Sunday night, news broke that a number of European football clubs were creating a rogue league, the European Super League. My British and European readers—and Americans who follow football—will know the names of Manchester United, Liverpool, AC Milan, Juventus, Real Madrid, and the others.

To put this in perspective for my American readers, imagine the Yankees, Dodgers, Red Sox, Astros, Padres, Mets, Cardinals, Phillies, Angels, and Nationals saying that they were leaving Major League Baseball to go and form their own new baseball league. That they were doing so to “save the sport”. But in so doing, they also guarantee they all make the playoffs every year.

My frequent readers and those who know me will know I’m a fan of the Boston Red Sox. I should point out that the owner of the Red Sox, John Henry, owns both the Red Sox and Liverpool through his company Fenway Sports Group.

Of course, the analogy doesn’t quite hold up, because there are some significant differences between American sports and European football. Relegation is a big one. Personally, I wish American sports had some way of using relegation to incentivise teams to not intentionally suck.

The basic premise of relegation. Take English football. You have four levels of play and in theory any team can exist in any level. Each year, the worst teams move from their current level down one whilst the best teams move up. And for the top level, the top teams get to compete in lucrative European-wide matches. That is a bit simplistic, but imagine that at the end of last year, the Pirates, Rangers, Tigers, and Red Sox became AAA minor league teams and the four best AAA minor league teams became MLB teams. MLB teams would theoretically try to do everything they could to stay in the MLB and not drop to AAA, because that would mean a loss of money. After all, the Yankees would no longer be heading to Fenway nor the White Sox to Detroit. Would seeing the Detroit Tigers play the Woo Sox really be worth the ticket prices you pay at Comerica Park?

But that’s not how American sports work. And so a few American owners, namely those of Manchester United, Arsenal, and Liverpool, want to ensure a steady stream of money. By creating their own league where their teams cannot be relegated, they guarantee that revenue stream.

In other words, this is all about the owners of these Super League teams making even more money.

