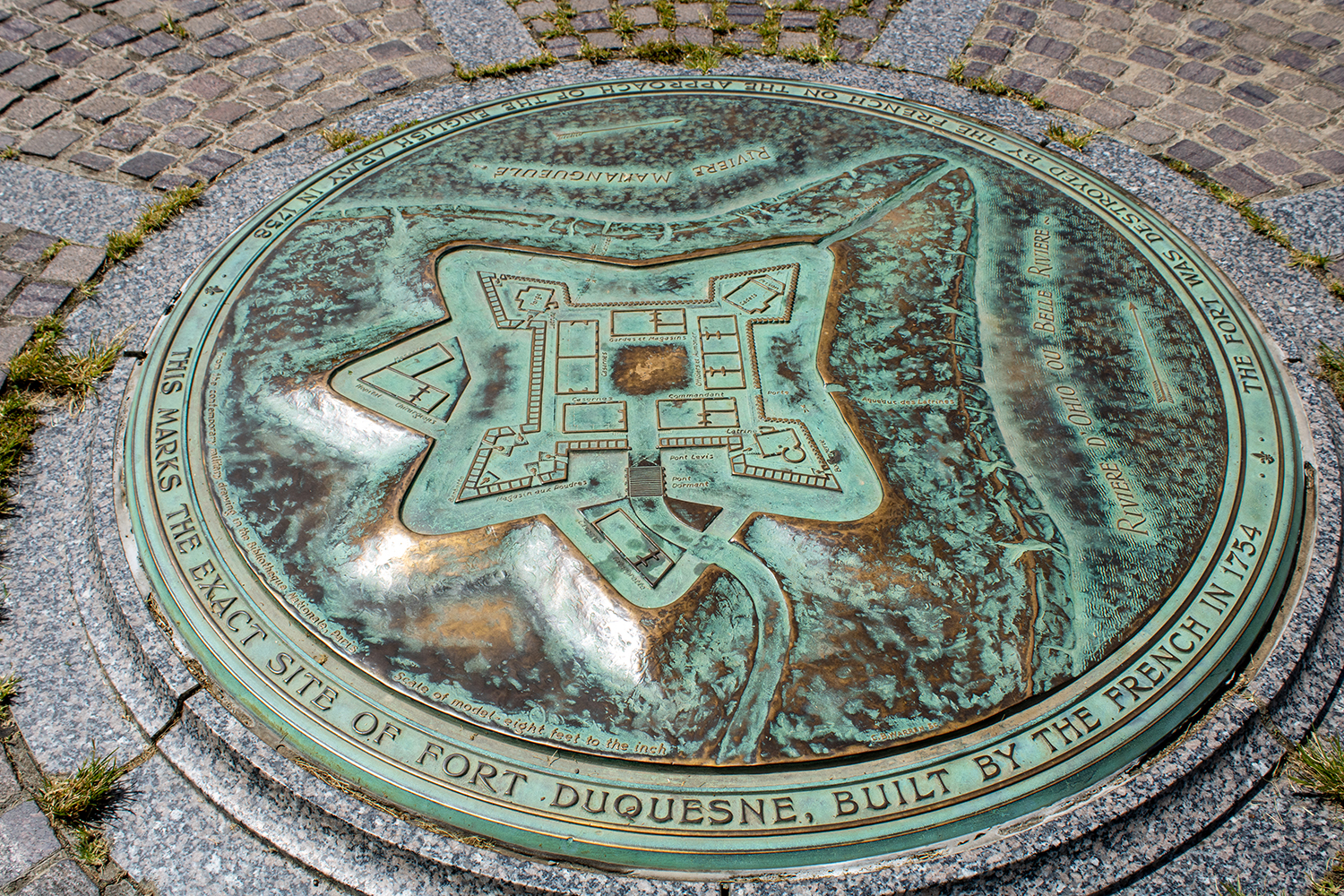

Yesterday I discussed some of the work at the Fort Pitt Museum in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Specifically we looked at Fort Duquesne, the French fortification that guarded the linchpin of their colonies along the Saint Lawrence Seaway and the Mississippi and Ohio River valleys.

