Tag: data visualisation

-

Turn Down the Heat

First, as we all should know, climate change is real. Now that does not mean that the temperature will always be warmer, it just means more extreme. So in winter we could have more severe cold temperatures and in hurricane season more powerful storms. But it does mean that in the summer we could have…

-

New Mexico Burns

Editor’s note: I was having some technical issues last week. This was supposed to post last week. Editor’s note two: This was supposed to go up on Monday. Still didn’t. Third time’s the charm? Yesterday I wrote about a piece from the New York Times that arrived on my doorstep Saturday morning. Well a few…

-

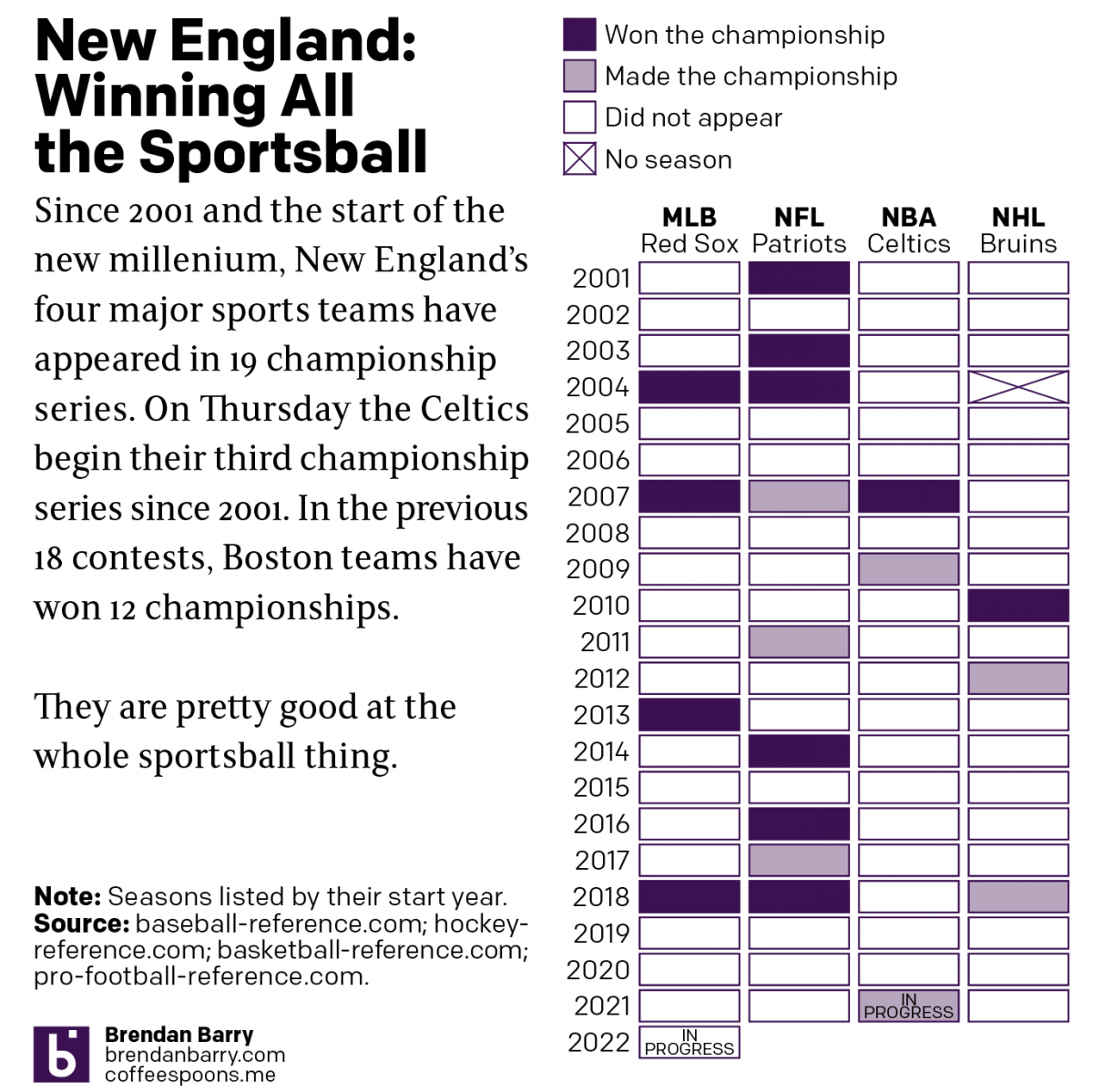

Boston: Sportstown of the 21st Century

Tonight the Boston Celtics play in Game 1 of the NBA Finals against the Golden State Warriors, one of the most dominant NBA teams over the last several years. But since the start of the new century and the new millennium, more broadly Boston’s four major sports teams have dominated the championship series of those…

-

Kids Do the Darnedest Things: But Really They Do

Remember how just last week I posted a graphic about the number of under-18 year olds killed by under-18 year olds? Well now we have an 18-year-old shooting up an elementary school killing 19 students and two teachers. Legally the alleged shooter, Salvador Ramos, is an adult given his age. But he was also a…

-

The Shrinking Colorado River

Last week the Washington Post published a nice long-form article about the troubles facing the Colorado River in the American and Mexican west. The Colorado is the river dammed by the Hoover and Glen Canyon Dams. It’s what flows through the Grand Canyon and provides water to the thirsty residents of the desert southwest. But…

-

Whilst We Wait for Roe…

to be overturned by the Supreme Court, as seems likely, states have been busy passing laws to both restrict and expand abortion access. This article from FiveThirtyEight describes the statutory activity with the use of a small multiple graphic I’ve screenshot below. Each little map represents an action that states could have taken recently, for…