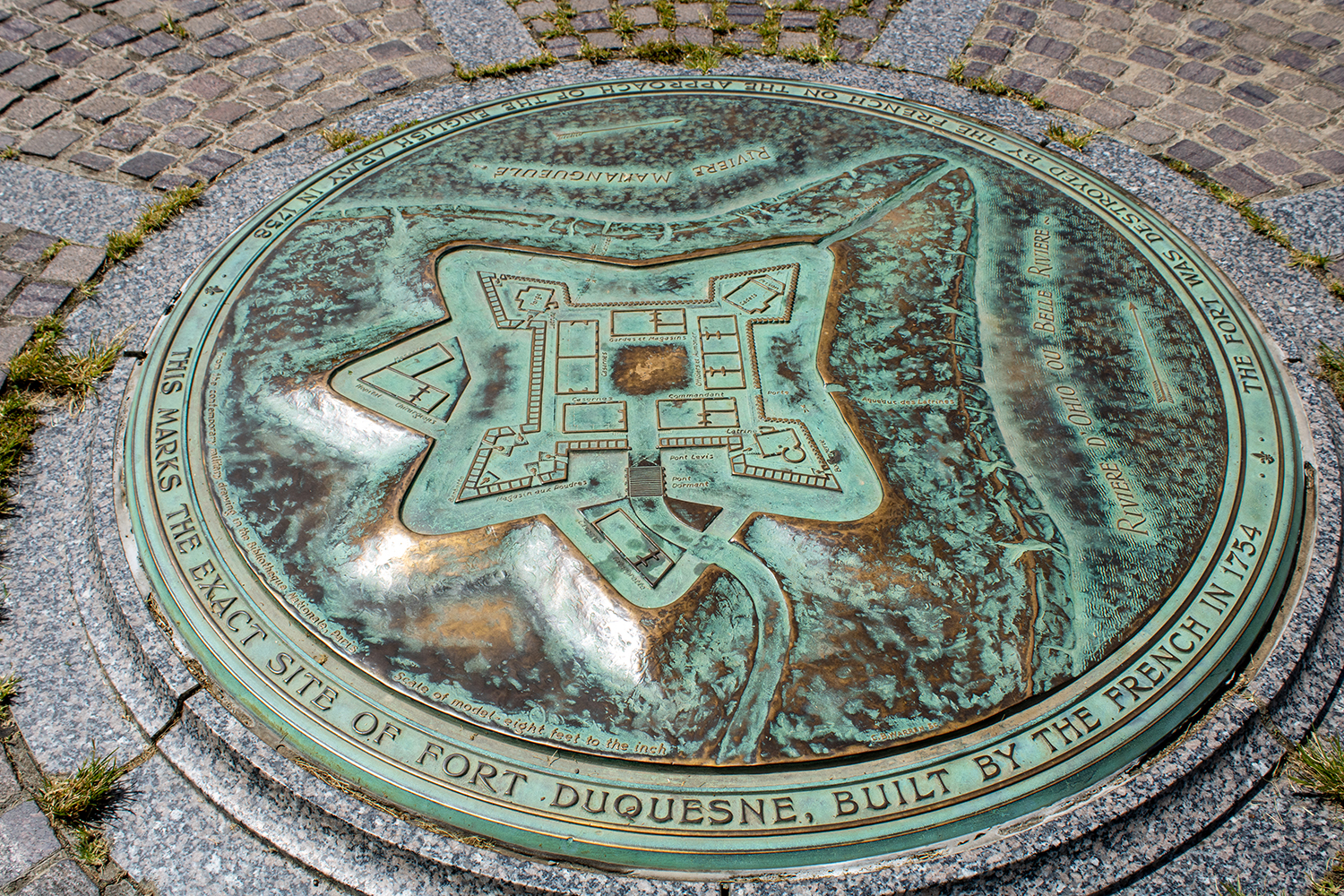

At the site of Fort Duquesne on what is now called Point State Park, a granite stone outline of the original French fort sits in a grass field. And at the centre of the outline is a plaque diagramming the fort’s design.