In 1753, the royal governor of Virginia dispatched a British colonial military officer, a lieutenant colonel, to demand the French withdraw from the chain of forts along the Allegheny River. The French politely refused. Undeterred, the lieutenant colonel, after returning the refusal, was sent with several dozen soldiers to push the British claim.

The lieutenant colonel discovered a French force south of present-day Pittsburgh. After largely surrounding the French force, the lieutenant colonel ordered his soldiers to open fire and in the ensuing battle the French force was destroyed by killing or capturing the vast majority of the force. That was the opening battle of the Seven Years War, a global conflict that stretched across North America, South America, Africa, India, and Asia.

The lieutenant colonel who started it all? George Washington.

At the war’s outset, Washington was involved—but did not lead—in another operation to oust the French from Fort Duquesne. This operation failed spectacularly with the death of its commander, Major General Edward Braddock. Three years later, British forces had sufficiently regrouped that they again attempted to take Fort Duquesne. After some tactical losses, the British continued to press the French. The French, seeing the vastly superior numbers of British soldiers, decided to withdraw and in blowing up their ammunition stores, destroyed Fort Duquesne.

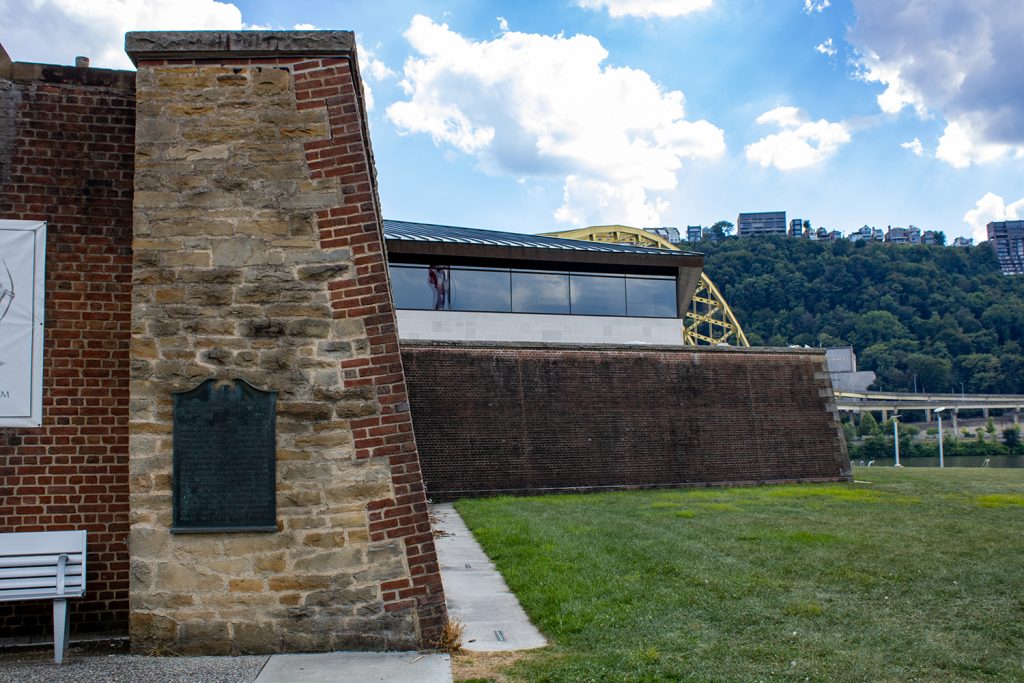

The British, operationally commanded by Lieutenant Colonel Henry Bouquet, a Swiss-born veteran British officer, occupied the smoldering ruins. There they proceeded to build an even larger fortification named after the British prime minister who ordered the site taken. The prime minister? William Pitt the Elder. The fort? Fort Pitt. The town that would develop around the fort? Pittsburgh.

