In case you weren’t aware, the US election is in less than a week, five days. I had written a long list of issues on the ballot, but it kept getting longer and longer so I cut it. Suffice it to say, Americans are voting on a lot of issues this year. But a US presidential election is not like many other countries’ elections in that we use the Electoral College.

For my non-American readers, the Electoral College, very briefly, was created by the country’s founding fathers (Washington, Jefferson, Adams, Franklin, et al.) to do two things. One, restrict selection of the American president to a class of individuals who theoretically had a broader/deeper understanding of the issues—but who also had vested interests in the outcome. The founders did not intend for the American people to elect the president. The second feature of the Electoral College was to prevent the largest states from dominating smaller states in elections. Why else would Delaware and Rhode Island surrender their sovereignty to join the new United States if Virginia, Pennsylvania, and New York make all the decisions? (The founders went a step further and added the infamous 3/5 clause, but that’s another post.)

So Americans don’t elect the president directly and larger states like California, New York, and Texas, have slightly less impact than smaller states like Wyoming, Vermont, and Delaware. Each state is allotted a number of Electoral College votes and the key is to reach 270. (Maybe another time I’ll get into the details of what happens in a 269–269 tie.) Many Americans are probably familiar with sites like 270 To Win, where you can determine the outcome of the election by saying who won each state. But, even though the US election is really 50 different state elections, common threads and themes run through all those states and if one candidate or another wins one state, it makes winning or losing other states more or less likely. FiveThirtyEight released a piece that attempts to link those probabilities and help reveal how decisions voters in one state make may reflect on how other voters decide.

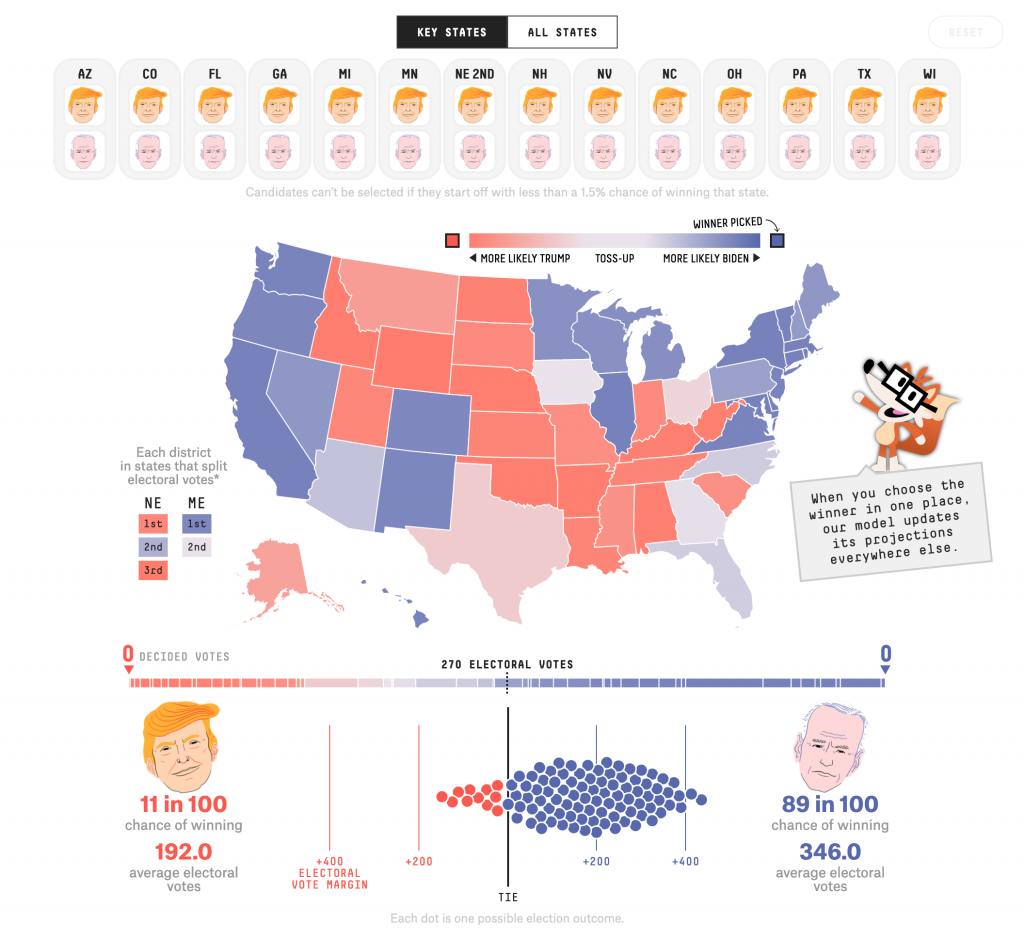

The interface is fairly straightforward—I’m looking at this on a desktop, though it does work on mobile—with a bunch of choices at the top and a choropleth map below. There we have a continually divergent gradient, meaning the states aren’t grouped into like bins but we have incredibly subtle differences between similar states. (I should also point out that Maine and Nebraska are the two exceptions to my above description of the Electoral College. They divide their votes by congressional district, whoever wins the district gets that Electoral College vote and then the state overall winner receives the remaining two votes.)