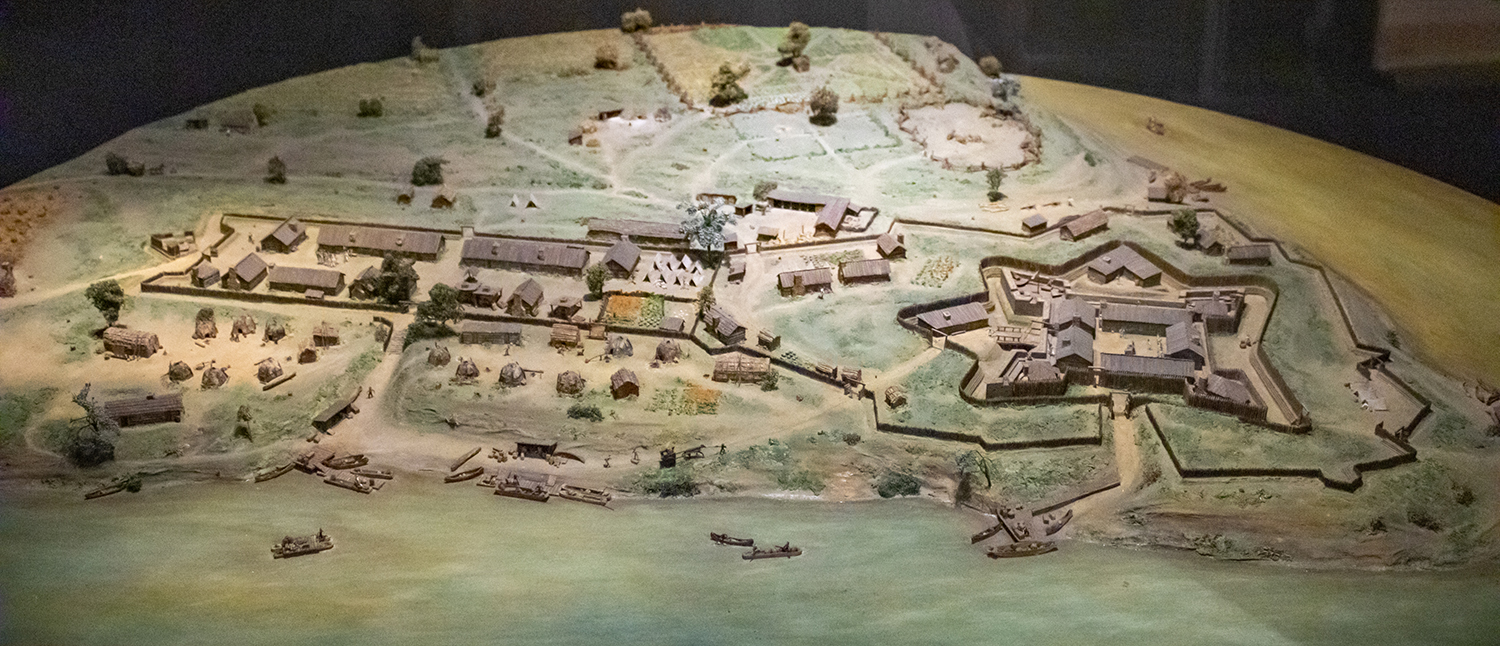

Thankfully for history lovers, the park also contains a history museum dedicated to Fort Pitt, the larger British successor fortification to Fort Duquesne. But inside, the history of Fort Pitt would be incomplete without a discussion of Fort Duquesne and that includes a nice diorama. You will note more details here, however, as the initial fort seen in the above diagram was expanded to include more area for barracks, farms, and ancillary activities like forges.

But even still a closer shot of the fort itself shows what the physical buildings would have looked like above and beyond a two-dimensional diagram.

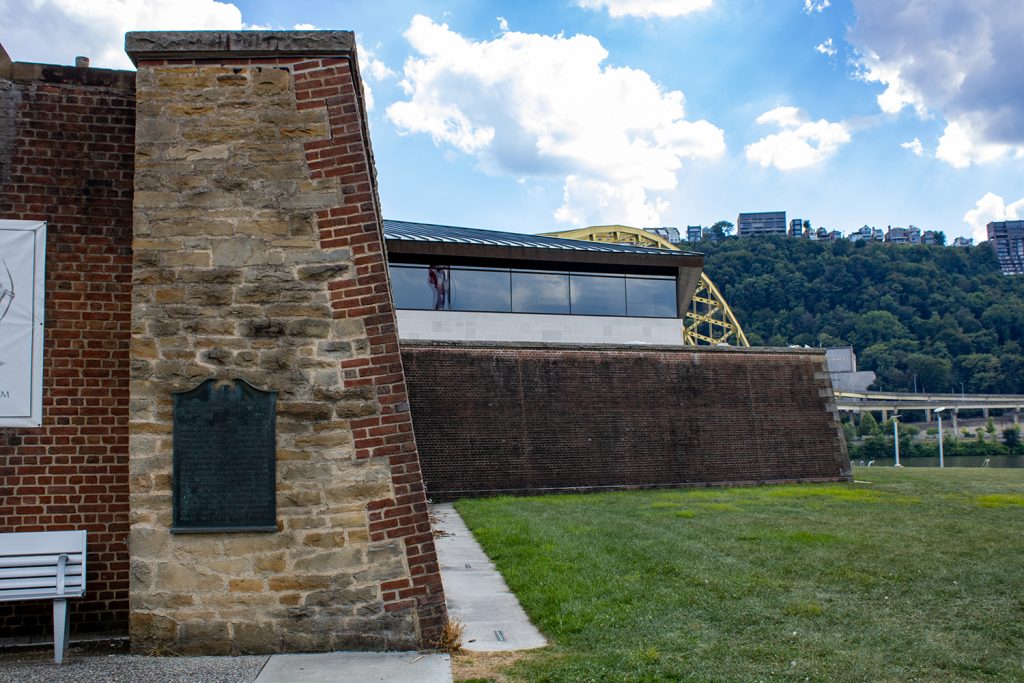

Having been to the site, however, you can see that Fort Duquesne and the later Fort Pitt weren’t necessarily as defensible as one may think. Just to the south across the Monongahela River is a ridgeline that offers clear lines of fire into the forts. Some well positioned artillery would have made holding the forts tenuous at best. Of course hauling artillery and ammunition up to the ridge’s summit is easier said than done. Here’s a photo from the Fort Pitt Museum, whose exterior walls reconstruct one of the later Fort Pitt’s bastion walls. You can see in the background the ridge line of Mount Washington (originally named Coal Hill) stands far above the fort’s defences. Artillery could easily angle down and fire into the forts, be them either Duquesne or Pitt.