When completed, Fort Pitt was the largest and most sophisticated British fortification west of the Appalachian Mountains. It guarded British colonial interests from both French and native forces who would have gladly retaken control of the area.

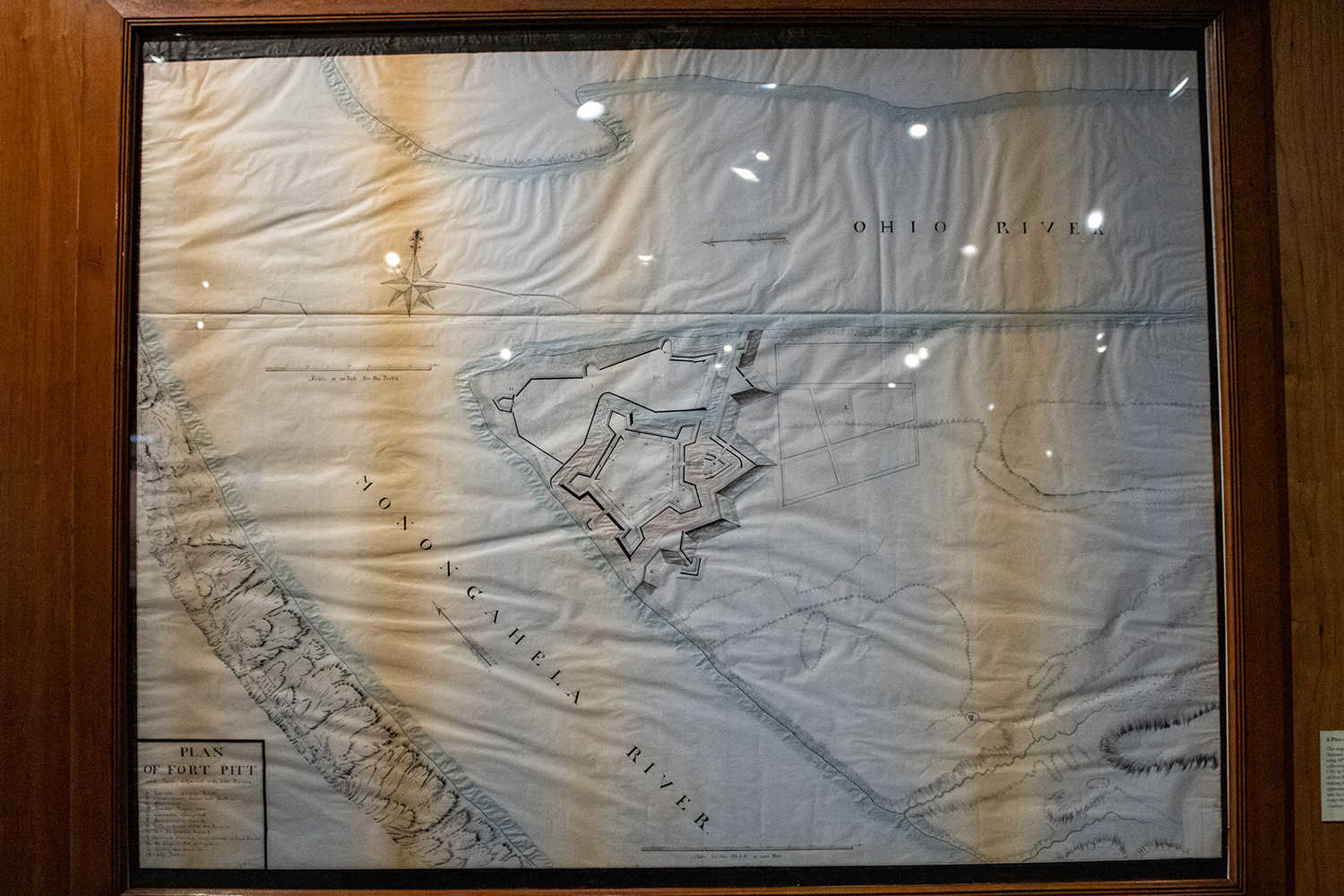

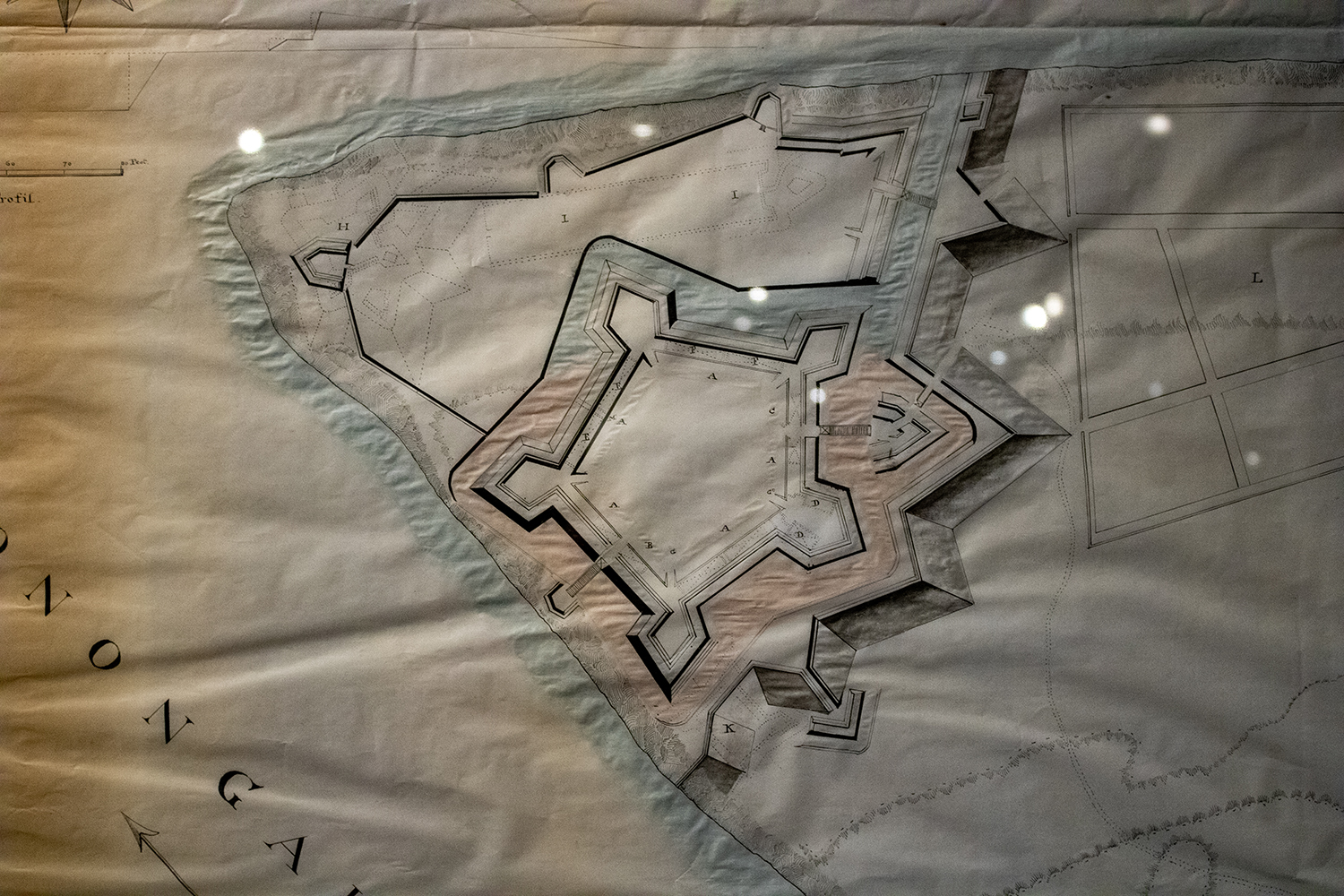

Today the Fort Pitt Museum has several diagrams and dioramas detailing what was at its completion. The photograph below is a reproduction of a diagram made in 1761 just prior to the fort’s completion of the fort and its immediate environs. Even the reproduction is itself a reproduction in that the creators used the same materials and methods as would have been used in the 18th century, lending it some of that aged quality.