Below that we have a bar chart, showing each state, its more/less likely winner state and the 270 threshold. Below that, we have what I’ve read/heard described as a ball plot. It represents runs of the simulation. As of Thursday morning, the current FiveThirtyEight model says Trump has an 11 in 100 chance of winning, Biden, conversely, an 89-in-100 chance.

But what happens when we start determining the winners of states?

Well, for my non-American readers, this election will feature a large number of voters casting their ballots early. (I voted early by mail, and dropped my ballot off at the county election office.) That’s not normal. And I cannot emphasise this next point enough. We may not know who wins the election Tuesday night or by the time Americans wake up on Wednesday. (Assuming they’re not like me and up until Alaska and Hawaii close their polls. Pro-tip, there’s a potentially competitive Senate race in Alaska, though it’s definitely leaning Republican.)

But, some states vote early and/or by mail every year and have built the infrastructure to count those votes, or the vast majority of them, on or even before Election Day. Three battleground states are in that group: Arizona, Florida, and North Carolina. We could well know the result in those states by midnight on Election Day—though Florida is probably going to Florida.

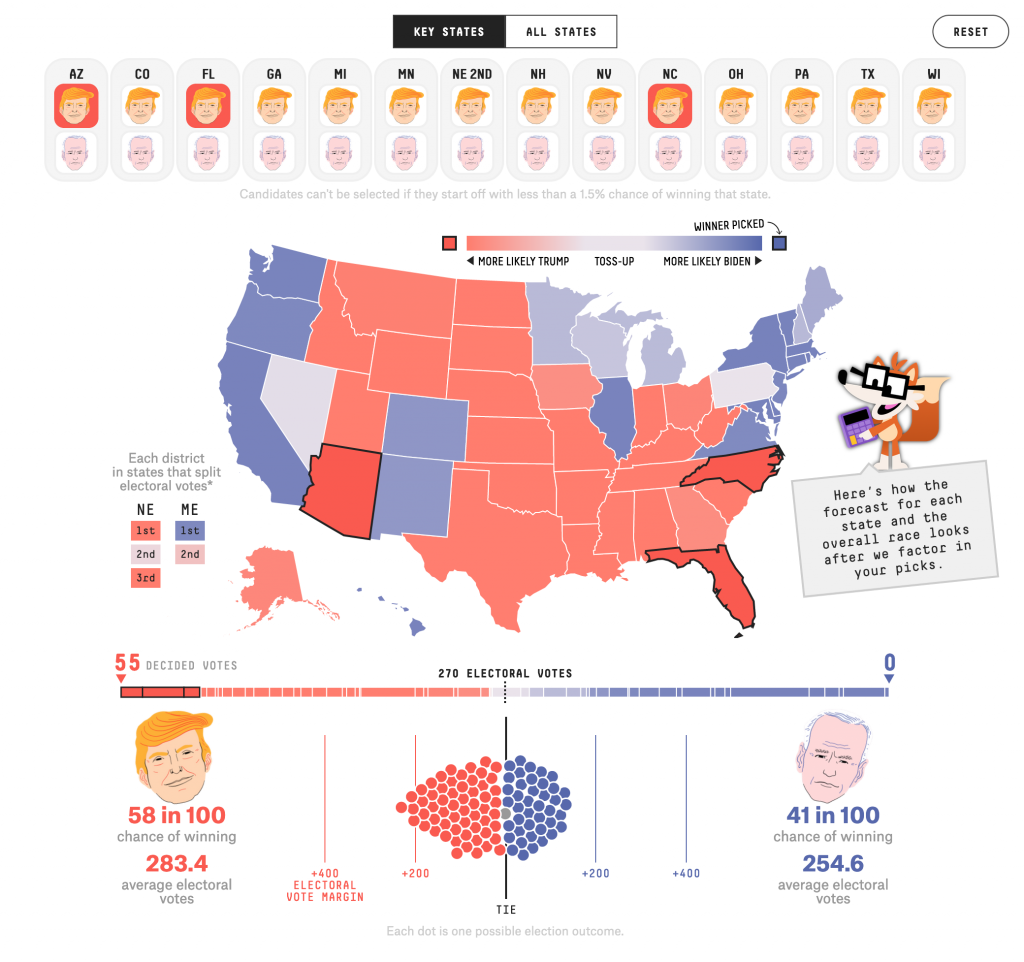

So what happens with this FiveThirtyEight model if we determine the winners of those three states? All three voted for Trump in 2016, so let’s say he wins them again next week.