Credit for the marker goes to I assume the designers at the Pennsylvania State Park commission.

Credit for the dioramas goes to Holiday Displays, who created the originals in the 1960s.

I spent the last two weeks out of town, and my post for the Friday before didn’t happen because there was a fire at my building—I and my unit are fine—that knocked out internet for about 24 hours. But now I have returned.

One of the things I did was visit the city of Pittsburgh in western Pennsylvania. There I discovered the city has a World War II era submarine, the USS Reqin, a Tench-class submarine that launched at the end of the war and saw no active combat. She was later preserved and arrived at the Carnegie Science Centre in Pittsburgh where she serves as a museum ship.

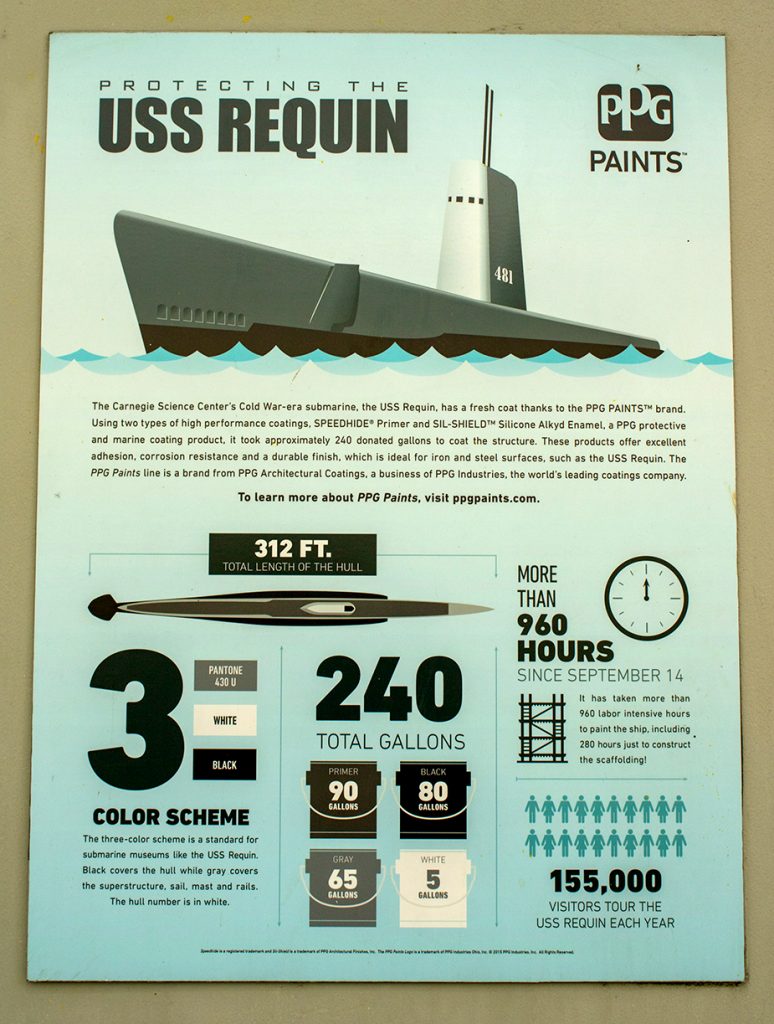

As I waited for the self-guided tour to begin, I spotted a small poster with some big numbers. Naturally I investigated and found it to be a marketing piece by PPG, a Pittsburgh-based paint and coatings company. The poster detailed the work that went in the preservation of the submarine’s exterior using PPG’s own paints and coatings.

We can see the large numbers clearly and to the piece’s credit the hierarchy works. What are we talking about? Three paints applied to the submarine in these quantities in this amount of time. The only factette not totally relevant is how many tourists annually visit the submarine.

Design wise, the poster does a nice job of dividing up its space into an attention-grabbing upper-half. After all, it grabbed my attention. The lower half then subdivides into three columns that speak to the aforementioned subjects. The last column then divides again into halves.

As marketing design does, it’s not the most offensive. For example, we don’t have the gallon buckets sized or scaled differently. The designers used a restrained palette and kept a consistent typographic treatment.

Admittedly, I was a bit disappointed because I had thought it would be some facts or data about the submarine itself. But for what the piece is, I thought it did a nice job.

Credit for the piece goes to PPG’s graphics department.

I had something else for today, but this morning I opened the door and found my morning paper. Nothing terribly special. No massive headline. No large front-page graphic. See what I mean?