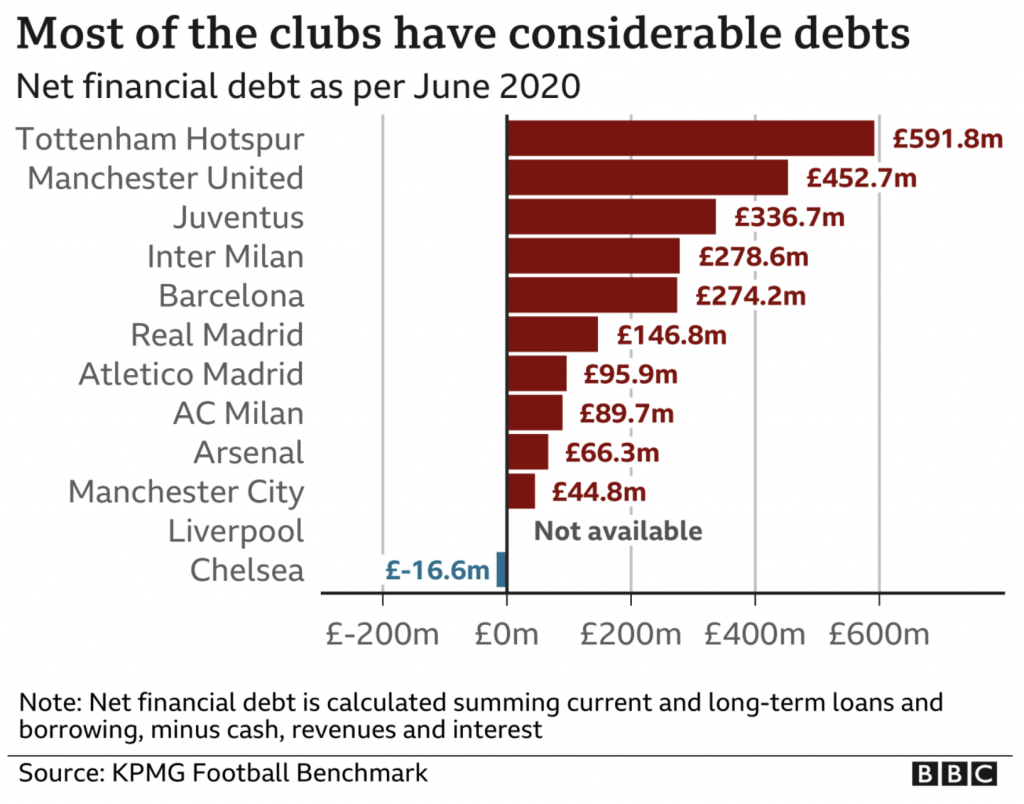

Because, during the last year, teams have been hurting without fans in attendance. And that gets us to why I can write this up. Because the BBC in an article about this new league addressed the fact that most of these teams are heavily in debt.

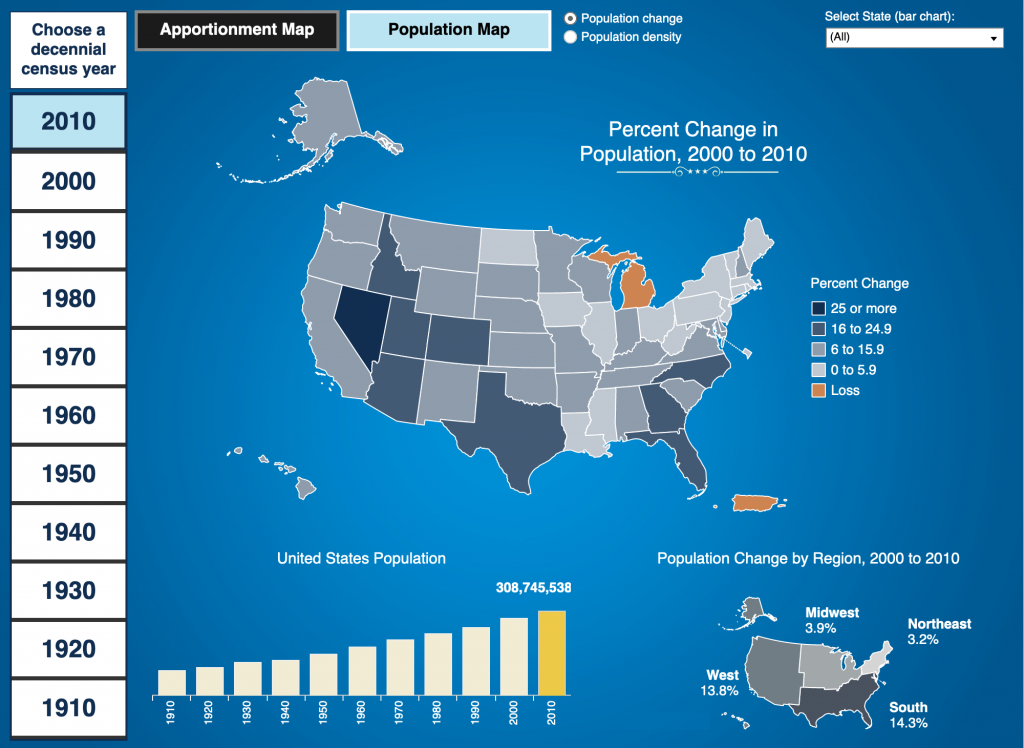

This graphic, however, is a bit misleading. Look at Liverpool. There is no available data for how much financial debt the club holds. So why is it placed between Chelsea and Manchester City? It could well have more debt than Tottenham. Liverpool should really be left off this chart and included in the note, because its placement suggests that it has little debt, when that may well not be the case. This is a really misleading graphic when it comes to how Liverpool fits with the other 11 clubs.

From a design standpoint, I’m also not clear on why the x-axis line extends beyond the labels for £-200m and £600m.

I’m not going to touch all the data labels. That’s for another piece I’ve been working on off and on for a little while now.

At this point I should point out that I was going to post this article later, but in the last 18 hours or so the whole thing has fallen apart as the English teams, followed by the others, have been dropping out under immense pressure from the sport and their fans. To bring back my analogy above, imagine MLB retaliating and saying that if those teams created their own league, the players would not be allowed to play in any other matches and the teams would be locked out from all other competitive baseball games. It’s a mess.

Credit for the piece goes to the BBC graphics department.