We see that the states we’ve decided are now outlined in black. The remainder of the states have seen their colours change as their odds reflect the set electoral choice of our three states. We also now have a rest button that appears only once we’ve modified the map. I’m also thinking that I like FiveyFox, the site’s new mascot? He provides a succinct, plain language summary of what the user is looking at. At the bottom we see what the model projects if Arizona, Florida, and North Caroline vote for Trump. And in that scenario, Trump wins in 58 out of 100 elections, Biden in only 41. Still, it’s a fairly competitive election.

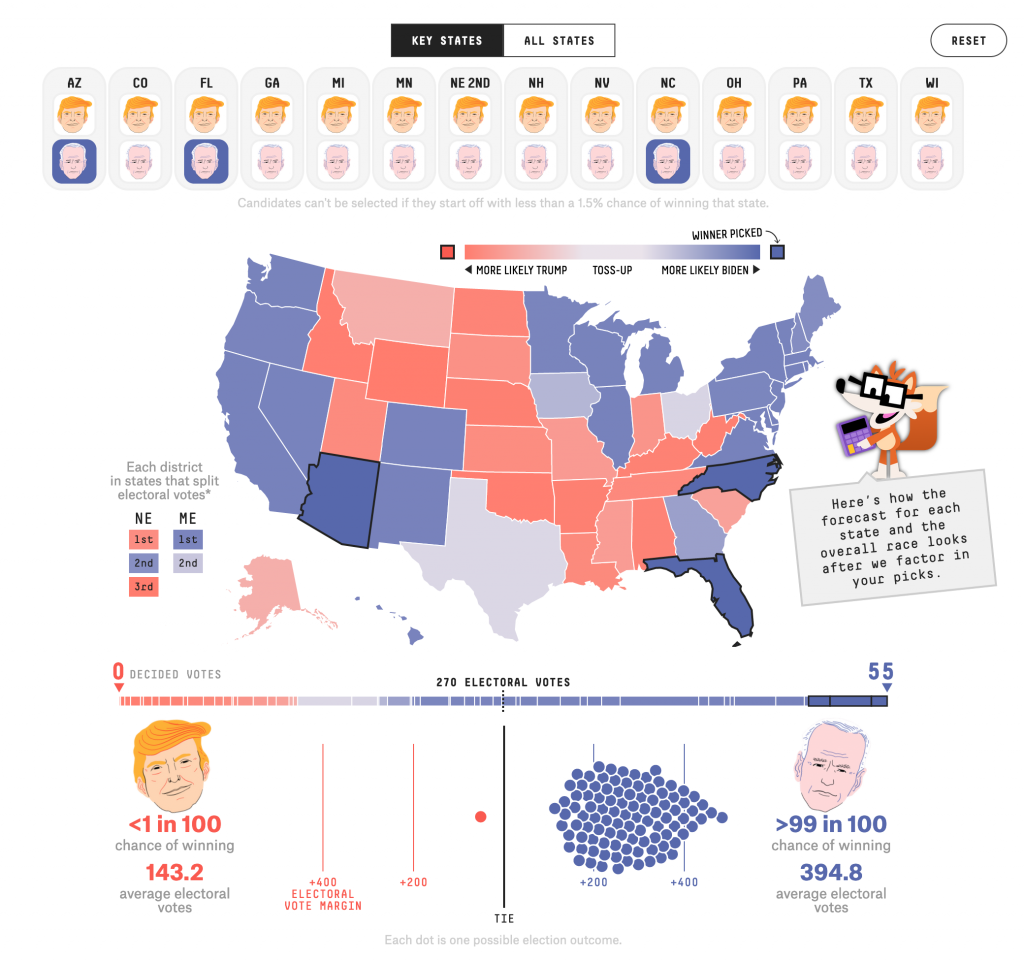

So what happens if by midnight we have results from those three states that Biden has managed to flip them? And as of Thursday morning, he’s leading very narrowly in the opinion polls.

Well, the interface hasn’t really changed. Though I should add below this screenshot there is a button to copy the link to this outcome to your clipboard if, like me, you want to share it with the world or my readers.

As to the results, if Biden wins those three states, Trump has less than a 1-in-100 chance of winning and Biden a greater than 99-in-100.

This is a really strong piece from FiveThirtyEight and it does a great job to show how states are subtly linked in terms of their likelihood to vote one way or the other.

Credit for the piece goes to Ryan Best, Jay Boice, Aaron Bycoffe and Nate Silver.