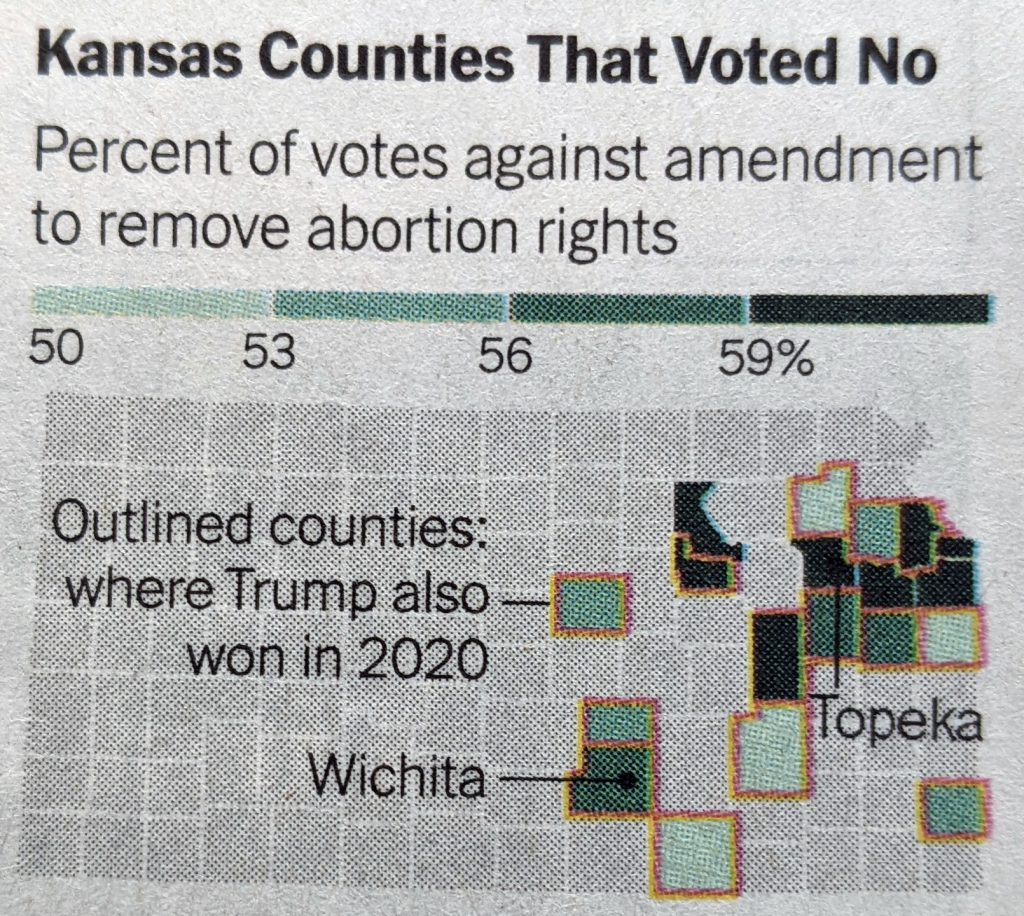

But then as I bent down to pick it up, I spotted a little tree map. But it turned out it wasn’t a tree map. It was a rectangle, largely, but it was actually a county map of Kansas. It was so small it fit within a single column.

The map showed those counties that had a majority vote in favour of keeping abortion rights. And then those counties that also voted for Trump in 2020 were outlined in orange—a good colour pairing. Turned out a number of counties did.

Without wading into the politics of it, because that’s a separate article, this was a great little map. It didn’t need to be crazy complicated or even large.

Credit for the piece goes to the New York Times graphics department.