And here we have a closer view of the fort itself. If you look closely to the left, nearer the forks of the Ohio, you can see the outline of the far smaller Fort Duquesne.

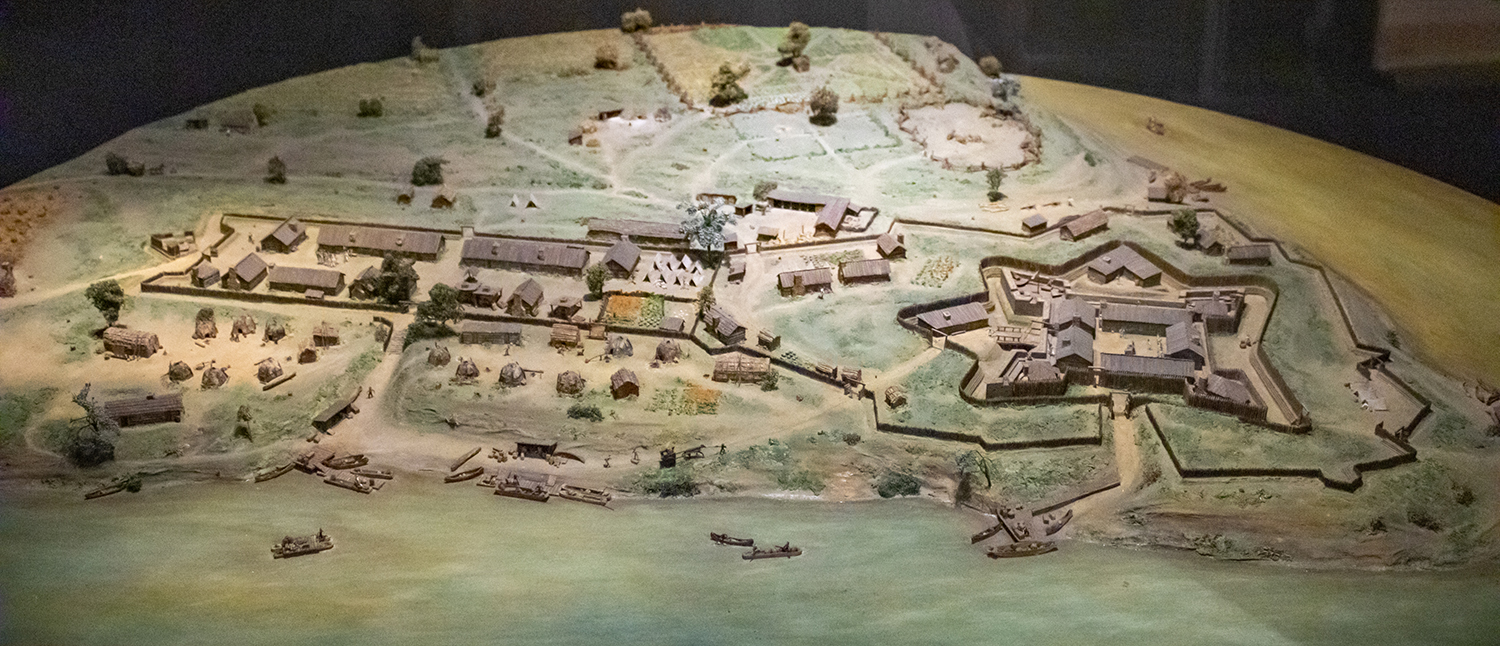

But for me the amazing part was walking into the museum where you are greeted with an amazing diorama of the Fort as it appeared in 1765. You can already see the emerging town of Pittsburgh outside the fortifications.

Credit for the original diagram goes to British military engineer Bernard Ratzer, its recreation was made by artists from the Carnegie Museum.

Credit for the diorama goes to Holiday Displays.