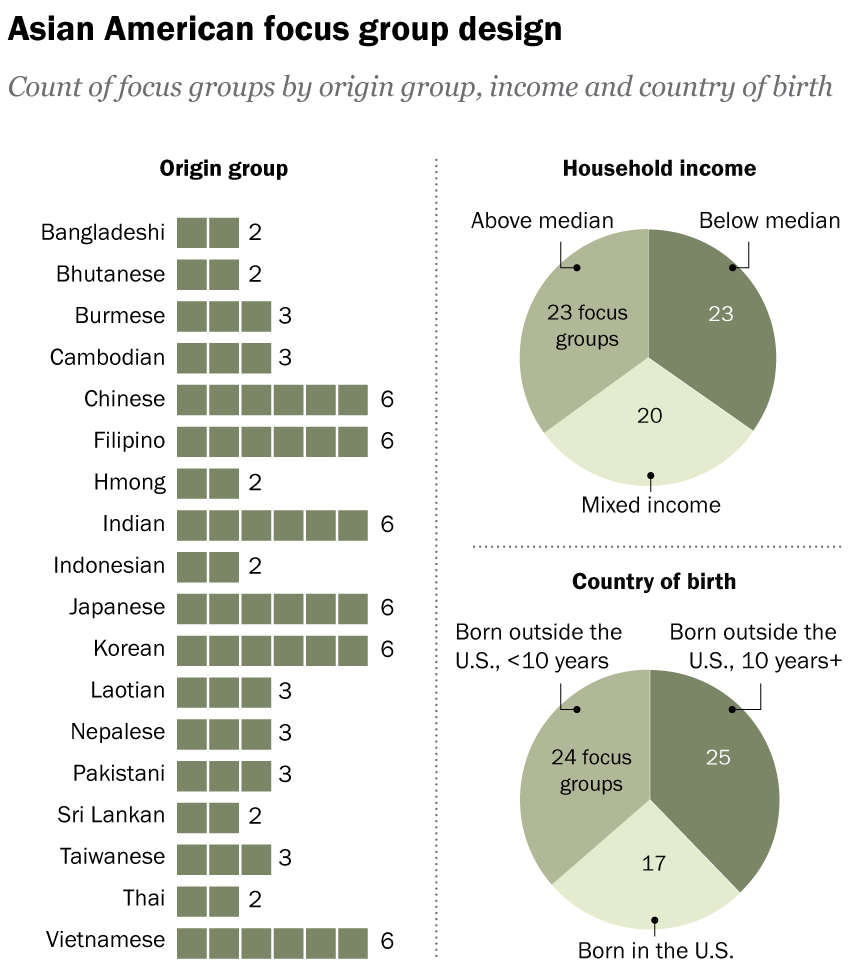

Pew recently released a report into the Asian American experience. The report used 66 different focus groups to gather feedback and then summarised that with quotes, video bits, and lots of text. But at the beginning of the report was a nice little graphic that detailed the composition of the focus groups.

This is not a fancy graphic, nor need it be given its supplemental role to the overall piece. But I think it does a reasonable job of showing the construction of the overall focus group demographics, a key point to understanding the responses.

On the left we have a simple count of the number of focus groups by origin. For Indonesians we see there were two focus groups. And thus we have a number two besides the two blocks. Here the two is entirely extraneous and serves as a distracting visual sparkle at the end of the blocks. The advantage of using blocks as opposed to say a bar is that you can visualise the individual components or units, in this case there were two distinct focus groups of Indonesian origin. A user reading this chart should be able to count two blocks. And if they cannot count two blocks, I suspect they would be unable to grasp what the “2” means let alone the rest of the report.

To the right we have two pie charts. My…reticence…to use pies is well-known to long-time readers of Coffeespoons. But here we have the same type of data, counts of focus groups, and I have to wonder: why the designers did not stick with the same model of using individual blocks?

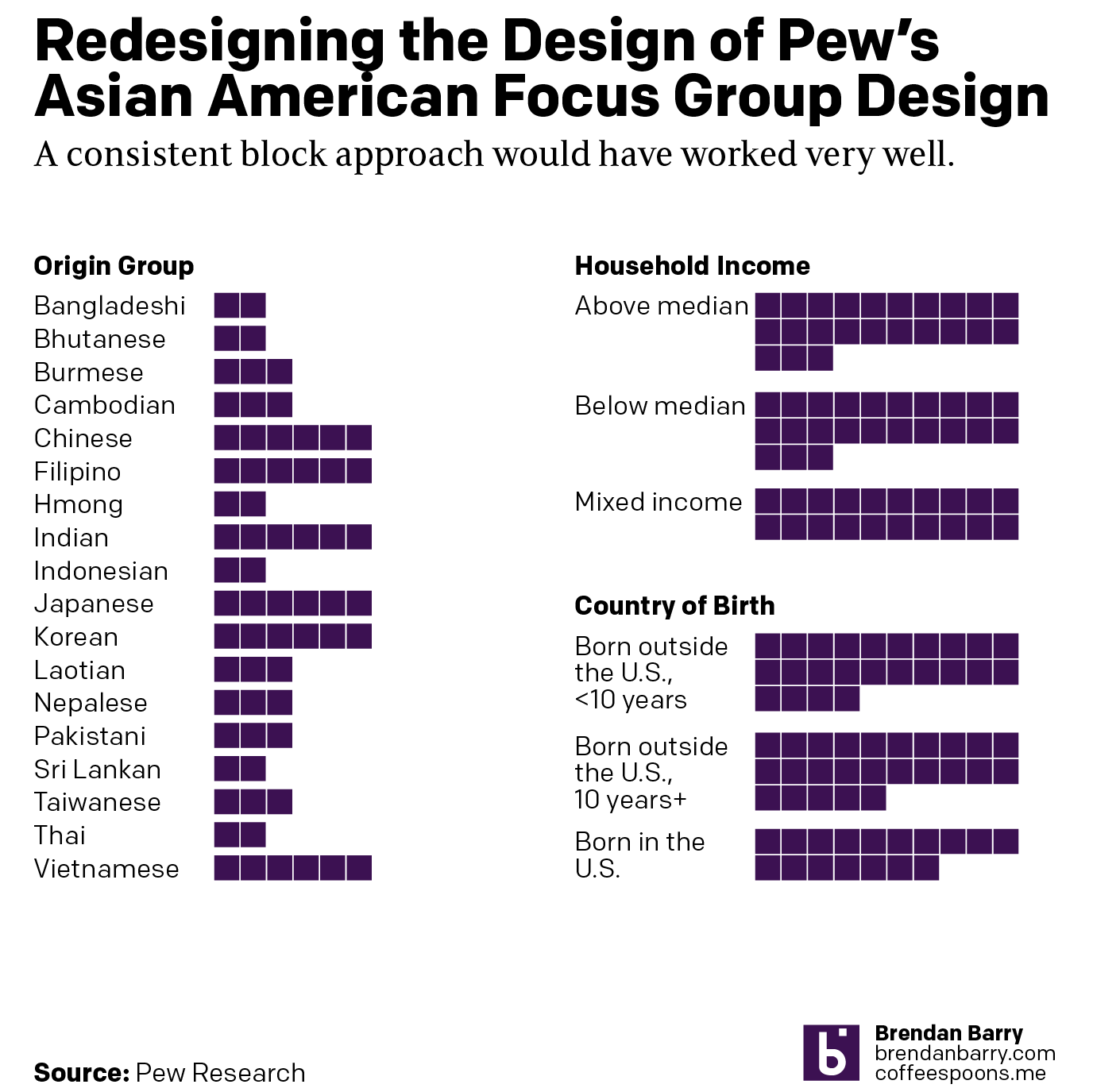

Here I chose to redesign the pie charts.

Nothing here is really new, I just removed the labels because people can count if they need to know the exact number. The labels add visual clutter to the design. And then of course I removed the pie charts and replaced them with blocks like on the left. I was even able to keep the layout roughly the same, albeit within my own graphics template.

Credit for the original goes to the Pew graphics department.

Credit for the redesign is mine.

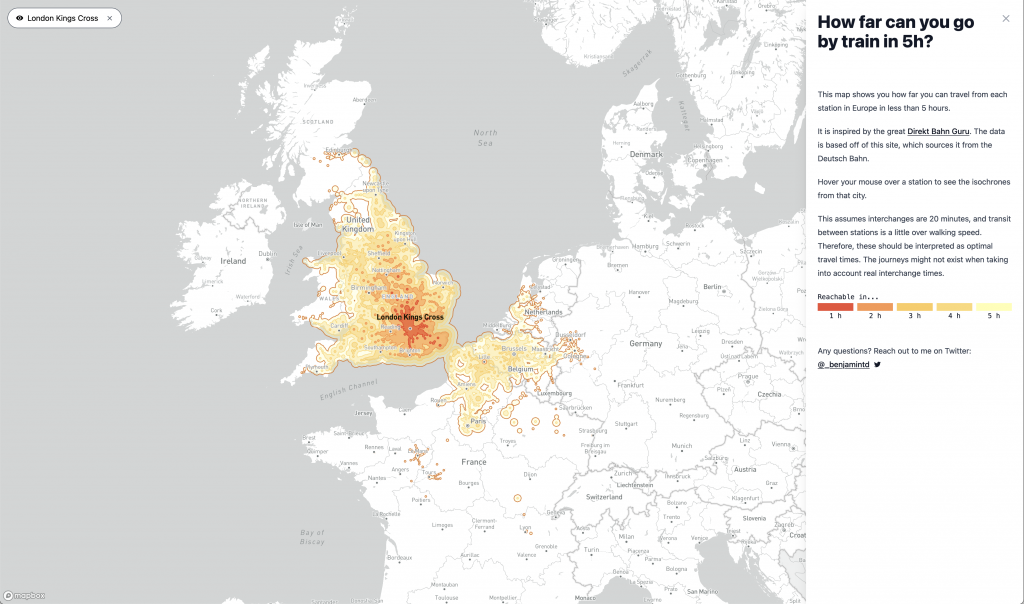

Many of us have pent up travel demand. Covid-19 remains with us, lingering in the background, but it’s largely from our front-of-mind. For those of my readers in Europe, or just curious how superior European rail infrastructure is over American, this piece from Benjamin Td provides some useful information.

It uses isochrones to map out how much a traveller could travel if he would travel five hours. For this screenshot I chose London’s King’s Cross station. In red we see distances within a one-hour rail ride from said station. In the lightest yellow are those places within the five-hour distance.

The interactive map allows users to investigate stations throughout Europe. Mousing over various parts brings up different stations. Clicking on the station freezes the station on the map allowing the user to zoom in or out and investigate different areas of Europe.

Colour-wise, things work well. The desaturated map allows the yellow-to-red palette to shine. And to the right a closable legend, which unfortunately cannot be reopened once closed for the only real blemish on the piece. Even typographically, the labels appear in grey whereas selected stations appear in black.

A well done piece.

Credit for the piece goes to Benjamin Td.

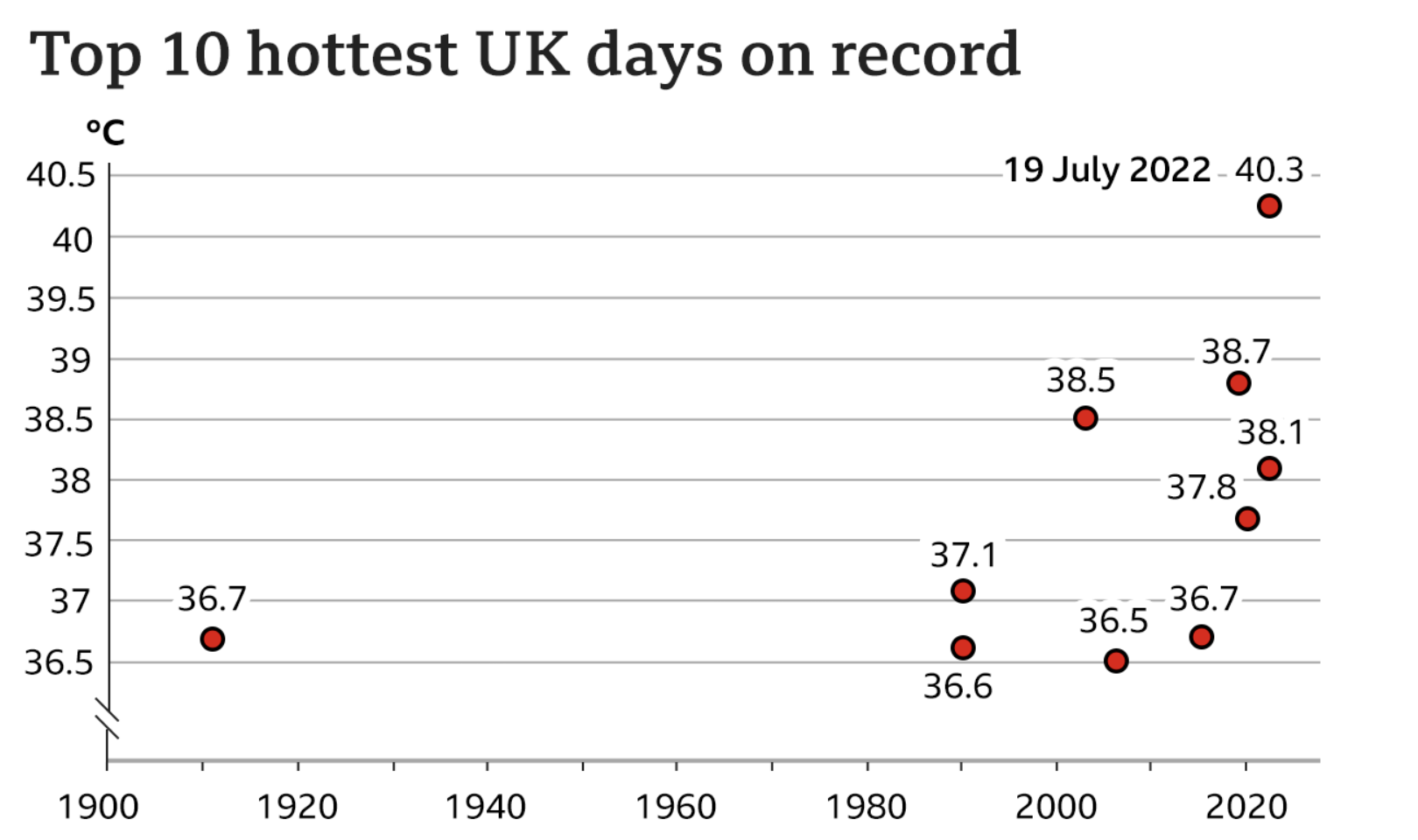

Recently the United Kingdom baked in a significant heatwave. With climate change being a real thing, an extreme heat event in the summer is not terribly surprising. Also not surprisingly, the BBC posted an article about the impact of climate change.

The article itself was not about the heatwave, but rather the increasing rate of sea level rise in response to climate change. But about halfway down the article the author included this graphic.

As graphics go, it is not particularly fancy—a dot plot with ten points labelled. But what this piece does well is using a dot plot instead of the more common bar chart. I most typically see two types of charts when plotting “hottest days” or something similar. The first is usually a simple timeline with a dot or tick indicating when the event occurred. Second, I will sometimes see a bar chart with the hottest days presented all as bars, usually not in the proper time sequence, i.e. clustered bar next to bar next to bar.

My issue with the the latter is always where is the designer placing the bottom of the bar? When we look at the best temperature graphics, we usually refer to box plots wherein the bar is aligned to the day and then top of the bar is the daily high and the bottom of the bar the daily low. It does not make sense to plot temperatures starting at, say 0º.

In this particular case, however, the dates would appear to overlap too closely to allow a proper box plot. Though I suspect—and would be curious to see—if the daily minimum temperatures on each of those ten hottest days have also increased in temperature.

As to the timeline option, this does a better job of showing not just the increasing frequency of the hottest days, but also the rising maximum value. In the early 20th century the hottest day was 36.7ºC, and you can see a definite trend towards the hottest days nearing and finally surpassing 40ºC.

I do wonder if a benchmark line could have been added to the chart, e.g. the summertime average daily high or something similar. Or perhaps a line showing each day’s temperature faintly in the background.

Finally, I want to point out the labelling. Here the designers do a nice job of adding a white stroke or outline to the outside of the text labels. This allows the text to sit atop the y-axis lines and not have the lines interfere with the text’s legibility. That’s always a nice feature to see.

Credit for the piece goes to the BBC graphics department.

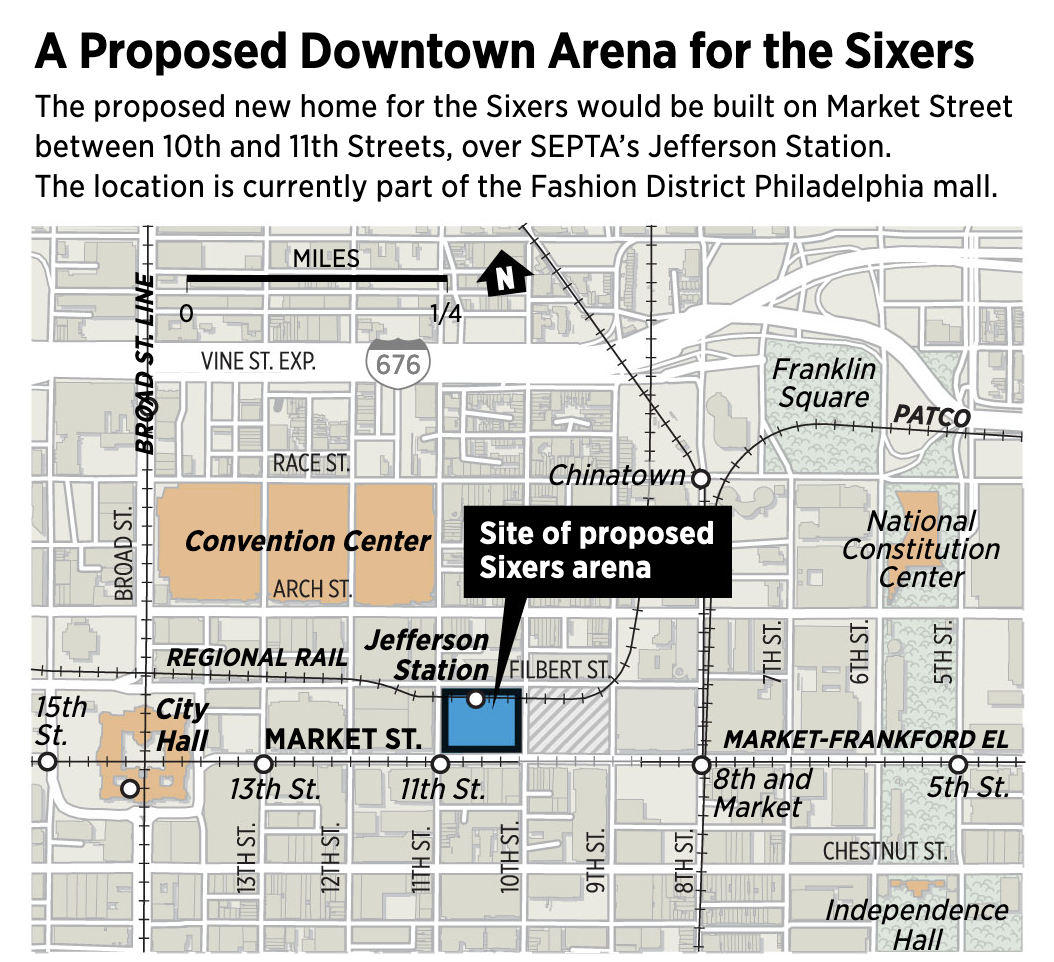

I woke up this morning and the breaking news was that the local basketball team, the 76ers, proposed a new downtown arena just four blocks from my office. The article included a graphic showing the precise location of the site.

For our purposes this is just a little locator map in a larger article. But I wanted to draw attention to two things in an otherwise nice map. First, if you look carefully on the left you can see the label for the Broad Street Line placed over the actual railway line, which is what makes it so difficult to read. I probably would have shifted the label to the left to increase its legibility.

Second, and this is a common for maps of Philadelphia, is the actual north-south route of said Broad Street Line, one of the three subway lines running in the city. (You all know of the Broad Street and Market–Frankford Elevated, but don’t forget the PATCO.) If you look closely enough it appears to run directly underneath Broad Street in a straight line. But where it passes beneath City Hall you will see the little white dot locating the station is placed to the left of the railway line.

Why is that?

Well when it was built, Philadelphia’s City Hall was the tallest habitable building in the world. Whilst clearly supplanted in that record, the building remains the largest free-standing masonry building in the world. But that means it has deep and enormous foundations. Foundations that could not be disturbed when the city was running a subway line directly beneath Broad Street.

Consequently, the Broad Street Line is not actually straight—ride it heading south into City Hall Station and you’ll notice the sharp turn both in its bend and the loud screeching of metal. The line bends around parts of the building’s foundations, sharply on the north side and more gently on the south side. So the actual station is still beneath City Hall, but offset to the west.

But most of the time it’s easier just to depict the route as a straight line running directly beneath City Hall.

Credit for the piece goes to John Duchneskie.